We’ve learnt to see the world through the eyes of our prey. All the better to eat them with.

‘Can’t you feel it?’

‘Feel what?’ I asked

‘How we are turning into greedy predators, just like wolves. We have this need to kill more and more. Even if we had two hundred sables we wouldn’t feel satisfied, would we? Just like the devil, you see.’ He paused for a while. Then he added, ‘I suggest we calm down and stop hunting for a week or so.’

– Rane Willerslev, Soul Hunters

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

If you ran out of food, would you hesitate to eat your dog? If stranded on an island, have you put any thought into how you would carve up the family cat?

What is it that separates these animals from the ones you can encounter on a farm? If this question is difficult to answer, then you have a certain general unease about killing and eating animals. Why, then, would you choose to eat meat?

An ongoing question in the psychology of empathy is why, if people love animals, we nevertheless choose to kill and eat them. This question, known as the Meat Paradox, is one whose answer could help to resolve many of the modern contradictions we find between vegans and meat eaters alike. For instance, many ethical vegetarians cannot seem to understand how meat eaters can make the conscious decision to end an animal’s life when they will seemingly extend empathy to other animals in other situations.

Many meat eaters cannot understand the unnatural character of the vegetarian position: We evolved to eat meat, and only in recent years is it the case that society has deemed it a problem. Only in recent years has our modern isolation from the natural state of affairs, when we had to hunt and kill our food, created an empathy for animals where there was not one before.

But is this Meat Paradox an actual paradox? Why would we have empathy for our prey?

One potential explanation is that it could be an evolutionary spandrel, or by-product, due to our advanced ability to empathize with one another. Like lions, chimpanzees, and other predators red in tooth and claw, we were always supposed to be cold-blooded predators who saw our food as food and nothing else. But perhaps when we evolved familial and tribal bonds, and eventually national and international bonds, not to mention bonds with our useful pets like dogs, the cognitive mechanisms weren’t perfectly specific, and have attached more broadly to nonhuman agents.

I wish to advance an alternative case. What if our empathy allows us to think like, act like, and even kill our prey? Without a time machine, answering this question completely conclusively is impossible. Fortunately, what we do have is the ethnographic and cross-cultural record where we can ask: In environments and ecological situations similar to the ones we evolved in, how do humans think about their prey? Do they think like them, and do they feel bad for the animals they kill?

People who are familiar with hunting tactics in the West understand how deceiving other animals works. My great-great-uncle taught my father how to hunt rabbits when he was a child. If a rabbit tried to run away, you could simply whistle – the rabbit would believe you were a hawk and stop dead in its tracks. To this day we use hunting lures, duck decoys, and imitated animal calls to lure in our prey, as we see in one of the 2010s’ most powerful television shows, A&E’s Duck Dynasty, which follows a family with a $400 million fortune originally made by producing duck- and turkey-calling implements from their dilapidated boat home in Louisiana.

There is evidence that these imitation practices are used around the world. As a master’s student, my colleague Michael Alvard told me a story about his time with the Piro hunter-gatherers from the Peruvian Amazon.

A tribesman asked him if he would like to see how a single hunter could take out a flock of birds with a single blowgun. Not believing it, Alvard went with the hunter to watch the process. Approaching the flock of birds, the hunter fired a dart, injuring one, which fell to the forest floor. Startled, the flock disappeared. But still alive, the bird began to signal to its flock it was in trouble. Curious about their friend, the birds would return, the hunter would kill another, and the birds would fly off, only to return again to the calls of their friend. The hunter did this until the entire flock was killed.

Peering into the ethnographic record, such stories are not uncommon. As my colleagues Will Buckner, Melina Sarian, and Jeff Winking, and I have found in our own research, the methods humans around the world use to deceive prey are as varied and wild as the human imagination.

In some cultures, hunters will dress up as the animals, either as a form of camouflage or to pique the animal’s curiosity. One example from the ethnographic record among the eastern Siberian Chukchi notes that hunters in winter used camouflage in the form of a sealskin hat shaped like a seal’s head. ‘He crawled slowly, imitating the movements of the seal and from time to time scratching the ice with a special scraper to which seal’s claws were fastened.’ Another example, recorded among the San peoples of Southern Africa, highlights how, stalking a herd of zebras, two hunters would dress in the uniform of an ostrich – one man as the body of the ostrich itself and another hidden in feathers carrying a bow and arrows.

Even more salient in the record are acoustic lures of all types. In Melanesia, rattles made of coconuts, shells, and other loud objects are strung together and shaken on the top of water in the ocean to attract predatory sharks that believe the noises represent an animal in distress. Among virtually all groups of hunters worldwide, verbal mimicry of one’s prey is noted as being fundamental for attracting it. And while many calls are made the same way one talks or one sings, one acoustic phenomenon absent from most extant human languages is present across the globe in hunting: whistling. Around the world, hunters use high-pitched whistles, either with their mouths or with reeded instruments, to deceive birds and primates by mimicking their calls.

Beyond these visual and acoustic forms of deception, the ways humans deceive their prey take on a number of other forms.

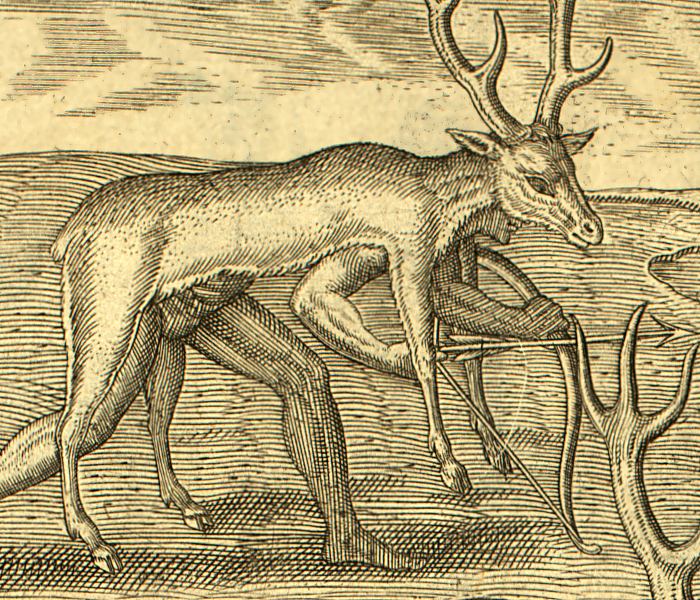

Among reindeer herders and in the Amazon, humans will capture female reindeer or male rivals of a mating species and use these potential ‘mates’ or ‘rivals’ to lure in unsuspecting lone males. Among the Kimam peoples of Papua New Guinea, hunters ‘take advantage of the natural curiosity of kangaroos by stamping on the ground from time to time while approaching their game, in imitation of a jumping kangaroo’. The Yupik people of St. Lawrence similarly tell stories about the carvings on the bottom of their whale-hunting boats – entranced by the carvings, whales would, seemingly voluntarily, position themselves to be harpooned by the hunters.

This is just a small set of the range of examples of these forms of deception across the ethnographic record. In our research using the Human Relations Area Files (HRAF), a massive standardized database of ethnographies used by anthropologists to make cross-cultural comparisons, my colleagues and I cataloged hundreds of examples from 147 cultures across the ethnographic record and across 7 continent groups (including Oceania), including ones representing most of HRAF’s hunter-gatherer groups.

While the existence of mimicry and deception in hunting may be intuitive, their pervasiveness across the globe suggests that they’ve likely had some importance in our evolutionary history. Although the fields of evolutionary psychology and cultural evolution have said a great deal about the cognitive mechanisms that are evolved, built up, and ultimately present in the human mind to interact with other agents, they have seriously overlooked another component: that other humans are not the only agents we have had to deal with. The interactions of minds in the landscape of our evolutionary history have included the minds of other animals, from birds to deer to fish to whales.

What can our interactions with other animals tell us about our own evolutionary history?

In their paper ‘Wild Voices’, anthropologists Chris Knight and Jerome Lewis present the hypothesis that the origins of human language may lie within our ability to mimic our prey. From an early age humans are adept at copying sounds, and it is our vocal plasticity – that is, our ability to make a wide range of precise and varied sounds – rather than lexical ability – our ability to understand many different concepts – that seems to separate us from most of our relatives.

As noted by the primatologists who studied the origins of language and human cognition, ‘while the number of distinct calls that animals produce is highly constrained, the number of signs that a parrot, dolphin, sea lion, or chimpanzee can learn to associate with a given stimulus or outcome is, if not limitless, certainly in the tens to hundreds’. The central question for them then is, ‘Why should an individual who can deduce an almost limitless number of meanings from the calls of others be able to produce only a limited number of calls of his or her own?’

In other words, why, among the mammals, do we exhibit such a degree of control over our faces and mouths and the ability to make what seems to be an exhaustless number of phonemes with an infinite number of combinations between them? The core question for language evolution may not be what its adaptive function is, or what we needed it for, but, more proximately, how it evolved.

One option is that our ability to make sounds coevolved with a protolanguage – humans steadily got better at making sounds in order to expand their vocabulary and the depth of the language. Individuals with better ability to use the protolanguage had more offspring, either due to the ability the language gave them to deal with the world, or social prestige conferred by mastering it.

But there are problems with this theory. First, language seems almost the paradigmatic network good: How could the community bestow prestige on users of a language they couldn’t understand – and who would they use it with? For this account to work, it would be easier for language to evolve among a group already possessing the basic physical abilities necessary to use it. Second, a story of where the initial stepping stones of vocal plasticity developed is missing in explanations of language that have focused on adaptation. In the words of Bjorn Lindbolm, one of the major challenges of our theories of phonetics is how we build ones that can ‘derive language from non-language’.

If protolanguage didn’t lead to vocal plasticity, one stepping stone may have been in the ability to mimic other sounds. In human language, the presence of warblish – the use of onomatopoeia for the imitation of animal calls – highlights how language and mimicry are intertwined.

Even within the trajectory of human development, the importance of animal sounds and calls in learning language is noteworthy. Native English-speaking readers may be familiar with Fisher-Price’s Farmer Says wheel, a classic toy that selects an animal at random, tells the child the animal’s name, then lets the child know what sound it makes. This pattern has been witnessed elsewhere around the world, including by Leonhard Schultze working among the Khoisan in the first decade of the twentieth century: ‘It is no hypothesis but an ascertainment of the actual state of affairs that, in the Nama language, the childish joy in imitating certain animal voices with words represents one way to rhythmical development.’

Not only would such an evolutionary story highlight the importance of the sort of vocal plasticity we find in language, but also the presence of whistling as an acoustic feature shared by humans around the world. As noted by the philosopher-poet Lucretius in his first-century BC work De Rerum Natura, ‘Men learn to mimic with their mouths the trilling notes of birds long before they were able to enchant the ear by joining together in tuneful song’. And the repetitive appearance of reeded implements like whistles used for mimicking birds and hooved animals may have further scaffolded the use of these tools in musical contexts.

This relationship between animal mimicry and the development of human cognition likely extends beyond language.

In his book Soul Hunters, ethnographer Rane Willerslev examines the relationship between Yukaghir nomadic hunters and their prey. He argues that the most common and ancient of the world’s religions, animism, has its origins in imitation. As defined by early anthropologist EB Tylor in the nineteenth century, animism at its core reflects the ‘idea of pervading life and will in nature’ – the idea that non-humans have a life force like humans. For Willerslev, the dances, songs, shamanistic transformations, and mimetic copying of prey may highlight the role that other animals had in the origins of human perspectivism, or our ability to take on the point of view of others.

Among the Mbuti foragers of West Africa, ethnographer Colin Turnbull noted that many magical rituals invoking animal spirits ‘convey to the hunter the senses of the animal so that he will be able to deceive the animal as well as foresee his movements’ (emphasis mine). Such an ability to take on the thoughts of others may have similarly scaffolded an understanding of one’s self (what phenomenological philosophers beginning with Martin Heidegger might refer to as the boundary of opposition).

In many of these cases of deception and mimicry, we can find explicit references to having to think like an animal thinks, act like an animal acts, and pretend to be an animal. These forms of mimicry include not only mimicking the behavior of prey animals, but also mimicking the behavior of their predators in order to become better hunters.

Among the Pawnee Indians of North America, ‘the chief scout crawled up cautiously on his belly, imitating the motions of a wolf so that he would not be detected by the herd. After the head scout had surveyed the situation to his satisfaction, he invited his fellow scouts to come up, each in turn crawling up like a wolf and taking a look around.’ Among the reindeer herders of North Asia, such imitation was widespread, leading one nineteenth-century ethnographer to remark: ‘to a certain degree also the imitation of the whole animal may occur among many primitive peoples. I cannot refrain from pointing out a few instances of this kind among other Paleo-Asiatic peoples . . . The nomadic Koryak, for instance, for whom the wolf is the most dangerous enemy of their reindeer herds, in winter wear caps of wolf fur.’

As in the case of language, the extensive use of taking on perspectives in order to deceive animals may have played a role in the evolution of our ability to do the same with other humans.

The ability for us to ‘get in the heads’ of other people or to develop theories of the knowledge they hold about things is known as theory of mind.

While many primates possess some level of theory of mind, none possess it on the level of our species, Homo sapiens, where it plays a central role as an advanced cognitive feature that sets us apart from other animals.

Such ideas feature prominently in theories of cognitive evolution, such as Robin Dunbar’s social brain hypothesis, which says humans evolved large brains to navigate their large social groups, and the related Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis, which says they evolved large brains to compete within these groups. Central to these social theories is the idea that human intelligence arose in order for us to deceive, outsmart, and manipulate others.

Our use of mimicry and ability to take on the perspectives of other animals presents us with a very straightforward interpretation of the Meat Paradox. By allowing the thoughts of other organisms into our minds, we built a pathway to developing empathy with our prey. Like the rest of the world’s predators, humans have to kill their prey to eat it. Unlike the rest of the world’s predators, we have the capacity to empathize with our prey.

Outside of a Western context, the ethnographic record is rife with explicit examples of hunter’s guilt, or the pain felt from taking an animal’s life. I opened this piece with one example of a trapper’s guilt from Willerslev’s book Soul Hunters, but numerous examples from his ethnographic experience are recorded, such as in an interview with one young hunter who stated, ‘When killing an elk or a bear, I sometimes feel I’ve killed someone human. But one must banish such thoughts or one would go mad from shame.’

Examples like these are abundant. Consider this excerpt from Robert Knox Dentan’s book on the Semai of Malaysia, where one hunter discusses the guilt felt after his hunts: ‘You have to deceive and trap your food, but you know that it is a bad thing to do, and you don’t want to do it.’ Dentan goes on to state, ‘trappers should take ritual precautions like those associated with the srngloo’ (hunter’s violence) . . . Animals, remember, are people “in their own dimension,” so that the trapping he is engaged in is profoundly antisocial, both violent and duplicitous.’

Moreover, many Southeast Asian and Oceanic cultures have been noted for their use of a live decoy pigeon tied to a cord or long pole to lure other pigeons – yet in several of these cases, ethnographers also note that there are cultural norms against killing one’s lure pigeon, which is afforded respect for the task it has done.

So is it the case then that our aversion to eating meat or, rather, our recognition of the pain caused by the process of eating meat, is a perversion of the modern environment?

The fact that hunters around the world at times experience something akin to a hunter’s guilt reads to me that these strange, contradictory feelings are, cognitively speaking, rather old.

The earliest paleoanthropological evidence for human hunting, at hominin kill sites, indicates that our earliest ancestors were ambush predators. The distribution of hominin kill sites across Africa tells us that our ancestors tended to kill their prey around natural landscape features that provided visual cover.

Despite not having the typical means afforded to predators, such as speed, claws, teeth, or poison, humans have nevertheless reigned as the single most effective predator on the planet – something we’ve done simply with our brains.

The idea that these cognitive features may have come from animals is provocative, but when applied to human contexts they are noncontroversial. Narratives abound on the roles that vocal plasticity plays for language, that imitative learning plays for cultural learning, and that empathy plays for emotional regulation. But while a great deal of attention has been paid to the fact that the human mind is shaped by the interaction of humans with other agents, little has been paid to the fact that nonhuman animals are agents too.

As noted by the late-twentieth-century naturalist Paul Shepard, ‘Animals embody every quality found in the human personality. In the whole range of human temperament and character there is nothing unique, nothing not found as some aspect of another species. It is the only other place they are found.’