Quartz helped Japan’s watchmakers nearly drive Switzerland’s watch industry out of business. But the Swiss fought back.

It’s April 1984. Two men are sleeping in a car park in Basel. Each morning they wake, leave their borrowed Volkswagen Westfalia, and wash in the train station toilets. Then they go to their new stand at the Basel fair: the high point of the watch industry’s annual calendar. Their stand is arresting: every case is empty. With only two models to show, probably better not to show them at all. Instead, the pair focus on pitching the great and the good of the Swiss watch industry. If anyone asks them where they’re staying, they’ll say the Hilton.

The two men are Jacques Piguet, born into a family of watchmakers; and Jean-Claude Biver, a disgruntled ex-exec from Omega. The plan is to relaunch Blancpain, a brand they’d acquired in 1981 but had yet to bring back to life. The move is somewhat audacious: the Swiss watch industry is in a tailspin, disrupted by a new technology, the quartz wristwatch, that has left Switzerland’s traditional watchmakers obsolete.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Japanese factories are churning out watches that are faster, cheaper, and more precise than the Swiss mechanicals could ever hope to be. Over half of Switzerland’s watch companies collapse. Two thirds of its watchmaking jobs disappear. But Swiss watchmaking isn’t dead yet, and a handful of people are about to snatch it from obsolescence.

From the city to the mountains

The story of Swiss watchmaking began in Geneva in the 1540s. At the behest of John Calvin, the city imposed a ban on jewelry, the craft that had sustained Geneva’s artisans. The law, however, left one deliberate loophole: timepieces, those most practical and Protestant of devices, were still permitted to be worn. Denied their old market, the city’s artisans, joined by religious refugees from France and Italy, retooled and got to work.

At that point, despite Calvin’s strictures, watches remained more a curiosity than a necessity. When mathematician and astrologer Thomas Allen visited his friend, Sir John Scudamore, at the turn of the seventeenth century, and decided to bring his watch with him, a maid presumed its ticking to be the noise of the devil, and promptly threw it out of the window.

Time was measured in a mongrel fashion: references to ‘one o’clock’ in diaries sat comfortably alongside those to prime (first daylight prayer) and vespers (sunset prayer). Few people owned watches; most relied on public clocks and sundials, each town stubbornly keeping its own solar time. Precision in timing was reserved for only the most important moments, most obviously births and deaths. For everything else, a half day, or maybe a quarter day, if the subject were feeling adventurous, would suffice.

Time remained this way until the turn of the eighteenth century, with the needs of industrialization and navigation demanding a greater degree of precision. Aided by the 1656 invention of the pendulum clock by Dutch inventor Christiaan Huygens, clocks began to migrate from church towers to parlor walls: between 1740 and 1780, Bristol probate records list more clocks than mirrors. Clocks had become so commonplace that, at the very moment of Tristram Shandy’s conception, the deed stalls on his mother’s anxious reminder: ‘Pray, my dear, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?’

As watches became small and reliable enough to carry, producing them seeded thriving workshops in London, Paris, and Amsterdam. Struggling to deal with demand, many of the watchmakers in each of the cities decided to follow a tried-and-tested business strategy: outsourcing their production. Geneva was the beneficiary, by 1760 boasting approximately 800 masters employing ‘some 4,000 workers in the city’, collectively making around 85,000 timepieces a year.

From the outside, Geneva’s watch making boom looked like a triumph. Inside the city’s workshops, however, the artisans were struggling to keep up. Their solution was to look beyond the city to an unlikely source: the remote mountain villages of the Swiss Jura, where long winters and cheap labor made ideal conditions for production. The Jura’s craftsmen worked longer, earned less, and turned watchmaking into a family trade, eventually outpacing their Genevan counterparts.

Frederic Japy, an entrepreneurial French horologist, introduced an arsenal of specialized tools – bored-arbor lathes, multi-wheel tooth-cutting machines, and bespoke punch presses (a big selling point being that all the machines could be easily worked by children) – paving the way for true mass production in the region, centered around the towns of Le Locle, La Chaux-de-Fonds, and Neuchâtel.

The increase in supply met ever greater demand in the nineteenth century, spurred, in particular, by the standardization of time. In 1847, the British Railway Clearing House recommended every station run on London Time, synchronized to that of the Greenwich observatory – rail travel’s first nationwide clock. Commercial time zones followed in the 1870s, paving the way for global acceptance (bar France) of Greenwich Mean Time as the world’s prime meridian in 1884.

With the advent of cheaper watches, pioneered by American firms such as Ingersoll, which in 1895 brought the first dollar watch to market, ownership spread rapidly. Watch ownership became routine for adult men throughout the western world. As historian Alun Davies has noted, between 1909 and 1913 Britain imported 17 million watches – almost one for every adult male in the country – along with 13 million clocks.

32,768 times per second

By 1870, the Swiss already commanded more than two thirds of the world’s watch output – the first and biggest winners of the new age of time. From 1907 onwards, Swiss watches won first prize in the pocket-watch category every year at the British chronometry competitions at Kew. Their victories built on advanced escapements, a finer class of finishing, and Guillaume balances that shrugged off heat and cold. In 1945, a few decades later, the Swiss accounted for over 80 percent of the global watch market.

Yet just as Swiss watchmaking reached its zenith, a rival technology was stirring: quartz timekeeping, first proven in 1927 by a room-size crystal clock developed by a team at Bell Labs, then refined, miniaturized, and perfected by Seiko at its R&D lab in Suwa, Japan.

A mechanical watch begins with a coiled strip of metal: the mainspring. As the mainspring unwinds, it drives a series of precisely cut gears, transferring energy to a tiny mechanical timing controller: the escapement. The escapement then transfers that power to a weighted balance wheel designed to oscillate at a consistent frequency, the rhythm of which is then used to drive the watch hands. Each swing of the balance wheel releases one gear tooth, turning the mainspring’s uneven energy into steady, even ticks.

It’s an intricate system which evolved over centuries, but one that ultimately involves tiny physical objects bumping up against other physical objects – something that hasn’t really changed since the earliest documented mechanical clocks were installed in the fourteenth century in cathedrals such as St Albans, Norwich, Salisbury, and Wells.

In 1880, however, Pierre and Jacques Curie made a curious discovery: applying an electrical charge to certain types of crystals – in particular, ones made of quartz – makes them vibrate at a very precise frequency. They called this the piezoelectric effect.

In a quartz watch, every movement (watch jargon for the main part of the watch that does the work) contains a piezoelectric crystal, finely cut to oscillate at a specific frequency. (Modern ones are manufactured to vibrate at exactly 32,768 times per second.) The crystal is mounted between two electrodes and sealed in a protective cage to prevent decay.

A battery in the watch passes an electric current through the crystal, triggering the piezoelectric effect. The electrodes detect these vibrations and relay them to an integrated circuit.

Fifteen electronic dividers systematically halve the frequency: 32,768 becomes 16,384, then 8,192, 4,096, and so on, reaching a single pulse to represent one second. The signal is received by a stepping motor, and the screen on your Casio F-91W cycles forward a second.

Millions of calculations occur in a fraction of a second, meaning that quartz watches only lose a few seconds of accuracy each month – versus the seconds-per-day drift even today’s finest luxury watches show – powered by a mass-produced movement anyone can order online for about a dollar apiece (wholesale PC21 quartz movements list from $0.60 each).

For the price of a Toyota Corolla

Back in 1969, when Seiko debuted the Astron, the first quartz production wristwatch, that kind of precision was still exotic and eye-wateringly expensive.

The watch had been decades in the making. First came marine chronometers, then complex multi-instrument systems.

The real prize, however, was a quartz wristwatch. The Swiss had set up an industrial laboratory in Neuchâtel in the 1960s to study the technology, but did not pursue it as doggedly as Seiko.

Although the Astron was 100 times more accurate than any existing watch, it cost $1,250 (just under $11,000 today), about the same as the original Toyota Corolla, launched three years earlier. What would set Seiko apart was the speed with which they innovated over the following decade.

Over the 1970s Seiko slashed power draw dramatically – from about 30 microwatts in the Astronto roughly to 3 microwatts by 1979 – thanks to lower-power circuits and more efficient crystals. It introduced LCD displays; slimmed movement thickness from over five millimeters to less than one and, due to these improvements, was able to cut retail prices to just two to three percent of what the Astron cost. The team also added as much functionality as possible to their watches: calendars, stopwatches, multiple alarms, and calculators. The first two are relatively difficult to incorporate into any mechanical watch. The second two, nearly impossible.

Even worse for the Swiss, Seiko licensed its key quartz patents to other makers, a strategic move aimed at setting global standards, accelerating adoption and cementing Seiko’s lead. The result was a flood of Japanese competitors, most notably Citizen and Casio, both of which launched their first quartz watches in 1974. Buoyed by extremely favorable exchange rates, Japanese watch production tripled during the 1970s, soaring from just under 24 million units in 1970 to nearly 90 million by decade’s end.

By 1977, Seiko had become the world’s largest watch company by revenue, and by 1980, Japan had overtaken Switzerland as the world’s largest watch producer. Between 1974 and 1983, Swiss watch production plunged from 96 million units to 45 million, while employment collapsed – from 89,000 in 1970 to just 33,000 by 1985.

Even the most ardent supporters of Swiss watchmaking were giving the industry its last rites. The year Piguet and Biver launched their brand, historian David Landes published Revolutions in Time, a history of mechanical watchmaking, with a notably elegiac tone:

The quartz timekeeper is a superior instrument in terms of both precision and price, and is bound to win out. Here we have a rare opportunity to study the birth, maturity, and obsolescence of a major branch of manufacture.

One of Seiko’s adverts of the era put it even more pithily: ‘Someday all watches will be made this way.’

A lord of time

In the pre-Quartz era, Omega was synonymous with watches. A key decision to bid on a mysterious and demanding tender from an unnamed buyer in 1962 had paid off: the unnamed buyer was NASA and when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, they were wearing Omega Speedmasters.

Quartz, however, sent Omega into crisis. Instead of choosing either to double-down on mechanicals or fully embrace quartz, Omega tried to do both. The resulting sprawl – roughly 2,000 different references (models) by 1980 – drove sales into a steep decline and prompted key executives to walk out.

One of those was Jean-Claude Biver, a watch obsessive, born in Luxembourg, who had spent time at both Audemars Piguet and Omega. During this time, he developed a theory: Swiss watchmaking could survive only by rejecting quartz and doubling down on high-end, handmade mechanical watches.

Biver knew Omega’s parent company, SSIH, was desperate to offload its dormant assets. So, in 1981, he partnered with Jacques Piguet, whose family firm was transitioning to quartz, to purchase Blancpain, a storied brand that had fallen from selling over 200,000 watches in 1971 to the brink of oblivion. Blancpain cost him 22,000 Swiss francs, about $44,000 in today’s money.

With the acquisition in hand, Biver and Piguet set up shop in a farmhouse in the Swiss mountains. Their strategy was simple: position Blancpain as the ultimate in handmade, human, and artisanal watches, backed by a bold slogan devised by Biver himself: ‘Since 1735, there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be.’

Biver’s philosophy was that watches are not just functional tools but artistic objects, designed not merely to tell the time, but to convey something about the wearer. This idea is now the foundation of the entire modern watch industry. But at the time, it was radical.

Most prestige pieces then marketed themselves first and foremost as tools, a consequence of the fact that it was war, not peace, that drove mass adoption of the wrist watch (as opposed to the pocket watch) among men in the first half of the twentieth century.

The job of a watch was to help you to get things done. The more exotic the watch, the more important the thing you had to do: hence Rolex’s 1950s brand ambassador of choice, General Eisenhower, and its favored class of tagline (example: ‘when a man has the world in his hands, you expect to find a Rolex on his wrist’).

That utilitarian pedigree persisted into the 1980s. Apart from a few slim dress pieces, high-end watches drew prestige from what they could do: survive a saturation dive, time a flight, measure speed with a chronograph. The Rolex Submariner Sean Connery wore in Goldfinger might be iconic, but it was standard military issue for Royal Navy divers at the time. And even if Bond had bought one himself, it would have set him back barely two weeks’ pay.

Biver saw that, in a world where machines were taking over, he could command a premium with the work of human hands. He turned the precision of quartz against itself: ‘That famous quartz precision became of secondary importance. Who cares about ultra-precision to a quarter of a second in everyday life? As a famous Italian retailer explained to his customers: you’re a lord, and a lord doesn’t need the exact time!’

The results came quickly: by 1985, Blancpain had made nearly 9 million Swiss francs in sales and by 1991, that figure had surged to 56 million francs. Compared to the established luxury players these numbers were small. But it was a victory for the emotional appeal of Swiss watches and set a clear course for the future of the luxury watch industry.

Biver had written the playbook and the bigger players emerged from their defensive crouch. In 1985 IWC released the DaVinci; in 1988, Rolex debuted a new version of the Daytona; and in 1989, to mark its 150th anniversary, Patek Philippe unveiled the Calibre 89, then the most complicated mechanical timepiece ever made.

Calling Mr Hayek

This pivot to luxury, however, came at a cost. In Biver’s world, Swiss watchmaking had to make a choice: embrace the luxury market or pursue volume instead. Choosing the former – shrinking product lines, raising prices, and focusing on craft above all else – would allow a few survivors to carry on in the new world of quartz, but at the cost of accepting that the heyday of Swiss mass watchmaking was over.

The problem, however, was that by the time Biver and Piguet arrived on the scene, most of the watch industry had been moving in the opposite direction, clustering into two sprawling holding groups. SSIH controlled Omega, Tissot, and Lemania; ASUAG specialized in parts and movements but, to protect its customer base, had spent much of the 1970s hoovering up dozens of mid-tier brands. Independent houses such as Rolex, Patek Philippe, and IWC stayed outside these blocs.

Together, these two companies employed over half of the watch industry’s remaining workforce. They were also technically insolvent, surviving instead only on emergency credit lines from a consortium of Swiss lenders. By 1982 those creditor banks decided it was time for an exit plan, so they jointly hired Lebanese-born consultant Nicolas Hayek to tell them whether to liquidate, merge, or attempt a turnaround.

Hayek began his corporate life at Swiss Re, one of the world’s largest insurers and reinsurers, before setting up his own firm, specializing in engineering and supply chains. He was very good at it: by 1979, Hayek Engineering had over 300 clients in 30 countries, including the Swiss Army, putting him firmly on the banks’ radar. When the call came to advise, Hayek accepted. If you were to pick a businessman as philosopher, you’d struggle to find a finer example than Hayek. He loved building things and believed that a country that couldn’t build, frankly, was no country at all: ‘We must build where we live. When a country loses the know-how and expertise to manufacture things, it loses its capacity to create wealth – its financial independence. When it loses its financial independence, it starts to lose political sovereignty’.

Hayek saw the choice between luxury and volume as a false dilemma. If a country couldn’t produce everyday goods in a category, it would eventually lose the ability to make the luxury ones too.

Here was the perfect chance to prove his theory: beat the Japanese at mass production, in Switzerland, a country then among the highest-wage nations in the OECD. So instead of breaking up the companies, Hayek proposed merging them into a single entity.

Both boards eventually agreed, and the Swiss competition authority raised no objection, so in 1983, the two firms were folded into a new holding company, the Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking (SMH). Hayek was installed as chairman.

Before Hayek, SSIH and ASUAG followed a simple model: thousands of semi-independent workshops made components while the parent conglomerates handled marketing and distribution. It was a system unchanged since the first watchmakers of the Jura, when families built watches at home and salesmen carried them over the mountain passes to sell to the world.

To Hayek, this was completely backward. It led to inefficiencies and uncompetitive costs on the production side and to undifferentiated brands that tried to be everything and ended up as nothing.

Manufacturing was progressively pulled into a handful of high-capacity ETA plants, chiefly those based in Grenchen and Fontainemelon, while brand workshops that once made their own calibers were refocused on design and marketing. Lines were automated: CNC-machine-milled main plates, material transport conveyors, and rotary presses looked on as plastic cases were welded in a single pass.

Standardization followed. Watches across the group now shared the same Micro Crystal tuning forks, Renata silver-oxide cells, and workhouse movements like the ETA 2824-2. Even the most prestigious brands in the group’s stable – Omega, Longines and Rado – were no longer permitted to produce their own movements. In many cases, they were forced to rationalize their lines. The effect was dramatic: Omega cut its catalogue from 2,000 references to 1,000, then to just 130 models within five years, and production costs fell and reliability jumped.

Secondly, marketing was radically decentralized. Each brand was given a clear segment of the market, and its job was to dominate that segment. The center’s only role was to defend each brand’s differentiation.

But there was still a missing piece. In his 1982 report, Hayek split the global watch market (roughly 500 million units per year) into three tiers: low, middle, and high. The low tier, according to Hayek, watches priced up to $75, made up 90 percent of the market. None of those 450 million watches were Swiss-made.

To do that, the Swiss needed a brand that could out-quartz the quartz.

A jewelry store in Texas

If you stepped into a jewelry store in Dallas, Texas, in the run-up to Christmas 1982, you’d find something unusual. A simple watch, probably black or dark green. No clamshell case – the hallmark of watch sales at the time – but instead, a plastic cover. And a price tag of just twenty dollars.

In 1978, ASUAG’s board merged several parts and movement companies into a single entity, concentrating watchmaking talent under one roof. They called it ETA. Within a year, its micro crystal division became the first in Europe to mass-produce quartz blanks: rare good news in a time of crisis.

The same engineers then took on a publicity challenge: build the world’s thinnest watch. Launched in 1979, the first Delirium was just 1.98mm thick – a marvel of Swiss engineering. But at $5,000 (about $25,000 today), it was no savior of the Swiss watch market.

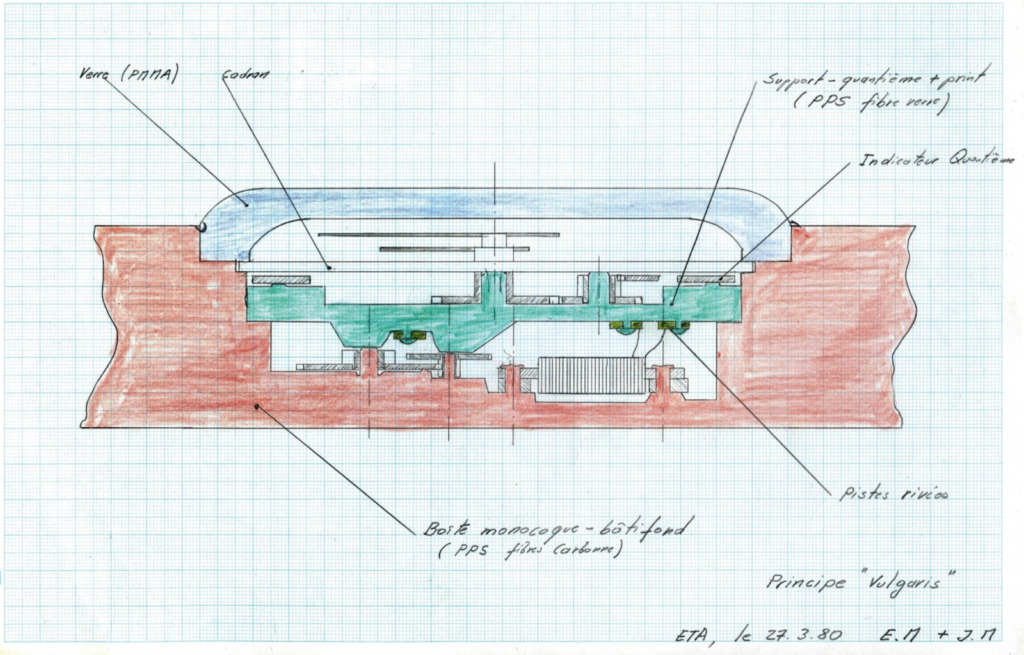

The Delirium team made radical manufacturing decisions, most notably eliminating the bottom plate of the movement and integrating parts directly into the caseback (the rear cover of the watch that normally just seals the internals). Ernst Thomke, ETA’s managing director realized the same one-piece architecture could be applied to a mass-produced watch as well.

He set up a separate R&D team to pursue a plastic, mass-molded version. But progress was slow. At the same time, however, two other ETA engineers, Elmar Mock and Jacques Müller, had been working on an off-the-books prototype of their own. But they were limited by technology: they needed an injection molding machine – at a cost of 500,000 Swiss francs (around $1,000,000 today).

Without authorization, Mock placed the order. Thomke called him in that same day. The meeting was at 1pm – meaning Mock, who found out at 11am, had two hours to save his job. Working fast, he and Müller sketched out a design. In the meeting, instead of resigning, Mock went on the offensive – pitching his unauthorized purchase as a necessary step in creating a new, inexpensive plastic watch.

Shortly after, Mock was stripped of his regular duties, as was Müller. They weren’t fired, but instead reassigned, tasked with developing their new prototype in secrecy. By December 1980, they had hand-assembled five working prototypes. The injection-molding press still hadn’t arrived.

Their prototypes took the Delirium’s approach even further, using ultrasonic welding to build the mechanism directly into the watch’s plastic case. The result was a radical simplification. Instead of the usual 91 parts found in quartz watches at the time, the new watch had just 51, each of which could be inserted from above by a machine, perfect for mass production. It was three times cheaper to produce than any other Swiss-made watch, and could be assembled in a matter of seconds.

The team called it the Vulgaris. We know it as the Swatch.

Fashion that ticks

When Hayek arrived, Thomke quietly revealed what his team had built: an inexpensive Swiss-made quartz watch that could put the industry back into all three market segments: the final realization of Hayek’s original vision. The watch launched in March 1983, and soon after, it took off, a true Swiss-made alternative to Japanese quartz.

The impact was immediate. By 1985, Swiss watch production had surged from 45 million units to 60 million. By 1992, ETA had produced its 100 millionth Swatch; three years later, its 200 millionth. Before Swatch, the idea that the Swiss could mass-produce a watch for under $50, while still turning a profit, was a fantasy. Swatch made it a certainty.

Swatch, in particular, wasn’t just an innovation in process. It was a revolution in design and marketing. Only when Swatch fully embraced color and self-expression did the product take off. As one designer put it: ‘What we were selling was fashion that ticks.’

Few can match Swatch in its early years when it comes to marketing. In 1984 alone, Swatch hosted the world’s first breakdancing championship, launched the first national hip-hop tour, debuted its first artist collaboration, and hung a 13-ton Swatch off the side of Frankfurt’s Commerzbank building.

Swatch’s real importance wasn’t in dominating the lower end of the market (Swiss watch revenues remain extremely top-heavy to this day), but in giving Swiss watchmaking its confidence back.

The Carnaby Street Mob

It took half an hour for the police to arrive on Carnaby Street. Some in the queue had been waiting for over two days, setting up tents and chairs outside the shop as soon as Swatch announced its latest release, a collaboration with Omega based on the iconic Speedmaster that Armstrong and Aldrin had taken to the moon with them all those years back.

The design was nearly identical, except for one detail: instead of metal, it was made from a Swatch-developed eco-plastic. The price, however, would have made Thomke proud: just £240, more than seven thousand pounds cheaper than its Omega-made sister. They called it the MoonSwatch.

At 9am on 26th March 2022, the doors opened and the queue became a mob. In the weeks that followed, the same scenes played out across the world, from New York to Tokyo, from Milan to Singapore. Thousands of people fought for something that they, in a world where 95 percent have a smartphone, no longer needed to tell the time.

It’s easy, with hindsight, to mock predictions like David Landes’s. But, ultimately, he was right: Swiss watchmaking should have died with quartz, along with the lamplighters of Victorian London, the ice harvesters of New England, and the telegraph operators of Western Union. Instead, Biver, Hayek, and the watchmakers of Switzerland found a way to outlive their own obsolescence – not by competing on function, but by redefining value.

Biver doubled down on the human touch: craftsmanship, heritage, and emotion. His approach became the blueprint for the largest watch companies of today, as well as the new wave of independent artisans. In 1996, Patek Philippe launched its iconic advertising campaign: ‘You never actually own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation.’

Hayek took the other approach: embracing the new technology, re-engineering everything from the ground up, and applying it to a changed world. It was the same approach picked up by Apple when it launched the Apple watch in 2014. Once again watches had a function – not just as a timepiece, but as a medical device.

There is room for both approaches. Apple and Rolex, at time of writing, now jostle for the top spot as largest watch company by annual revenues. Full functionality or full artistry. Take your pick.

Things came full circle when, in 1993, SMH acquired Blancpain and Hayek handed Biver his toughest challenge yet: reviving Omega. After Omega, Biver moved to Hublot, led TAG Heuer, and took charge of LVMH’s watch division, before retiring, only to unretire soon after. ‘Who can retire from a passion?’ he said in a recent interview. He now owns an independent watch company with his son.

Hayek became something of a celebrity in Switzerland. He died in 2010 in his office, still working. Shortly before his death, he was voted by the Swiss public the sixth greatest son of Switzerland.

Like the watchmakers of the Jura before him, Hayek turned SMH into a family business: his son now runs Swatch; his grandson, Blancpain. Walk into one of Swatch’s 3,400 stores today and you’ll likely see their follow-up to the MoonSwatch in the front window: a Swatch-made recreation of Blancpain’s most famous watch, the Fifty Fathoms.

Today, Swiss watchmaking is a $30 billion business, with a near monopoly on luxury manufacturing. The country ships just two percent of all watches made each year, yet that sliver captures almost 45 percent of all revenue from watches worldwide. An industry that once faced extinction is stronger than ever. Some things survive not because they have to, but because we want them to. Instead of causing the end of Swiss watchmaking, the Quartz Crisis was the moment it was reborn.