Every hundred South Koreans today will have only six great-grandchildren between them. The rest of the world can learn from Korea’s catastrophe to avoid the same fate.

South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world. Its population is (optimistically) projected to shrink by over two thirds over the next 100 years. If current fertility rates persist, every hundred South Koreans today will have only six great-grandchildren between them.

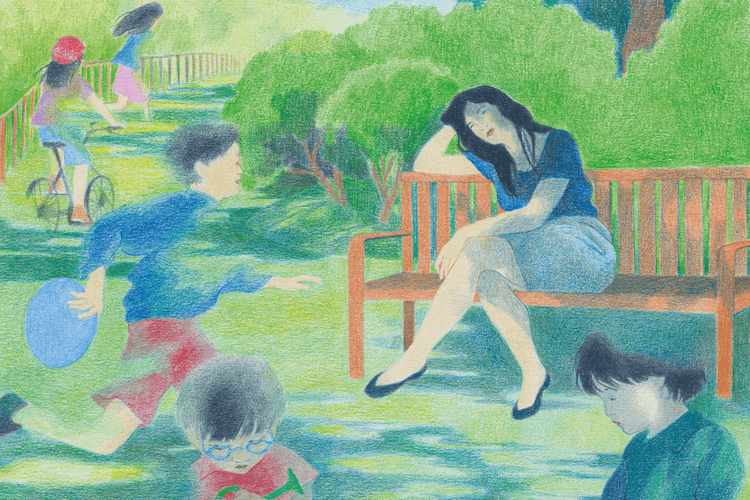

This disaster has sources that will sound eerily familiar to Western readers, including harsh tradeoffs between careers and motherhood, an arms race of intensive parenting, a breakdown in the relations between men and women, and falling marriage rates. In all these cases, what distinguishes South Korea is that these factors occur in a particularly extreme form. The only factor that has little parallel in Western societies is the legacy of highly successful antinatalist campaigns by the South Korean government in previous decades.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

South Korea is often held up as an example of the failure of public policy to reverse low fertility rates. This is seriously misleading. Contrary to popular myth, South Korean pro-parent subsidies have not been very large, and relative to their modest size, they have been fairly successful.

The story of South Korean fertility rates is thus doubly significant. On the one hand, it illustrates just how potent anti-parenting factors can become, creating a profoundly hostile environment in which to raise children and discouraging a whole society from doing so. On the other, it may offer a scintilla of hope that focused and generous policy can address these problems, shaping a way back from the brink of catastrophe.

Career-motherhood conflict

In every developed country, women struggle to reconcile their careers with a satisfying family life and their preferred number of children. This tradeoff is exceptionally severe in South Korea.

Despite its very high level of female education, South Korea has the largest gender employment gap in the OECD. There is almost no employment gap between men (73.3 percent) and unmarried women without children (72.8 percent). The gap is driven by the fact that large numbers of women stop working when they have kids: only 56.2 percent of mothers work, the fourth lowest in the OECD.

In South Korea, mothers’ employment falls by 49 percent relative to fathers, over ten years – 62 percent initially, then rising as their child ages. In the US it falls by a quarter and in Sweden by only 9 percent.

South Koreans work more hours – 1,865 hours a year – in comparison with 1,736 hours in the US and 1,431 in Sweden. This makes it hard to balance work and motherhood, or work and anything else.

There is intense pressure from employers for women not to have children: in surveys, 27 percent of female office workers report being coerced into signing illegal contracts promising to resign if they fall pregnant or marry.

South Korean work culture is notoriously sexist. After their long work days, colleagues are expected to go out drinking together. Alice Evans, a social scientist, spoke to a young South Korean woman who went to a karaoke bar with her colleagues and found they hired a sexy woman to serve them drinks. Her boss, noting her discomfort, chided her: ‘You shouldn’t be surprised by this, at your age.’

In response to these taxing hours, and with bosses unwilling to make accommodations to mothers, over 62 percent of women quit their jobs around the birth of their first child. (Some go back soon afterwards, which is why the total fall in employment is slightly less than this, at 49 percent.)

By the time a child turns ten, their mother will have seen her earnings fall by an average of 66 percent, considerably higher than the earnings penalty in countries including the US (31 percent), UK (44 percent), and Sweden (32 percent).

Put together, all this means that having children is extremely expensive for South Korean women in terms of their careers and earnings.

Resource-intensive parenting

Perhaps due to high infant mortality rates in the past, Koreans treat a child’s first birthday as a very significant milestone. A Doljanchi is a party and ceremony when the child is dressed in an ornate traditional outfit and presented with a series of objects – a pen, a thread, money, a sword – and what they choose is meant to show what the future has in store for them: academic success, longevity, wealth, or martial prowess respectively. Parents will often try to coax their child to choose something specific but, being only one, the child is usually uncooperative.

Traditionally, this party would have been done at home. Now, they have become more lavish. They are typically hosted like weddings: in hotel ballrooms with long guest lists, party favors, and multicourse meals.

As with weddings, the costs of the ceremony vary from family to family. But a typical Korean family can expect to spend a month’s wages on the Doljanchi.

Today, South Korea is the world’s most expensive place to raise a child, costing an average of $275,000 from birth to age 18, which is 7.8 times the country’s GDP per capita compared to the US’s 4.1. And that is without accounting for the mother’s forgone income.

Fueled by intense competition for university places, cram schools and private tuition are popular in many low-fertility East Asian countries. Uptake is also high in Taiwan and Singapore, and 38 percent of Chinese children used the country’s shadow education system before the government clamped down.

But South Korea is even worse. Almost 80 percent of children attend a hagwon, a type of private cram school operating in the evenings and on weekends. In 2023, South Koreans poured a total of $19 billion into the shadow education system. Families with teenagers in the top fifth of the income distribution spend 18 percent ($869) of their monthly income on tutoring. Families in the bottom fifth of earners spend an average of $350 a month on tutoring, as much as they spend on food.

On top of the expense, these are grueling for the children themselves, and they start very young. Nearly half of children under six receive some form of private tuition. As a Korean TikToker explains, even if you have the money, you can’t necessarily get your teenager into the most elite hagwons. They have to have attended the right hagwons when they were younger to have a shot at getting in later.

These high school hagwons have grueling schedules. During term time, students typically have days that run from 7am to 2am, starting with morning study sessions before school and finishing with homework in the library. During school holidays, lots of students go to boarding hagwons where the days are tightly scheduled from 6am to midnight and include tests late in the evening.

Parents don’t feel like they can just leave their children to fend for themselves in the public education system. Because most students, upon starting high school, have already learned the entire mathematics curriculum, teachers expect students to be able to keep up with a rapid pace. There’s even pejorative slang for the kids who are left behind– supoja – meaning someone who has given up on mathematics.

The intense schedule and the lack of sleep is why places like Daechi, a neighborhood renowned for its hagwons, have screaming pods for frustrated teenagers to let off some steam.

Since the 1980s, the South Korean government has regarded shadow education as a ‘social evil’ that widens inequality. The government even temporarily banned private tuition, but tutors simply went underground and charged high ‘risk premiums’. The ban was removed in 2000, but the government is still trying to reduce demand by curfewing operating hours, providing after-school teaching of its own, and regulating the shadow education industry. In Seoul today, all hagwons must close by 10pm. But some operators have responded by simply switching off the lights and continuing with lessons in the dark, or by loading students onto a bus to carry on teaching on the road. It is hard to quash the system when demand is so strong.

South Korea already has the highest share of young tertiary graduates in the OECD, and its competitive job market means that degrees from the most prestigious universities are immensely valuable. The acceptance rate for the country’s top three universities, known as the SKY colleges, is just one percent.

Parents know that unless they are wealthy, having a second child will damage their ability to pay for the best education for their first. Korean parents with more children usually spend less per child on education and 27 percent of Korean parents, when polled, say they think the high education and childcare burden is the main reason for falling fertility.

High performance in the university entrance exam is an arms race: if everyone becomes better at the exam, nobody is better off. Yet parents are individually incentivized to force their children to take part, at great cost to their whole families.

The decline of marriage

Across the world, men and women are more and more divided. In the public sphere, this manifests as political polarization in which gender is becoming a salient political division, just like class and age. In the private sphere, we see that people are living alone and eschewing romantic love.

As with the other trends we have discussed, this is true everywhere, but in South Korea it is happening to an extreme degree. About 43 percent of South Korean women aged 15–49 are married, compared to 52 percent in the US.

A chasm between young South Korean men and women has been opening up for years. In 2018, the MeToo movement took off in the country. The inciting event was when prosecutor Seo Ji-hyun accused a Justice Ministry official of groping her at a funeral in 2010. Initially she just asked for an apology and was, instead, demoted. She uploaded evidence of this in 2018 with the MeToo hashtag and was interviewed on television.

Her story kicked off an investigation in the prosecutor’s office and a series of other women, in other sectors, were emboldened to come forward. At first, the MeToo movement found broad popularity among younger people: 77 percent of South Korean men under 30 said they supported it.

But Korean men turned on the movement and there were several suicides by men accused of wrongdoing. The Journalist Association of Korea says that the press, in general, was too sensationalist in its reporting and didn’t respect the rights and privacy of the people involved.

Because of decades of sex-selective abortion, young men in Korea outnumber young women. For today’s 30-year-old South Koreans, there are 115 men for every 100 women. This skewed sex ratio, combined with the fact such a large proportion of young Korean women are persistently single, means that men face a punishing dating market. Combined with a competitive labor market, in which men are competing for jobs against their better-educated female counterparts, and two years of male-only conscription, Korean men who are unlucky in love and employment may end up blaming women for their problems.

The resentment goes both ways. The now-defunct feminist troll site Megalia used a pinching hand as its logo to make fun of men for having small penises, supposedly mirroring the high standards of beauty that Korean women are held to by men. Even though the website shut down in 2017, the gesture is still associated with misandry.

The ‘finger pinching’ conspiracy started in May 2021, with an advert for a convenience store chain showing a hand pinching towards a small sausage. There was outcry and the company pulled the advert and apologized. The protestors said the gesture was a misandrist dog whistle and several other companies and women were attacked for supposedly using it to mock Korean men.

By this time, in 2021, only 29 percent of young men said they still supported MeToo. Now, majorities of young men view themselves as victims of female supremacy and of sex-based discrimination.

In 2022, Yoon Suk Yeol was elected President of South Korea on a tide of male support. Over half (59 percent) of male voters aged 18–29 voted for Yoon, in comparison with only 34 percent of women aged 18–29. Yoon embraced the gender war narrative, attributing South Korea’s ultra-low fertility to feminism and arguing that structural discrimination against women did not exist in South Korea. He also vetoed a law that was attempting to expand the definition of rape to include all nonconsensual sex, making it so that violence and intimidation were not necessary prerequisites.

In the June 2025 presidential election, the two conservative candidates together won the support of 74 percent of men in their twenties and 60 percent of men in their thirties. Meanwhile, only 36 percent of women in their twenties and 41 percent of women in their thirties voted for these candidates.

Conservative gender attitudes remain common across the country. Fifty-three percent of South Koreans still agree that ‘when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women’. A third of South Koreans say that a university education is more important for a boy than for a girl.

Other countries are seeing political polarization between the sexes. Across all ages, more men voted for Donald Trump in 2024 than women. Young Americans are also increasingly saying that shared political values are an important feature in a partner. In other places, including Germany, Poland, and the UK, younger men are moving right as younger women move left.

Yet South Korea’s polarization is particularly stark, because it has happened so quickly and because gender issues have become so central to the country’s politics.

This gap in values might be one reason that younger South Koreans are less likely to date and marry. It could also be a symptom of a culture in which men and women live bifurcated lives: they go to different schools, consume different media and news, and socialize in unmixed groups. Less than half of Korean women in their childbearing years are married.

But marriage rates have fallen so fast that this number doesn’t give us a full picture. In many countries, the age at which women are getting married for the first time is increasing and the number of women who will ever get married is decreasing. It is difficult to fully separate these trends: how can we know if the decrease in the number of 30-year-olds marrying is going to show up as an increase in the number of 35-year-olds marrying until it has happened? But other statistics imply that most of these women aren’t ever going to marry.

In Korea the average age at which women have their first marriage, if they marry at all, is 31. This is within the standard range for a rich country: in the US it is 29, in the UK 31, in Japan 29 and in Sweden it’s 35. But while about half of American women are married by their early thirties, a staggering 77 percent of Korean women aged 30–34 are unmarried.

South Koreans in their twenties have been less and less likely to be dating over the decades (from 40 percent without a partner in 1991 to 65 percent in 2018) and singleness is rising in all age cohorts.

The decline in marriage is particularly significant in Korea – like most East Asian countries, childbirth out of marriage is much rarer than in other developed countries. Today, only 3 percent of babies in South Korea are born to unmarried parents, compared to 40 percent in the US and 55 percent in Sweden. The collapse of marriage in Korea, therefore, means an even greater collapse of birth rates than it would elsewhere.

Where South Korea is unique: antinatalist campaigns and negative population momentum

So far, South Korea’s fertility crisis sounds similar to that in the rest of the world – just a much more extreme version. But one cause of its low fertility rate is unusual, especially compared to the Western world. This is the legacy of decades of sustained government action to reduce fertility.

In 1961, a military junta led by General Park Chung-Hee seized power. At the time, the average South Korean woman had six children. Park believed that shrinking family sizes would fuel economic development by freeing up more women to work and decreasing the number of dependents per worker.

Park’s government started by giving every hospital a family planning unit and promoting contraceptive measures, particularly vasectomies and IUDs. In 1963, every government department was ordered to participate in the national effort: the Defence Ministry offered soldiers vasectomies and the Education Ministry incorporated the supposed dangers of overpopulation into the school curriculum.

In the 1970s, the government introduced tax breaks for families with no more than two children. Parents with less than three children who underwent sterilization received priority access to public housing. There were extra social security payments for parents of small families who opted for sterilization.

Official messaging also promoted smaller families. The government’s first antinatalist slogan was ‘Have few children and bring them up well.’ Later posters encouraged parents to prioritize ‘quality over quantity’, with mottos such as ‘Let’s have two children and raise them well’, or the frantic ‘Two children is already too many!’

Family planning propaganda also attempted to address South Korea’s cultural preference for male over female children, which meant that couples who had only daughters were motivated to continue having children in pursuit of a son. The sex preference was a strong one. In 1971, 50 percent of South Korean women who were asked what a woman should do if she could not give birth to a boy said that the woman should let her husband try for a son with a different woman. Slogans introduced on this matter included “A well bred girl surpasses ten boys”.

In many ways, South Korea was simply doing what the world’s great philanthropists, policymakers, and politicians of that time wanted. Fears about a busy, hungry world went mainstream in the sixties. The Kennedy administration publicly argued that population control was a legitimate policy focus. In 1967, President Lyndon B Johnson asked Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ‘to join a truly worldwide effort to bring population and food production back into balance’. Henry Kissinger was worried that ‘excessive population growth’ would hold back economic development and social progress and would undermine US interests by creating political tensions that could lead to instability. The president of the World Bank, Robert McNamara, made family planning a priority for the Bank, giving direct financing for contraception in 1970 and tying population targets to aid. John D Rockefeller III, who founded the Population Council, went on to chair Nixon’s population commission. He spent Rockefeller Foundation money on research and education about contraception.

By 1976, Korea’s family planning policy, centering on the promotion and distribution of contraceptives, is estimated to have averted between 1.8 million and 2.1 million births. And it did so remarkably cost-effectively, at a cost of just $103 per prevented birth in today’s money. Between 1960 and 1978, South Korea’s total fertility rate fell from six children per woman to three. Comparable drops took 96 years in the UK and 82 in the US.

These antinatalist policies survived the end of Park’s dictatorship in 1979. The fertility rate continued to plummet, falling below replacement rate (2.1 children per woman) in 1984. In 1989 the government stopped giving out free contraceptives and relaxed the sterilization drive. By 1990, South Korea was experiencing the consequences of these policies: the average age of the country was now rising, its working age population was clearly destined to fall, and the country now had an imbalanced sex ratio caused by sex-selective abortions. In 1994, the government officially abandoned its population suppression targets. It would begin its explicitly pro-natalist policies only 11 years later.

Once the number of people at or below reproductive age has shrunk below a certain level, averting population decline becomes extremely difficult. Even if the remaining young people rapidly increase their fertility, there are not enough of them to avert decline from attrition in larger, older groups. And a culture dominated by older and childless people becomes less child friendly. Schools and parks close down and institutions are shaped to cater for the majority. Korea is known for its ‘no children’ policies in many cafes and restaurants.

Between 1990 and 2023, the number of South Korean children declined by 50 percent, while the number of over-65s increased by 340 percent. For South Korea to just maintain its current old-age dependency ratio – 3.9 working adults for every person over 65 – in 30 years’ time, its fertility rate would have to skyrocket to over 10 babies per woman. If it were to fall only as low as Japan’s dependency ratio, the lowest in the OECD – 2 working adults for every person over 65 – it would still have to increase its birth rate to 4.2 babies per woman. This requires extreme behavioral change in a narrowing group of people.

While the number of South Korean children has halved since 1990, the US has seen its number increase by 11 percent, the UK 9 percent, and Sweden 19 percent. While these countries all have large cohorts of older people who will be difficult to replace as they die, the number of young people has not fallen to South Korean levels, both because of South Korea’s extra-low fertility rate and low levels of immigration. Foreign nationals represent only 5.1 percent of its population. In contrast, with so many more young people, the mountain that the Americans, Brits, and Swedes must climb to stabilize populations is far less steep than that faced by South Korea’s leaders.

Childbearing decisions are memetically influenced. They are shaped by the decisions peers make and the examples they see around them in everyday life. Thirty years of antinatalism have left their mark on South Korean attitudes. By normalizing small family sizes and childlessness, the government ushered in a self-perpetuating culture of lowered fertility. Only 28 percent of unmarried South Koreans aged 19–49 now say they want children, while 51 percent of childless Americans aged 18–34 say they want children.

South Korea’s recent pro-child policies have still probably helped

Since 2022, in an explicit effort to raise fertility rates, the South Korean government has given couples a grant of $1,500 upon the birth of a first child. As of 2023, this is followed by $528 a month until a child is one, $264 until a child is two and then $150 a month until elementary school starts. Every South Korean baby is now accompanied by some $22,000 in government support through different programs over the first few years of their lives. But they will cost their parents an average of roughly $15,000 every year for eighteen years, and these policies do not come close to addressing the child penalty for South Korean mothers.

While the government’s attempts to revive fertility might appear unsuccessful, the situation would likely be worse without them. New evidence, which analyzes the variation in the generosity of South Korean baby bonuses across districts and time, suggests that more generous cash transfers are causing more babies to be born.

For each ten percent increase in the bonus, fertility rates have risen by 0.58 percent, 0.34 percent, and 0.36 percent for first, second, and third births respectively. The effect appears to be the result of a real increase in births, rather than a shift in the timing of births. For example, where a district increased the generosity of a bonus for second births, more second children were born, but births of first and third children did not change. This suggests that the decline would have been faster and harder in the absence of pro-child policies. These gains, while real, just aren’t enough to counteract decades of antinatalist policy, the world’s toughest gender divide, the world’s biggest marriage penalty, and the world’s most intense schooling culture.

This aligns with global examples suggesting that child-friendly policies can raise fertility rates. For a century, France was Europe’s lowest-fertility nation. After launching an active pronatal campaign in the 1920s, France is now Europe’s highest-fertility country. The French sides of the Franco-Spanish border and the Italian-Franco border have higher fertility than the regions they border. The program includes family-friendly tax breaks, baby bonuses, and strong maternity employment protections. France has consistently sat about 0.3 children above the Western European average.

Similarly, South Tyrol in northeastern Italy has a fertility rate higher than any other Italian region, and it has actually increased since the 1990s. South Tyrol has a highly functional childcare system and gives parents a monthly €200 payment for each child under three.

There are other examples too. Nagi in rural Japan saw its fertility rate increase from 1.4 in 2005 to 2.7 today after giving parents cash, cheap childcare, housing subsidies, and free healthcare for children. Australia, Spain, Poland, the UK, and Russia all had more births after introducing different policies that gave families more money. Germany increased births among educated women by creating a generous earnings-dependent parental leave allowance.

It may be too late for South Korea. It is surrounded by real and potential enemies, including one which is committed to its destruction, and its army relies on a rapidly waning number of young conscripts. As its population gets older, more and more resources are going to be spent sustaining the elderly. This means less money for baby bonuses and more for nursing homes, as well as perpetually increasing taxes and hours. At some point, the few youngsters that are left may start to leave for less burdensome futures elsewhere, worsening the load on those that remain.

This is a future worth avoiding: the rest of the world would be much poorer without South Korea. South Korea is an extremely innovative nation. It files the most patents per capita in the world, filing 3,600 patents per million people, more than double the patents of Japan in second place and triple those of China in third.

South Korea has a genuinely unique culture. Isolated from the rest of the world, Korean culture has been able to grow and flourish on its own. For example, Koreanic languages (Korean and Jejuan, from the island of Jeju in South Korea) are considered to be an isolated family of their own, totally separate from other languages in East Asia. And its cultural exports, from K-pop and K-dramas to skin care and Korean barbecue are popular throughout the world.

Along with its technology and culture, Korea is also exporting a warning about what is to come for us all. Much of the world is getting older for the same reasons as South Korea. Families, especially mothers, are made poorer when they choose to have children. As the demands of educational institutions get more extreme, children are getting more expensive to raise. And while less extreme than in Seoul, men and women are drifting apart around the developed world.

South Korea is often seen as a testament to the futility of pro-child policies. This conclusion is the opposite of the truth. South Korea’s pro-child policies have not been that well-funded and may not have been perfectly targeted, but they have still been fairly effective. They just fall far short of what is necessary.