Society has free-ridden on women for millennia, benefiting from the children they’ve had while bearing few of the costs. But as women have gained other options, birth rates have fallen.

How many children should we be having? It’s a question that’s had slightly more airtime in recent months than usual. The UK charity Population Matters demonstrated outside COP26 in November with a giant inflatable “big baby” to draw attention to the environmental impact of children as a reason to have fewer of them. At the same time, the latest data say that 2020 has seen birth rates in Britain fall to unprecedented lows, which has prompted concerns that low fertility “will damage our society” and “spell economic stagnation”.

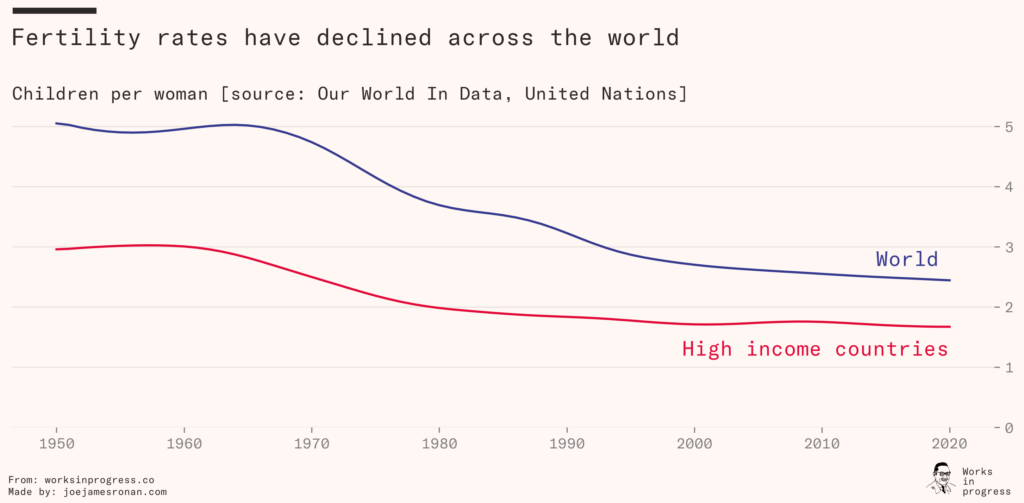

These numbers suggest that the pandemic has accelerated one of the most remarkable yet under-reported trends of the last fifty years: the great baby bust. In almost all the world’s developed nations, fertility dropped below replacement rate in the latter half of the twentieth century, and shows no sign of resurfacing.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

The resulting population crash, with ever smaller numbers of working-age adults to support the elderly, is predicted to seriously threaten the long-term political future of these countries. In the UK, immigration of young adults from elsewhere has provided a buffer, but has also contributed to shrinking and ageing populations in migrants’ home countries, and as more and more countries enter population decline, immigration may become less viable as a solution.

Contrary to the view of Population Matters, this may be bad rather than good news for our ability to deal with climate change. Smaller populations are linked to slower technological development, and ageing populations seem to distort countries’ balance of political power and turn priorities away from the ambitious investments in infrastructure and innovation that we will need to face the challenges of the twenty-first century.

Despite significant public interest in how many children are born, children are typically seen as a private good. It is assumed that when individuals decide to reproduce, they are the ones who benefit, and they are the ones responsible for the costs. But this way of looking at things neglects that the private decision to have a child has an important positive externality – it benefits us all for there to be enough new people in each generation to sustain our way of life.

So what is the cost of having a child? One analysis suggests that supporting a child from birth until the age of twenty-one costs almost a quarter of a million pounds in modern Britain, with most of this going into childcare and education, followed by food, holidays, and clothing. Having children is the most expensive decision many of us make in our lifetimes.

But the cost of having children is not just measured in money spent. As any parent will tell you, children eat up an enormous amount of time and energy, both mental and physical. Raising a child is work, in the sense that it requires resources that can’t then be used elsewhere. I don’t mean by this that having children is not rewarding or worthwhile. Running a marathon is also work in the same sense, and yet it’s something many people choose to do because they derive great satisfaction from it. It is not, however, something you can do “for free” – that is, without some cost in time, energy, and money, which may mean other activities have to be set aside.

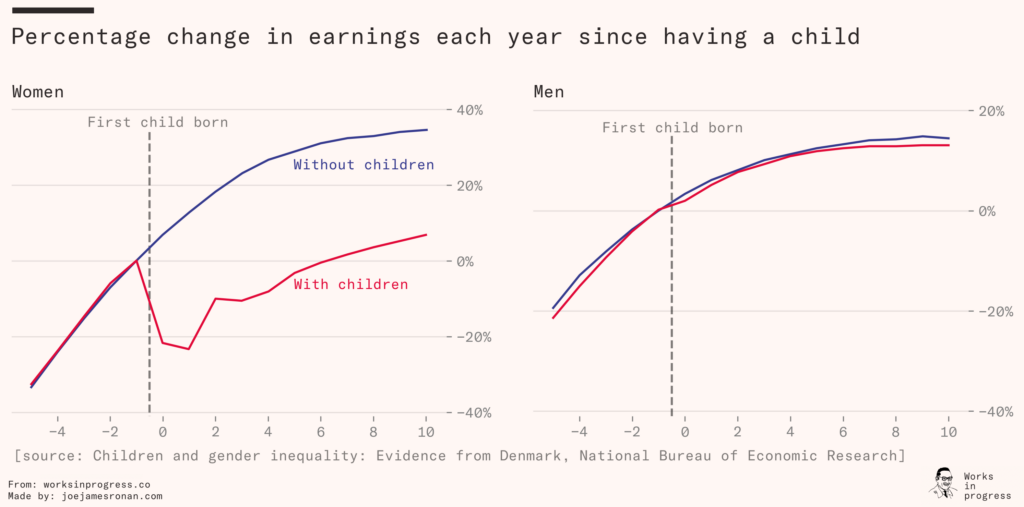

Children are almost always costly for both parents. A disproportionate cost, however, is paid by mothers. Evidence suggests that the “gender pay gap” is actually a motherhood pay gap: women’s earnings are on par with their male colleagues until they have children, at which point they drop behind and never catch up. One study in Denmark compared the earnings of women who were successful in their first IVF treatment with women who were unsuccessful (but may have had children subsequently), highlighting the enormous direct cost to women’s earnings from becoming mothers.

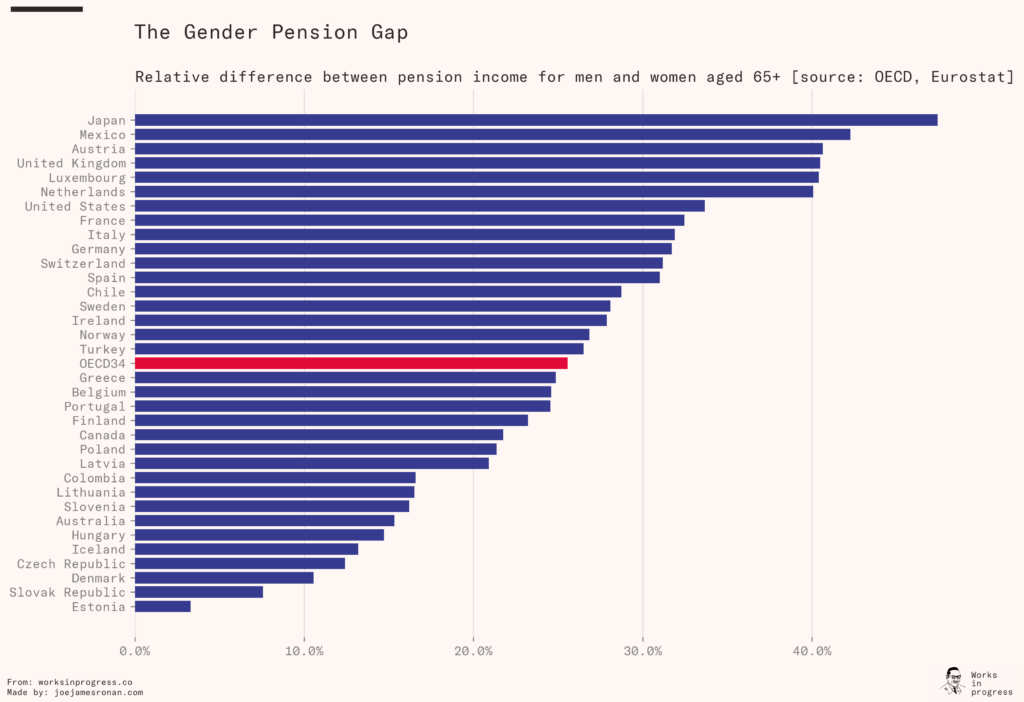

This wage gap accumulates over a lifetime and results in a “pension gap”, where women retire with substantially smaller pensions than men across the world.

Even if both parents earn a full-time salary, in most heterosexual couples there is an expectation that the woman is responsible for household management, meaning mothers tend to carry a mental load that fathers don’t, as well as doing the lion’s share of housework generated by children.

There’s another cost of children, one which can only be borne by women: physically producing them. In the UK, until midway through the twentieth century, giving birth meant roughly a one in two hundred chance of death. Although today’s mortality rate is – miraculously! – nearly a hundred times lower, giving birth in a developed country still carries more risk to life than many extreme sports, and globally remains one of the leading killers of reproductive-aged women.

And there’s not just death to worry about. Even with good medical care, serious and lasting health consequences from pregnancy are shockingly common. Nine in ten women who deliver a baby vaginally will suffer genital injuries, and at least six percent sustain damage that requires surgical reconstruction and can carry life-changing consequences. A third experience incontinence. One in ten women have some degree of organ prolapse after the age of fifty , for which previous pregnancies are an exacerbating factor. Diabetes is a relatively common pregnancy complication, and in a small proportion of cases it persists longer term. Other common changes to the body are more benign but no less permanent, from weight gain to varicose veins and even increased shoe size. Having children is not free: it is something women physically pay for.

At a fundamental level, building a new person from scratch requires a massive decrease in entropy, so by definition requires work to be done by the mother’s body, which means more calories have to be taken in. Specific nutrients and minerals are also needed as raw materials. These must be either supplied by the mother’s diet – which explains pregnancy cravings for oddly specific foods, or non-food substances like soap or clay – or requisitioned from her own body. During pregnancy, a woman’s bone density drops by up to ten percent, as her calcium reserves are depleted by the demands of a growing foetus and subsequent breastfeeding.

For most of history, women had essentially no choice but to carry out this work under whatever gruelling or exploitative terms were offered. In her autobiography, Margaret Sanger writes about a young woman living in a cramped tenement in 1912, already a mother to three children, who feared that “another baby will finish me”, and was later proved correct, dying after having been given no advice except to tell her husband to “sleep on the roof”.

Until the late nineteenth century, marriage – the only realistic way for many women to support themselves – meant becoming a legal subsidiary of your husband, rather than a person in your own right, with no right to the clothes on your back or to your own children. There was no right to refuse sex within marriage – in the UK, this remained the case until disturbingly recently, in 1991. Without effective contraception and limited ability to abstain from sex, pregnancy and childbirth were effectively compulsory.

Thanks to feminism and advances in contraceptive technology, having children is no longer simply a woman’s lot in life whether she likes it or not. Contraception available today is effective, openly discussed, and doesn’t necessarily require the cooperation or knowledge of male partners. In many countries, women can safely and legally end pregnancies via abortion, rather than having to risk their lives to do so, as was the norm in the UK half a century ago.

Beyond this, the world has changed from one in which women sign over lifetime sexual access in exchange for bed and board to one in which women interact with society as persons in their own right, and can expect to make a living by themselves. Women’s legal rights in the UK to inherit and own property, divorce, make contracts in their own name, and hold copyright over their own work have all been won in the last century and a half.

The result of these developments is that, for women in many parts of the world, having children is now optional – a major upheaval to the social order whose full significance will take some time to be felt. One general consequence is that rates of childbearing can now respond rationally to incentives to a historically unprecedented extent, especially the incentives specific to mothers. If large costs are imposed on women for having children, we can expect fewer to do so.

One major cost of having a child – risk of death – has decreased by orders of magnitude within the last century. At the same time, however, several important incentives for individuals to reproduce have evaporated. Children today don’t contribute economically to the household, helping on the family farm or going out to earn a wage. Instead, parents invest considerable time and resources into supporting their children’s education, which often now extends into their twenties. Since the basic needs of the elderly are nominally met by the state, people have less reason to have their own children as insurance for old age.

Above this, now that education and paid work are the norm for women, there is an opportunity cost from taking time out of the workforce to raise children, which didn’t exist a century ago. Time spent on unsalaried work at home is time that could be spent advancing a career and adding income to your household, rather than simply what you’d expect to be doing anyway.

Add to all this the difficulty young people face in finding stable housing and employment in time to have children, and plummeting birth rates should come as no surprise.

To conservatives, falling birth rates are a regrettable downside of women’s empowerment. But they are also the result of fairness, ending an open season of free-riding. Historically, society has enjoyed the positive externalities of high fertility rates without bearing many of the costs. Because women had little control over their own fertility, it was impossible for them to negotiate terms, meaning exploitation was all but inevitable. Now women are in a stronger bargaining position with their fertility than at any other point in history. But the private incentives to have children are dropping. If we want fertility to stay high, we will have to offer better incentives than we currently do.

This could mean reversing cuts to child benefits and government-sponsored childcare. France, which has the highest birth rate in the EU – with 1.86 children per woman in 2019 compared to an average of 1.53 – is also among the highest spenders on childcare and early education of all OECD countries. Sweden and Iceland, two of the other top spenders, are also doing well on fertility relative to the European average, with 1.71 and 1.74 children respectively per woman.

The French system for child benefits explicitly encourages larger families. By contrast, in the UK, payments have been limited to a family’s first two children since 2017, with a controversial “rape clause” that grudgingly allows for an additonal child if it was not conceived through consensual sex. This approach treats children as a luxury to be rationed, and perversely implies that if you fall pregnant with a third child while in financial hardship, the government would rather you had an abortion than provide state help.

Being friendlier to mothers could also mean restructuring working culture so it is more family-oriented. Compare Sweden and Iceland, which have some of the world’s most generous and flexible protections for working parents, to countries like Japan, Singapore, and South Korea, which are notorious for having punishingly long working hours and fertility rates barely above one child per woman. Long and inflexible hours, modelled on male employees whose wives take care of everything at home, are virtually impossible to manage if you have primary responsibility for a child – and a culture that expects postpartum women to leave their newborns and go back to full-time work is not humane. Why would women want to have babies if they wouldn’t even be able to spend time with them?

Every country in the world could improve the standard of maternity care provided by the state. In the United States, new mothers are routinely hit with hospital bills of tens of thousands of dollars, driving some to bankruptcy. As well as being a moral travesty, for a country that has had five decades of below-replacement fertility, this is a bizarre form of self-sabotage.

The good news is that women’s ideal number of children, according to survey results across OECD countries, is slightly above two. In other words: women are happy to have more children – we just need to meet them halfway.

We can draw an analogy between fertility and other public goods, such as scientific research. Like having children, scientific research is conducted by private actors – in this case universities and pharmaceutical companies, rather than individual women and couples. The pandemic has shown that we all have an interest in this research taking place – to develop and test vaccines, for instance. But the rewards available on the free market (patents and perhaps prestige) are nowhere near enough to incentivise the massively expensive enterprise of vaccine development, with huge up-front costs and no guarantee of success. Similarly, the incentive structure as it currently stands is insufficient for people to have the number of children they want.

If it was left to the market alone, much of the scientific research we rely on simply would not happen – even though researchers want to do the work, and we all benefit from it being done. To get around this, our government spends over £10 billion a year subsidising scientific research: increasing the incentives available so that private actors continue to produce this public good.

Since it looks as though babies will be at a premium in the twenty-first century, perhaps we should similarly think of optimal population fertility as something worth paying for from the public purse. We aren’t accustomed to thinking about fertility as a public good in this way, because it has always been one that women have had to provide for free. The current approach seems to be stuck in the same mindset: though we fret about crashing birth rates, we continue to act as though having children is a personal luxury, offering only crumbs of support. But producing children and raising them has always been work. It’s time that work is given the recognition it’s due.