While rents have been soaring for years in urban areas around the world, one Australian city has weathered the storm. What can the world learn from the experiences of Sydney?

One consequence of Covid has been plunging rents in cities across the world, as tenants flock out of city centres and the long-term rental market is flooded with former Airbnb properties. This has left tenants jubilant, and landlords panicked.

Sydney, Australia, is no different. But what is remarkable is that rents and house prices in Sydney were falling some time before Covid struck. From a peak of A$550 per week in 2015 (£310, US $420), the median unit rent had fallen a substantial 7.3% by December 2019. House prices fell from a median of A$1,075,000 in December 2017 to A$865,000 a year later. By contrast prices in London, UK, have been broadly stable since 2016 after almost two decades of meteoric growth. The cause of this was pretty simple. Sydney built more houses. But how it did it is the interesting part.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

For renters and those wanting to buy their first home, a drop in prices is an unmitigated boon. It means more people able to own their own home. It means people trading up into better quality housing for the same price, or living closer to where they want to be, reversing the “gentrification” trend that has pushed those on lower incomes further from employment opportunities. It means that landlords have to compete for tenants by managing the property well and keeping it in a good state of maintenance, a natural boost to the productive economy. It starts to reverse the enormous transfer of wealth from younger renters to older landlords. And it brings housing closer towards the standards of most other products and services – which have improved in quality and price drastically over the last century.

What happened, and can other cities across the world emulate it?

What makes a house price

To understand, we should first look at the factors that determine house prices. These fall into two categories – supply-side, and demand-side. The supply of housing is quite simply the units available on the market at any one time, both existing units and new builds. The demand side aggregates peoples’ willingness and ability to pay for housing, from the number and size of households and the income they have and want to spend on housing, to the availability and cost of credit and speculative demand. Change any one of these variables, and with the others held equal, you will expect house prices to change in response – higher demand or lower supply leading to higher prices, and vice versa.

Some of the factors determining prices, like interest rates (which are at historic lows across the world), speculation, population growth and income growth are international, or at least widely shared amongst cities. Most of these have served to increase house price or rent inflation in cities across the world by adding to demand, either by making it cheaper to borrow more for a mortgage, by making rental income relatively attractive compared to other investments, or increasing the number of people or the money they have to spend on housing.

In most major cities, these factors have interacted with a relatively fixed stock of housing, leading to higher (and often consistently rising) prices for renting and for buying houses outright.

Sydney has also had falling interest rates, a rising population and richer people. What it has done differently is to look at the supply side – in Sydney, in recent years, the housing stock has not been held constant. Across the Greater Sydney Region, almost 182,000 homes were built in the last five financial years: an average of 36,000 per year, a drastic increase on the period 2000-14 when they averaged under 20,000. This works out at around 70 homes per 10,000 residents each year. This is substantial compared to other cities around the world that are famously struggling with house price inflation. In comparison, San Francisco, in what was a bumper year with 68% more new homes in 2019 compared to the 10-year average, still only built 53 new units per 10,000 residents; London 40 per 10,000, and New York City managed just 29 per 10,000 residents in 2019.

Planning to win

The New South Wales (NSW) regional government had identified a failure to build feeding into worsening affordability problems since the late 1990s. In 2015, it set up an independent agency, the Greater Sydney Commission, to lead on land use issues and prepare district and regional plans. The Commission set and distributed much higher housing targets amongst the councils across Greater Sydney.

These targets were, and remain, controversial. Much like cities across the developed world, local opposition to new development is vocal, as laughable as assertions that there is “no demand” for homes in one of the most desirable suburbs may be. Opposition politicians have accordingly seized the political opportunity and claimed that areas of Sydney are being “clobbered” by over-development. Local councils have also pushed back.

The optimal approach may have been to allocate higher targets to areas with higher prices, or more precisely, larger gaps between build costs and prices, as those gaps are the key indicator of substantial unmet demand. In fact the targets – and the “priority growth” areas – were disproportionately assigned to the less well off neighbourhoods. Relatively poor Parramatta, for instance, received a 0-5 year target of 21,650 homes – or a substantial 168 homes per 10,000 residents, over five years. Woollahra, Waverley, and Randwick – the richest suburbs in the country – collectively received a target of 3800 dwellings, or 38 per 10,000. This follows a pattern observed across supply-constrained cities, that wealthier areas tend to be better organised and able to resist new development (and perhaps tellingly, have the greater financial incentive to keep their asset prices inflated).

In order to implement these targets, councils were required to update their local plans accordingly and “priority councils” – those with the largest targets – received extra funding to do so. The NSW Department of Planning and Environment issued centrally-prepared guidelines to help councils accelerate rezoning applications, expanded “complying development” (a fast-track approval process for straightforward developments) to denser types of building, and simplified greenfield release. It depoliticised the planning process by removing councillors and developers from planning panels, instead appointing independent experts.

In fact, what is striking is that these are just a few of the many supply-side actions taken by the NSW government to strip away restrictions on house building and issue more building permits. Housing supply was substantially improved in Sydney, largely as a result of liberalising planning reforms; but it suggested that even an incremental removal of the myriad barriers that planning presents can be effective, without having to necessarily commit to politically difficult whole-system reform.

Are permissions enough?

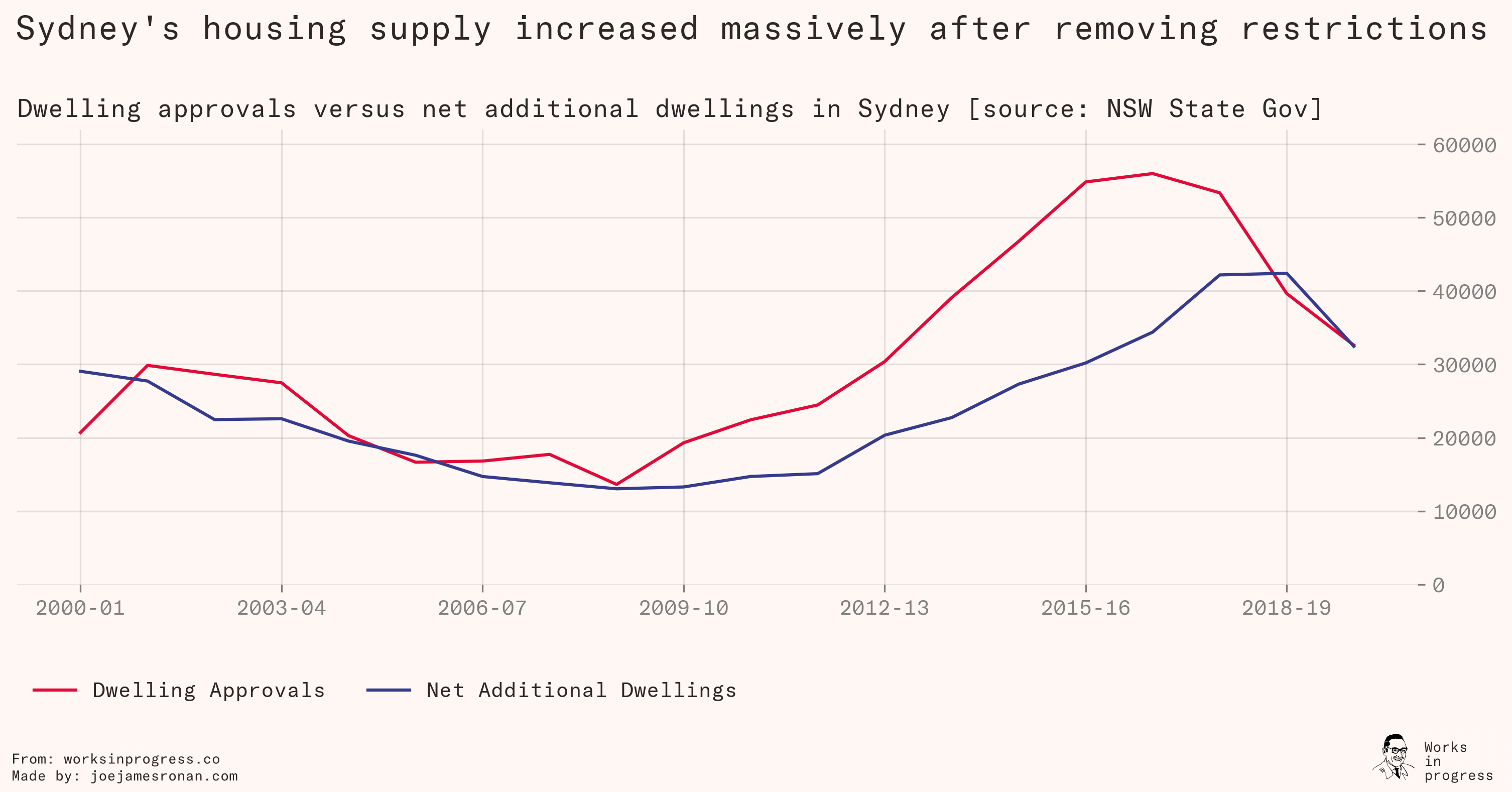

There is a common claim in British planning discourse that releasing more permissions cannot solve housing shortages, since once the developers hold the permission, they have little incentive to build quickly. The argument goes that developers only use up a limited number of their permissions each year, drip-feeding new homes at a rate that allows them to sell as dearly as possible. It follows that more liberal supplies of permissions will not lead to more housing. Sydney is a clear counterexample to this narrative, which in any case was always rather parochial, failing to check whether other housing markets had similar “land banking” problems as Britain. Figure 1 shows a clear and very strong relationship between dwelling approvals (planning permissions) and new dwellings, allowing for a lag for development to take place. In other words, if you allow more building, there will be more building.

The figure also shows that not all additional permissions feed into new supply: the supply peak is about 13,500 units lower than the permissions peak. This observation is often used to demonstrate that planning is not a barrier for housing supply. The short answer to this is that it does not matter. There is no logical requirement for a 1:1 permission/development ratio, as long as more permissions result in some increase in new builds (as they clearly do). If only one home were built for every two additional permissions, this would indicate that planners should double permissions, not consider their work done. Developments can lapse for any number of reasons, including lapses – such as the collapse of financing arrangements – caused by delays in the permission process itself.

From permissions to affordability

Sydney’s experience demonstrates that liberalised planning leads to more homes. But do more homes lead to better affordability? To economists, the fact that building more homes reduces rents is so obvious, it is almost a truism. The theory and the empirical evidence are both clear. But pro-housing groups across the world regularly encounter opposing views – that “luxury [market] developments” actually increase prices in certain areas; that developing new market homes will not reduce rents at the cheaper end of the market; or that while new development may reduce prices, it is not possible to build enough to bring down prices materially.

The first of these arguments is easily dismissed as a simple confusion of cause and effect. Prices rise where supply does not meet demand. Developers will then want to build there because rising prices offer the greatest opportunity for profit. These developers do not cause house price rises any more than a burger stand being set up in a football stadium causes hungry football fans: they are responding to a need, and in fact reducing that unmet need. But if you have a licensing system that restricts the number of burger stands, you’re going to have hungry football fans anyway.

The second is demonstrated false by Sydney’s experience. Although most of the new homes were not what city planners call “Affordable Housing”, the new construction has nonetheless reduced housing costs at the bottom of the market too. This happens because of a process called filtering. Wealthier residents swap up into newly built housing, which tends to be of higher quality than existing aged stock. This leads to more units being on the market at once, reduces demand (from the household and their higher income) and therefore prices on cheaper units. A person paying A$20,000 a year on rent isn’t competing for a property with someone who can pay A$100,000. But they may compete with someone who pays $25,000, who competes with someone who can pay $30,000, and so on, all the way up the income scale. When there are newer units available, landlords have to compete to attract tenants to the older units – either by dropping the rent or by offering a better maintained property. Anecdotally, Sydney renters have started to see the better management and repairs that come with a falling market.

The final argument, that it’s not feasible to build enough houses to significantly dent housing costs, is generally trickier to counter, not least because the various factors affecting housing costs make it hard to quantify the impact of one variable, at least without some serious (and difficult-to-communicate) statistical analysis. The time lag between giving permission for homes and those homes appearing in the available supply also complicates matters. There are a number of places around the world that have successfully constrained house price inflation. In Tokyo, prices have been flat for two decades. In Houston, the average home costs 190,000 USD, just four fifths of the national average despite being a major city. But Sydney’s experience is an example that building homes doesn’t just prevent inflation: you can actually reverse it, in a relatively short period, with an achievable increase in supply.

Not everyone is happy to see lower prices

Given Sydney’s apparent success in pushing back against a tide of rising rents across the developed world, you would be forgiven for thinking that local policy-makers are patting themselves on the back. But in fact a number of councils have pushed back against the higher targets, calling for downwards revisions. Mayor Jennifer Anderson of Ku-ring-gai, one of the wealthiest council areas in Australia, has been a particularly vocal critic, seizing on the NSW Government admission that the targets were not legal requirements to amend the council’s draft housing strategy. This is all the more remarkable given the very low target Ku-ring-gai was set: just 3600 homes over six to 10 years, or about 20 homes per 10,000 residents per year – less than an eighth of Parramatta’s rate.

So while Sydney’s experience does suggest that a sufficiently motivated regional or central authority can push changes past recalcitrant councils, they still have to do this against the familiar backlash from local politicians. The lower targets given to areas like Ku-ring-gai – where people want to live most and where an efficient, demand-based allocation system would prioritise new homes – are evidence of this happening preemptively, even before the local plan-making stage.

It raises the question of how sustainable these top-down targets are over the long term. It might be easy to push through new developments in relatively poor Parramatta, but building where homes are most wanted is less achievable because of the influential vested interests established there already. England discovered this recently when the government established new housing targets and then swiftly “rebalanced” them away from wealthy enclaves around cities. Of course, this is not to say we should not have high targets in poorer areas: it is poorer people who are set to benefit most from improved housing supply. But there is clearly a huge societal cost in letting wealthier areas get away with not building. That this NIMBY problem exists the world over, and has yet to be successfully reversed in areas where objectors to development have substantial political sway, presents a tactical challenge for those that advocate more house building. Proposals by London YIMBY to offer residents street votes on “upzoning” – thereby offering a financial incentive to support housebuilding in their area – could be the key to breaking this barrier.

Looking back at news from a few years ago also offers an interesting insight for those interested in housing affordability. A 2016 article in the Sydney Morning Herald lamented that a “record number of homes [have been] built in Sydney, but it’s still unaffordable”. Commentators lined up to say that increased supply “hasn’t generated any significant benefit” and that it “isn’t going to relieve the affordability crisis”. Of course, these commentators were proven wrong very shortly afterwards by a rapid and significant fall in rents that made quite a difference to rental affordability. No doubt they issued their mea culpas accordingly, and that commentators the world over will make note of this lesson.