Washington, DC, has avoided the worst price rises that have plagued many other growing American cities. Arlington’s transit-oriented development might be the reason.

Across much of the Western world, the price of housing far exceeds the cost of building it. Many regions are suffering from increasingly severe housing supply challenges, with the typical renter spending a quarter more on housing today than in 1980. The Washington, DC, region, led by Arlington, Virginia – just over the Potomac river – has shown a way to avoid the worst of the crisis. By concentrating apartments around transit, buying the most-affected locals in financially, and using the revenues to balance the budget, it has been able to permit more apartments than many of its peer regions over the past 50 years. This is a model other American cities could learn from.

In part, today’s housing affordability problems are due to economic and population shifts. As people move toward centers of the information economy and away from centers of manufacturing, they compete for housing. In general, people moving to these economies earn higher incomes than other residents, and bid up the price of limited real estate. In a particularly important case, the San Francisco Bay Area, house prices grew 932 percent in the past 40 years while overall consumer prices increased by 329 percent.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Overall the US has an abundance of land. Across the Sun Belt, US cities like Dallas and Atlanta have maintained relatively attainable housing by sprawling out in all directions. But many of the country’s highest-income cities face geographic constraints on new greenfield development plus regulations preventing homebuilders from building more densely in developed areas when demand increases. In these places, housing is unaffordable to many and becoming more so.

Four US metropolitan areas in particular – Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Boston – have become increasingly expensive, thereby pushing out low- and middle-income families as higher-income in-migrants outbid them for a stagnant supply of housing. Two other ‘superstar regions’ with high productivity and high average incomes – DC and Seattle – are doing a better job of accommodating new demand for housing with new housing construction. Relative to the other four superstar cities, they are losing domestic residents at much lower rates. DC, Seattle, and some other growing cities across the country are suffering from their own housing shortages, but not on the same scale as those places with the most severe impediments to housing construction.

DC’s relative success can be traced to a few decisions made decades ago. In the 1970s, policymakers in Arlington County made a decision to adopt what’s known as ‘transit-oriented development planning’ ahead of the opening of DC’s Metro Orange Line, which runs between Arlington and Prince George County, Maryland (via DC). Arlington policymakers identified that zoning for apartment construction in commercial areas could bring in property taxes and help balance the budget without the level of controversy of changing zoning in existing residential areas. Some nearby jurisdictions followed suit, learning from Arlington’s example, helping the DC region stay more affordable than the country’s other superstar cities.

A brief history of transit-oriented development in Arlington

Most suburban localities in the US spent the past century shutting down opportunities for apartment construction. By 1931, just 15 years after the country’s first zoning ordinance was adopted, two-thirds of Americans lived in a zoned municipality. By the 1970s, fueled by the growing environmental movement, some suburban localities had gone so far as to adopt explicit growth controls, capping the number of housing units they would permit annually. Arlington County, VA, went a starkly different direction. Like most suburban localities, Arlington’s first 1930 zoning ordinance restricted development on the majority of its land to single-family development with lot-size requirements of 5,000 square feet or more. However, beginning in the 1960s, Arlington deviated from other suburbs of coastal cities and began creating new opportunities for apartment construction.

Much of Arlington was originally developed as a streetcar suburb of the District in the first half of the 20th century. Clarendon, the county’s ‘downtown’, sits at the intersection of three major arterial roads which were historically important trolley and bus lines. In 1957, the County Office of Planning identified a fiscal imbalance, following a period of rapid population growth. The county was not collecting enough tax revenue from its single-family housing to cover rising public expenditures. The report found that households living in apartments contributed 25 percent of the county’s revenues and required 21 percent of its expenditures, while people living in single-family housing contributed 48 percent of county revenues and required 68 percent of expenditures, with commercial development making up the balance of each.

This finding – at odds with the conventional wisdom of the time – indicated that allowing more apartment construction could allow the county to avoid a tax hike for single-family homeowners. The report paved the way for a 1962 rezoning that permitted high-rise office and residential development, particularly along the arterial roads that meet in Clarendon. As a result of this policy change, Arlington, a small and entirely built-up county with 0.5 percent of the DC region’s land area, has permitted more than 5 percent of the region’s housing units built over the past 20 years.

Further changes came with planning for the region’s Metrorail system later in the 1960s, including the Orange Line which would cross the north half of the county. While the transit authority initially proposed an above-ground line using the existing right-of-way along the I-66 highway, county officials successfully lobbied for an underground line that would serve the existing commercial centers in the Rosslyn, Court House, Clarendon, Virginia Square and Ballston neighborhoods.

Planners engaged residents and developed a ‘bull’s eye’ plan for permitting dense development around these five stations, illustrated below. The quarter mile of land closest to the stations was intended for the most density. Today, several buildings stretching over 20 stories stand within these narrow radiuses. The exact density permitted in the county’s transit corridors isn’t spelled out in its zoning ordinance because projects may purchase transferable development rights from nearby property owners or earn bonus density for providing income-restricted housing or other benefits that lead the County Board to approve greater density than is permitted by-right.

In the decades since, the county has implemented new ‘sector plans’ continuing to create more opportunities for development around these five stations as well as around two stations on Metro’s Blue Line and along an east-west bus corridor in South Arlington. The maps below show the most recent 20 years of redevelopment and increasing population density that this history of planning for apartments has facilitated.

Development along the Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor is visible (most strikingly where I live, in Ballston) as is development along the other transit corridors. In the 1970 Census, ahead of the Orange Line’s inauguration, the county’s housing stock included about 30,000 detached single-family houses, a number that has remained steady in the decades since. But the stock of other types of housing has more than doubled from about 41,000 units to nearly 88,000 units. This infill apartment construction has allowed the county’s population to increase by 60,000 residents in this 50-year period – without expanding the area developed at all.

Today, much of Orange Line Arlington is surrounded with high-rise residential and office towers, but this transformation took time to emerge. In 1980, a Washington Post article bemoaned the difficulty of redevelopment in Clarendon, ‘a patchwork quilt’ of small parcels, many of them with long commercial leases. By the end of that decade, a large office building would flank the south side of the Metro station. Then, finally, in 2010, the entire block east of the Metro would be redeveloped with an award-winning Art Deco-influenced office, residential, and retail project. As shown below, the building incorporates a two-story original Art Deco building.

Emily Hamilton, private collection

A newer Art Deco-style apartment building is pictured below. It replaced a car dealership at the western end of the corridor.

Emily Hamilton, private collection.

Like every locality, some of Arlington’s commercial developments became decrepit over time or are no longer the best use of their land. But the county’s zoning makes it possible to replace buildings in decline with more productive ones. For example, Arlington had a dead mall that has received an extreme makeover. It was the country’s first to have a multistory parking deck, but was suffering from high vacancy when a renovation plan was approved in 2015. The new mall includes many food- and experience-focused vendors – things customers can’t buy online – as well as 300 apartments. Its revitalization contrasts with malls like Hilltop Horizon in the Bay Area, where proposals for mixed-use redevelopment have yet to be approved, allowing a near-vacant property to languish for years.

One argument against planning for apartments in limited areas near transit is that it can mean only building them on the wide arterial streets that tend to accompany mass transit, shutting out apartments from quieter streets that are safer for pedestrians and where air is cleaner. In Arlington, the leafiest and quietest parts of the county remain reserved for single-family zoning, but the bullseye approach to upzoning means that apartments are built on both arterials and relatively quiet, narrow streets near Metro stations as pictured below in the Courthouse neighborhood.

Emily Hamilton, private collection.

Arlington’s planning for the Orange Line is in line with our best traditions. Historically, transit was planned jointly with housing and other development. When the transit made new locations more convenient, it increased the value of the land there. The railway or streetcar company could thus profit, paying for the transit investment. This is still how some transit is funded in countries like Japan.

Arlington’s approach is quite different from most of the rest of the country. To take one example, zoning around the Bayfair station on Bay Area Rapid Transit in San Leandro, California has locked in low-density commercial and residential development as shown below.

Image used with permission from Google Maps, Maxar Technologies, New York GIS and USDA/FPAC/GEO.

Even in Arlington, while land that was developed with commercial uses near Metro was generally upzoned according to the bullseye plan, the county carved out some single-family neighborhoods where residents didn’t want to see land-use changes from upzoning. Today, there are single-family houses just one tenth of a mile from the Metro in Clarendon, because their zoning prevents denser redevelopment. And the plan wasn’t carried out universally: the area around the county’s westernmost Metro station, East Falls Church, is zoned exclusively for low-density development.

Largely this is due to reluctance among local homeowners. But Arlington planners have been careful to work with the grain of homeowner interests where possible. For example, transit-oriented development zoning permitted the development of an outdoor mall, apartments, and townhouses at a site east of the Clarendon Metro, adjacent to a neighborhood of single-family houses. The county built a park between the new construction and older houses. A documentary about urban planning in Arlington describes the park as a ‘trade’ with the homeowners, in exchange for their acceptance of new construction nearby.

In one case, the owners of about 20 single-family houses in Courthouse united to get their land included in the bull’s eye plan. In 1977, these homeowners sold to an office developer for about three times their properties’ value as houses prior to the Metro station opening in 1979. A 1980 article from the Washington Post reported that prices for single-family houses in Ballston doubled following the opening of its Metro station and the associated zoning that permitted townhouse redevelopment.

In these cases, residents saw that new transit, combined with the opportunity to change their zoning to permit denser development, gave them an opportunity for a large windfall. But most of the county’s homeowners have not sought to upzone their low-density neighborhoods. Given the potential for profit, this is perplexing.

Why hasn’t this happened everywhere? Some of the explanation is extreme risk aversion among homeowners. Zoning has complicated effects on property values. Zoning that takes away the right to develop densely in job centers depresses land values there, pushing up land values at the region’s outskirts. Zoning that limits housing construction also increases the value of all existing housing. Homeowners have highly imperfect information about how a change in zoning will affect their land value, house value and total property value. Because many homeowners hold a large share of their wealth in their houses, they often choose to fight any land use change with even a small chance of reducing their property value.

By generally limiting upzoning to areas without homeowners, unless those homeowners have consented, Arlington has permitted much more development than other expensive cities without huge blowback from homeowners.

The politics of transit-oriented development in the broader DC region

Within the DC region, Arlington has not been alone in permitting new apartment construction on commercial land along its transit lines. In 2000, Montgomery County, Maryland, which borders DC to the north, adopted a plan for dense, mixed-use redevelopment in downtown Silver Spring, its most urbanized area. As in Arlington, upzoning in Silver Spring was intended to improve the county’s balance sheet. And it worked: between 2000 and 2004, property tax revenues in Silver Spring increased by 30 percent. More recently, policymakers there have implemented redevelopment planning in Bethesda and White Flint (recently rechristened ‘North Bethesda’), as well.

The District itself has permitted extensive redevelopment of formerly industrial neighborhoods when they received new Metro stations, including Navy Yard and NoMA. In the years since the 2010 financial crisis, DC has permitted thousands of apartments each year, a high rate compared to peer cities. As in Arlington, they’ve primarily been permitted on land that previously housed industrial or low-value commercial development where there are few or no existing residents to oppose new construction.

In 2010, policymakers in Fairfax County, Arlington’s neighbor to the west, adopted a major redevelopment plan for Tysons, a four-square-mile area, ahead of the construction of the Silver Line. Tysons is famous for traffic congestion, two high-end shopping malls, and many suburban office parks. When the plan was adopted, Tysons had fewer than 10,000 homes, and about half of those were rental units. Office tenants were leaving Tysons for more vibrant neighborhoods that their workers preferred in DC and Arlington, leaving vacant buildings behind. As in Arlington, Fairfax policymakers saw redevelopment in Tysons as a way to shore up their tax base and avoid the need to raise property tax rates on single-family homeowners. While property taxes are a crucial revenue source for all localities in the DC region, Virginia localities rely more heavily on property tax revenues than Montgomery County or DC because they do not have local income taxes, which Virginia law prohibits.

Fairfax County planners repeatedly cited the vibrant Rosslyn-Ballston Corridor as their inspiration for redevelopment. The extent to which planning in Tysons will achieve its stated walkability goals is debatable, but redevelopment planning has facilitated the construction of 4,500 new apartments with thousands more in the development pipeline. All of this apartment construction is taking place in one of the country’s highest-income suburban counties. Many of Fairfax County’s peers in California, Massachusetts, and New York are permitting virtually no apartment construction. For example, between 2000 and 2020, the stock of apartments in Marin County, just north of San Francisco, didn’t increase at all. Long Island didn’t do much better, with its supply of housing other than detached single-family housing increasing by about seven percent in those two decades. By contrast, Fairfax County’s increased by about one-quarter.

How was all of this new construction politically feasible? The chair of a task force appointed to guide redevelopment planning pointed out that Tysons wasn’t in any homeowner’s backyard. Freeways and arterial roads separated it from nearby neighborhoods, likely dampening resistance to new housing being built around the new Silver Line stations even more than in Arlington.

As well as limiting the impact of construction, Fairfax authorities sought to make Tysons a boon for homeowners in other parts of the county by implementing special transportation fees for development. In addition to the county’s standard property taxes, owners in Tysons also have to pay an additional 0.05 percent property tax to support public services there. In spite of these costs, development continues to proceed in Tysons because of the value that upzoning there unlocked.

Untangling the relationship between the amount and type of housing that localities permit and their finances is complicated and depends on many interrelated factors, both within and outside policymakers’ control. But we can look to an example from Bergen County, NJ for some evidence of how development relates to property taxes. One locality, Palisades Park, allows two-family development – what Brits would call semi-detached houses – while its neighbors zoning ordinances either ban two-family construction or make it relatively unattractive.

Even though its zoning allowed more, Palisades Park was initially developed as primarily detached single-family houses. Then, starting in the 1990s, Palisades Park began seeing duplex redevelopment due to increasing land prices in the New York City region. Between 1997 and 2018, Palisades Park went from having average property tax rates among the six jurisdictions surrounding it to the lowest. Palisades Park policymakers implemented a one year moratorium on duplex construction in 1996, shortly after their construction started becoming commonplace. The moratorium resulted in lower values for homeowners due to the reduced option value of their property. In turn, it required policymakers to increase property tax rates. They reversed the moratorium the following year.

In addition to demonstrating the fiscal benefits of permitting infill construction, Arlington has provided nearby areas with a nearby example of dense development that has improved walkability by making it possible for restaurants and grocery stores to open close to offices which abut single-family neighborhoods. Traffic counts on many Arlington thoroughfares have declined since the 1990s, in part because development has been concentrated in places that are walkable to job centers and with Metro access to many others.

Contrary to some of the received wisdom on high-density residential construction in the U.S, Arlington has a highly-rated school district (one school ranking organization ranks it second in Virginia, behind only the city of Falls Church, Arlington’s neighbor to the west with fewer than 15,000 people) and high and rising property values (with a median house value about 2.3 times the US median). The county has an extensive, high-quality network of parks. A former county manager speculated that without the county’s planning for high-rise construction, single-family homeowners’ property taxes would have to be 10 percent to 30 percent higher to pay for them.

Initiating a trend of pro-housing reforms in Arlington was easier than it might have been elsewhere. Arlington has a County Board whose five members are all elected at-large – meaning they all represent county residents as a whole, rather than individual wards within the county. At-large representation avoids the potential for systems of aldermanic privilege, in which council members agree not to approve new housing if the member whose district the proposed project is in votes against it. Localities tend to permit housing at lower rates if they switch from a council of at-large representatives to district representation.

The Arlington model has created a path-dependent acceptance of apartment construction in transit corridors, setting the region on a different course for housing construction and affordability relative to most comparable regions.

DC’s relative housing abundance

By planning for apartments in some of the commercial areas where it’s politically easiest to allow it, the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Statistical Area has facilitated more housing construction than most other ‘superstar’ regions in the US. It has seen more than twice the growth in its housing stock over the past 20 years of the Bay Area. In economics terms, the DC region has more elastic housing supply compared to most of its peers.

Supply elasticity – the extent to which supply increases in response to higher prices – is calculated by looking at the percentage change in the quantity of a good divided by the percentage change in its price over a given time period. If a good has a highly elastic supply, an increase in demand will lead to a large increase in the quantity produced and a small increase in its price. In contrast, when demand for housing increases in a place where rules prevent construction, the supply of housing increases very little and its price rises significantly. The table below shows US superstar cities’ construction rates, price changes, and housing-supply elasticities over the past two decades.

Housing construction and supply elasticities in superstar metropolitan statistical areas, 2000 to 2020

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | Percent Change in Total Housing Units | Percent Change in Multifamily Housing Units | Percent Change in Nominal Median House Price | Housing Supply Elasticity |

| Los Angeles | 9.91% | 13.3% | 193% | 0.0514 |

| San Francisco | 12.7% | 13.5% | 213% | 0.0596 |

| New York | 9.4% | 10.5% | 114% | 0.0822 |

| Boston | 12.6% | 11.1% | 114% | 0.111 |

| Washington, DC | 24.6% | 27.4% | 128% | 0.192 |

| Seattle | 28.9% | 36.0% | 141% | 0.201 |

Among superstar metros, only Seattle has achieved a housing supply elasticity greater than DC’s, and then only slightly. Like DC, Seattle has pursued a transit-oriented development strategy with its Urban Villages plan, which has zoned for large apartment buildings in about two dozen neighborhoods throughout the city. Some of Seattle’s suburbs, including Bellevue, have also, like Arlington, been more open to apartment construction relative to the suburban jurisdictions surrounding other superstar principal cities.

Between 2012 and 2018, rents in DC actually rose slower than inflation. Virginia Beach, VA, was the only other large metropolitan area in the country for which this was true.

The limits of transit-oriented development alone

Despite this success, there is a lot more the DC region could do to allow more, lower-cost housing. Most neighborhoods across the region have large minimum lot sizes, wide streets and pavements, deep setbacks, and low storey limits leading to densities of 4,000 people per square kilometer or less, densities seen in few urban areas outside of the United States. Arlington’s overall population density is just 3,500 people per square kilometer, with only small parts of its land area achieving much higher densities.

By zoning only a small amount of their land for apartment development, jurisdictions in the DC and Seattle regions ensure that much of the apartment housing that is built will be in towers that maximize allowable floor area. This approach cuts low-rise apartments out of the market, which are much cheaper to build on a per square foot basis. It also largely prevents new townhomes, the relatively dense urban form which makes up much of historic DC. A regulatory regime that leads to high-rise construction alone sets a limit on the affordability of new construction and housing supply because housing will cease to be built if rents fall enough not to cover the high costs of high-rises.

Arlington County policymakers have adopted reforms to allow single-family homeowners to build accessory dwelling units, but few have been built in part due to remaining regulatory barriers, including a requirement that the property owner must live on site in order for the accessory dwelling unit (ADU) to be rented out. This restriction has proven to make it difficult to finance ADUs and reduces the value that they contribute to a property.

Just this spring, the County Board passed a new ordinance legalizing ‘missing middle’ housing – up to six units on a lot – where only detached single-family zoning was allowed previously. While this reform will only deliver a small amount of new housing relative to what’s been built in the county’s transit corridors, it’s the next step in maintaining opportunities to grow. It will also improve affordability and consumer choice for households with children in particular, since small units in highrises may not meet their needs.

Learning from transit-oriented development in the DC region

Even though upzoning for apartments near transit stations typically changes development rules on a small portion of a locality’s land, it can deliver a serious amount of housing. The state of California has earned well-deserved accolades for a bold accessory dwelling unit policy that has created opportunities for homeowners across the state to build rental units on land otherwise restricted to single-family development.

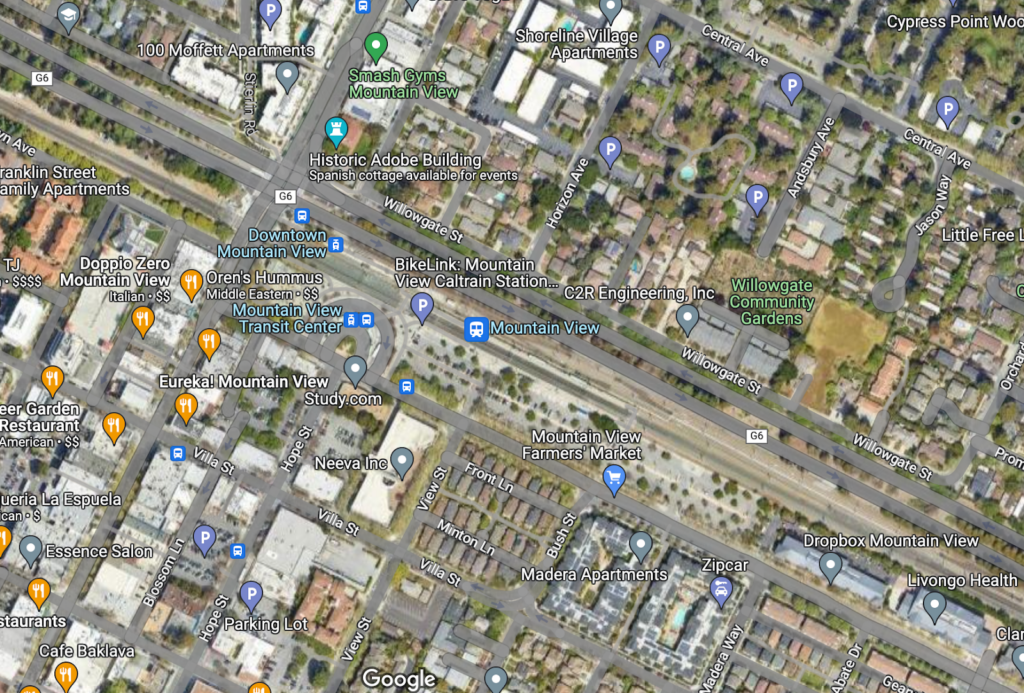

The city of Los Angeles has had particularly notable success with ADU permitting, and there the rate is a little over 1 per 1,000 residents per year. During this time period, Arlington permitted nearly 7 multifamily units per 1,000 residents annually on average. Following the Arlington model of permitting high-rise residential to replace the low-value commercial development next to Caltrain’s Palo Alto or Mountain View stations, or Metro North’s Irvington or Ossining in New York should be a planning no-brainer.

Here, the Irvington station on the New York region’s Metro-North is adjacent to low-value commercial development. Below, similar development patterns are seen at 1) the Ossining station on Metro-North, 2) the Palo Alto station on Caltrain, and 3) the Mountain View station on Caltrain. These contrast with the Arlington approach of permitting dense, mixed-use development near transit stops.

The Arlington experience shows that carefully planned densification can bring benefits to homeowners by helping balance local budgets and supporting vibrant retail and commercial centers. Current land use policies in many of the country’s most productive regions are pushing residents out and creating astronomical housing costs for those who stay. Following the DC region’s model for creating opportunities to build many more apartments on just the small amount of land near transit stations could go a long way toward allowing more people to live where their best opportunities are located.