Europe’s cutting edge firms are falling far behind the American frontier because of restrictive labor laws.

In recent decades, Europe has fallen behind the United States. In 2000, incomes in the original six members of the European Union were just 10 percent behind Americans. Today, they are 20 percent lower. One factor behind this has been the lack of innovation in European business. To a striking extent, Europe lacks tech giants like Google, Meta and Amazon. But even in industries in which it has traditionally excelled, like carmaking, Europe has failed to keep up. Tesla is now worth more than the next nine largest carmakers in the world put together. Six American cities are now served by robotaxis made by Waymo. Understanding why Europe doesn’t have Google is important. Understanding why it doesn’t have a Tesla is existential.

There are many partial explanations: high energy prices, expensive housing, excessive proceduralism, high taxes, extractive interest groups, and politicians with a penchant for degrowth. But all of these problems are true of California as well, which is nonetheless home to Waymo and birthed Tesla before it moved its headquarters to Texas in 2021. Explanations often blame Europe’s lack of research spending, but governments spend more on research in Europe than in America. And just seven companies globally – Google, Apple, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Samsung, and Huawei – spend more on research each year than Volkswagen.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

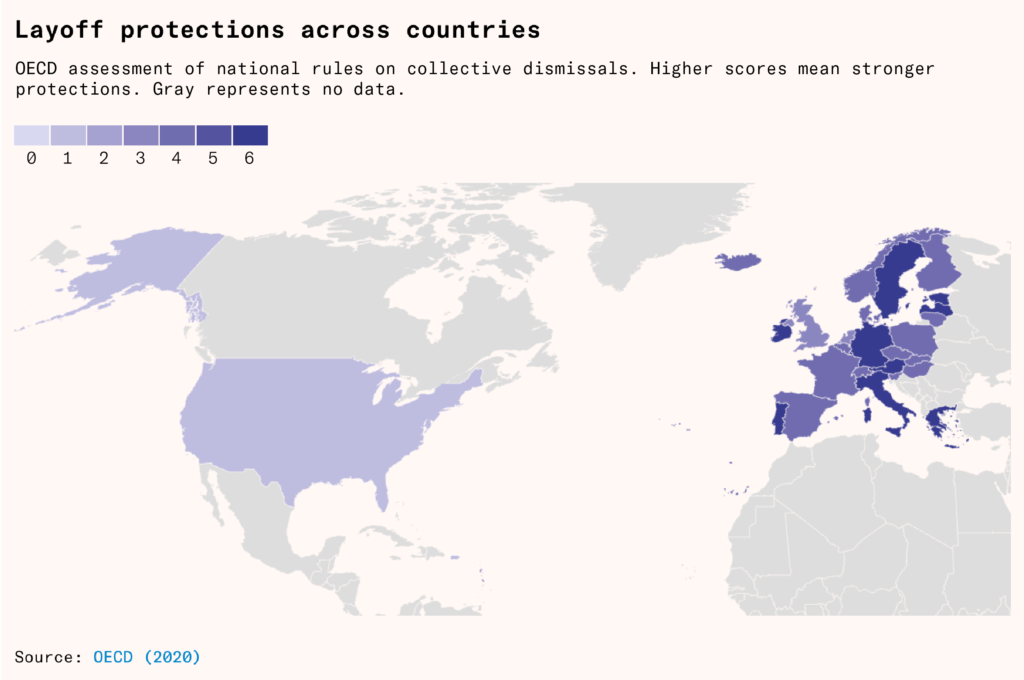

What really sets Europe apart from states like California is different. Relative to income, it costs large companies four times more to lay off Germans and French than American workers, a difference arising entirely from different regulatory approaches. As a result, it virtually never happens: Americans are ten times more likely to be fired than Germans in any given year. In this respect, the European economy differs greatly from the American one. By American standards, a European business has to be exceptionally confident that it will want an employee for a long time before hiring them.

This may sound like a great virtue of European life, and in a way it is. But it has costs. If it is expensive to fire people, then companies may pay them less in order to balance out employment costs, or they may not employ people at all. To understand the innovation gap, however, there is a third effect that is even more important. If it is expensive to lay people off, employers avoid creating jobs that they might subsequently discontinue. Innovation involves experimentation and risk, so jobs in innovative areas of the economy are more likely to be discontinued than jobs elsewhere. High severance costs create a fundamental incentive for European businesses to avoid innovative areas and concentrate on safe, unchanging ones. In the long run, this is a recipe for decline.

Europeans are attached to their secure jobs, and understandably so. But they may be able to get most of the benefits of the American model without adopting it wholesale. Some smaller European economies have adopted ‘flexicurity’ models that protect their citizens from economic insecurity without disincentivizing innovation. Building a European Tesla requires institutional reform, but it does not require giving up what Europeans value most about their regulatory settlement.

Failure costs

All businesses make mistakes. Dismantling these failures often means shedding physical assets: writing down investments and breaking factory leases. But for many companies, most of the cost of failure comes from making employees redundant. These payments are large even in countries with laissez-faire labor rules like the US: when Google restructured in 2023, it spent $2.1 billion laying off 12,000 workers, about $175,000 per person. Its second largest expense, breaking office leases, was $1.8 billion.

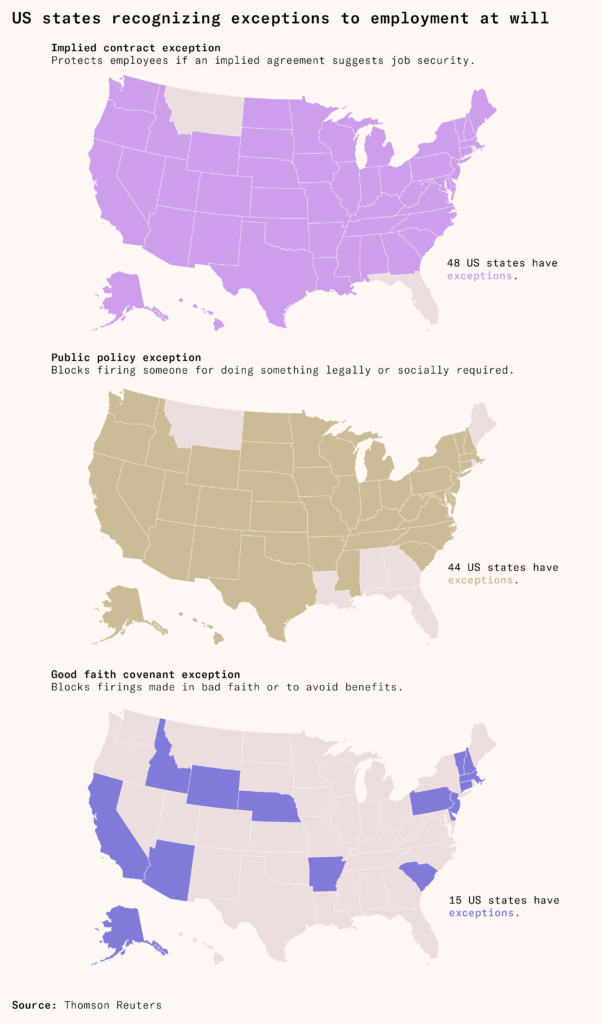

But however costly firing is in the US, it is much more expensive in Europe. US labor market legislation is liberal by global standards. American states tend to recognize a mix of three exceptions to employment at will: the public policy exception, which prevents workers from being fired for fulfilling duties such as appearing on a jury; the implied contract exception, which prevents firings if there is an implicit agreement that abrogates that right; and the good faith exception, which prevents firing an employee to avoid incurring a new obligation, such as stock that is about to vest. Beyond that, and the constraints of anti-discrimination rules, the American employer can usually release an employee immediately, for no cause at all.

Some American employers offer more generous redundancy packages, like Google in the example above. But this happens because American businesses want the concessions that they extract in exchange, such as non-disclosure and arbitration agreements, as well as appearing more attractive to potential hires. Neither the Department of Labor nor most state governments actually require it.

The opposite is true in most European countries. Severance payments are often mandated by law and are much larger than in the US. In Germany, a worker who is fairly dismissed due to business needs is entitled by law to 15 days of pay for every year they have spent with the employer.

Getting as far as making these severance payments can be a challenge for German employers. Under the Protection Against Dismissal Act, the Kündigungsschutzgesetz, redundancies over ten employees must pass a social selection test (Sozialauswahl). Employers cannot choose who leaves: they must rank employees by age, years of service, family maintenance obligations, and degree of disability, and then prioritize dismissing those with the weakest social claim to the job. If someone is dismissed for operational reasons but the company posts a similar job elsewhere, the dismissal is usually invalid.

Disabled employees can be dismissed only with the approval of the Integration Office (Integrationsamt), a public body. The office will weigh the employer’s reasons, whether they have taken sufficient steps to integrate the employee, and whether they could be redeployed elsewhere in the organization. Workers who also become caregivers cannot be dismissed at all for up to two full years after they tell their bosses they fulfill that role.

As a company becomes larger and tries to let more workers go at once these difficulties increase. In many European countries, companies with more than a certain number of workers – 50 in the Netherlands, 5 in Germany – are obliged to create a works council, which represents employees and, in some countries, must give its approval to decisions the employer wants to make regarding its employees, including layoffs or pay rises or cuts.

Works councils have stopped some of Europe’s largest companies from making changes. In 2024, Volkswagen’s works council blocked the company’s plan to cut costs by closing three factories in Germany. After the company union organized ‘warning strikes’, Volkswagen agreed to keep its factories open and halt compulsory redundancies until 2030.

Companies that are allowed to fire someone and can afford to pay the severance costs have to wait and pay additional fees. Collective dismissal procedures in Germany start after 30 departures within a month; once triggered they require further negotiations with the works council, a waiting period, and the creation of a ‘social plan’ with more compensation for departing workers. When Opel shut down its Bochum factory in Germany, it reached a deal with the works council to spend €552 million on severance for the 3,300 affected employees. This included individual payments of up to €250,000 and a €60 million plan to help workers find new jobs.

French law requires any restructuring involving more than ten employees in a month, even if they work in different parts of the company, to be approved by a special regulator and reviewed by the works council in two meetings over multiple months. It is only allowed after a ‘good faith’ attempt to protect the jobs of the workers involved (by attempting to give them jobs elsewhere in the company, keep them on part-time, or induce other companies to hire them). To prove that financial conditions justify the layoffs, French companies often impose hiring freezes across the company when employees in one division are let go.

If a court determines that a company that has laid off employees was not in a financial state to merit laying off workers, that court has the power to reclassify the dismissals as unfair and impose even higher severance as a fine. Continental, a tire company, tried to shrink its French workforce during the financial crisis. A court decided that there was a ‘lack of economic justification for the dismissals in light of the overall situation and results of the global Continental group’. The company was obliged to pay up to three years of salary to the 680 employees involved.

These rules – severance, negotiating periods, works councils, buyouts, and waiting periods – collectively impose high costs on a European company that tries to let workers go. The costs of restructuring are so high that companies will often try and bribe their workers to leave. In 2023, Amazon offered French employees a year’s salary to leave voluntarily so they didn’t have to fire them and go through a legal restructuring. In 2024, German chemical manufacturer Bayer offered long-tenured workers 52.5 months of pay, or over four years’ worth, in exchange for quitting.

According to a rough estimate by Olivier Coste and Yann Coatanlem, a corporate restructuring in Germany and France costs companies the equivalent of 31 and 38 months of salary per employee laid off, putting all of the above costs together. In Italy, this is 52 months. In Spain, it is 62 months. In the United States, the cost per employee is just 7 months.

It is widely understood that Europe’s restrictive labor laws involve tradeoffs in exchange for the additional security they give to workers. The standard story is that these rules lead to lower wages, when employers can negotiate wages directly with individual workers, or lower employment levels, when companies have to bargain with workers en masse and cannot just price the cost of firing them into wages. But Europe’s stagnation, especially in the north, has ceased to be primarily a problem of unemployment. In the Euro area, about 71 out of every 100 people of working age have a job. This is nearly the same as in the United States, where about 72 out of 100 working-age people are employed.

Rather than reduce hiring in response to more expensive firing, companies in Europe have shifted activity away from areas where layoffs are likely. European workers are for sure, solid work only. This works well in periods of little innovation, or when innovation is gradual. The continent, however, is poorly equipped for moments of great experimentation.

Risky business

Building self-driving cars has involved lots of failures. Apple spent $10 billion on its self-driving car project, before scrapping it and never transported a single paying customer. General Motors acquired Cruise, an autonomous taxi company, for $1 billion in 2016, only to close it down in 2024. It had sold just $102 million worth of rides in 2023, making a loss of $3.4 billion that year.

But failures like these are unavoidable in pursuit of innovations that succeed. Waymo is estimated to serve a fifth of the San Francisco ride hailing market, and, as of April 2025, carries a quarter of a million passengers each week in five cities. Uber and Lyft, which had halted their self-driving cars in 2020 and 2021 after years of losses, have partnered with Wayve and Baidu to offer autonomous alternatives to Waymo and the Tesla cybercab.

For both American and European companies, the upsides of success from bets like these are similar. But the downsides from failed bets are much greater for Europeans. On top of the lost investment, many European companies also face significant severance costs, negotiations with worker representatives, requirements to redeploy unneeded workers internally, and the need for permission from regulators to approve layoffs.

In 2018, Audi launched the Q8 E-Tron, a fully electric SUV. As bets go, the E-Tron wasn’t even that bold: Porsche, Jaguar, BMW, and Volkswagen would all announce major electric models that year.

Unfortunately, the E-Tron saw weak sales, and it was cancelled in 2024. The factory where it was built, Audi Brussels, was to be closed. But instead of just writing off the plant, as an American company would have done, Audi had to set up a huge scheme to pay departing workers. After months of negotiations, Audi agreed to spend €610 million on severance, or over €200,000 per employee. These payments to employees more than doubled the costs of closing the car factory, costing more than writing off all its assets.

A luxury electric SUV may still turn out to be a good idea, and Audi may still be the company that will make the best one. But Audi executives have learned their lesson. A future E-Tron, they have indicated, will be built at a plant in Mexico.

Failure costs lead some European companies to try and avoid having to innovate altogether. For years, the German car industry refused to see that the writing was on the wall for traditional cars powered by an internal combustion engine. In 2013, Martin Winterkorn, then CEO of Volkswagen, dismissed the idea that electric cars could be suitable for long-distance travel. Instead of seeing this as a temporary limitation that would one day be solved by better batteries or more charging infrastructure, the company simply ignored electric vehicles for the next five years.

After years of delay, Volkswagen did decide to pivot. In October 2018, its new CEO Herbert Diess predicted that by 2020 the company would produce electric vehicles that ‘can do everything like Tesla and are half the price’. The vehicle to meet this ambition was the ID.3, so named as it would mark a symbolic ‘third era’ for the brand, after the Beetle and the Golf. Volkswagen threw $50 billion at its electric car line-up, making them some of the most costly cars in history, Unfortunately, it failed again.

In part, this was the product of complacency. Volkswagen’s leadership, made up of traditional automotive executives, saw software as an inferior artform to traditional manufacturing. They committed to highly ambitious public timelines and to developing all software in-house. The company’s in-house software team was short-staffed and struggled to meet demand. As one insider put it at the time: ‘It’s an absolute disaster’. In the months leading up to the launch, the team was finding up to 300 new bugs a day.

It was also the product of a company that has been unable to allocate and reallocate workers effectively for decades. Since 1994, Volkswagen has guaranteed German factory jobs at the company – the result of a negotiation with the union where, rather than firing people, the company cut costs by switching to a four-day workweek, an arrangement which was in force until 2006. The result has been that, for the past three decades, being hired has effectively resulted in a lifetime appointment.

In June 2024, Volkswagen admitted defeat and set up a joint venture with American electric vehicle startup Rivian. In exchange for an investment of up to $5 billion, Volkswagen received immediate access to Rivian’s software for use in its own cars. In essence, Volkswagen has had to license core technology from a small American rival because it has found innovating so hard.

Herbert Diess, the CEO brought in to lead the transition to electric vehicles, would not be there to see it. His clashes with the works council over factory closures and his frequent warnings that Volkswagen was falling behind Tesla caused him to run afoul of the Porsche and Piech families that own a majority of the company. He was fired in July 2022.

Europe’s recent history is littered with examples of great companies that failed to adopt the next innovation. Nokia built its first smartphone in 1996, developed a prototype of a phone with a touch screen and internet connection around the turn of the millennium, and would eventually release early touch screen devices. However, it never developed the software needed to make it successful.

It is not surprising that Nokia was unwilling to incur more risks, given the costs it faced when it did restructure. In just one year, 2012, Nokia spent €1.8 billion to reorganize its phone and telecommunications business, a sum which consisted ‘primarily of employee termination benefits’. While it is not possible to infer how much they spent that year per employee, when the company closed a mobile phone plant in Germany, in 2008 it spent €200 million to fire just 2,000 employees.

Innovation requires huge, uncertain bets. European companies can and do invent, as Nokia once showed, but they rarely take repeated risks the way American superstars do.

This explanation fits other problems in Europe as well. The problem with European venture capital is often thought to be insufficient supply of capital. But if the downside of failure is high, returns are also lower, making it unsurprising that less is invested. An estimate by Coste and Coatanlem shows that the median internal rate of return, a measure of profitability, between 1998 and 2022, of venture capital firms in Europe was around five points lower than in the US, evidence that fits the view that Europe’s investors are spending less due to a lack of opportunity, not capital.

Keeping small business small

Great innovation often comes from new companies, not old ones changing course. Tesla leads the way on electric vehicles, not Ford, General Motors, or Chrysler. National politicians in European countries are aware of the downsides of their labor laws, and usually exempt small companies and startups from them. In particular, the rules governing collective redundancy often only apply to companies above a certain size and making a large enough number of redundancies.

But the purpose of a startup is to grow. When a company does succeed it is governed by the rules covering large companies, hurting its ability to grow beyond a few hundred employees. It also damages acquisitions, as any acquiring company is governed by employment rules, and is similarly deterred from taking bets that involve hiring.

As a result, acquisitions are rarer in Europe. Between 2012 and 2016, 79 percent of all startup acquisitions tracked by Crunchbase took place in the US. Of those that did take place in Europe, 44 percent were acquired by American companies. European companies made just seven percent of acquisitions of American startups.

Many companies with potential choose to leave. Companies like Grammarly and Hugging Face were once headquartered in Europe. Bird, a messaging company, was until recently one of the Netherlands’ most successful start-ups. In 2024, employees complained that it had long breached the legal threshold for establishing a works council: 50 employees. To avoid complying, its billionaire founder moved the company to New York, Singapore, and Dubai. According to one estimate, 11 percent of US tech startups have a European co-founder: it is just not the case that Europeans are not entrepreneurial enough. Europe’s problem is that they choose to be entrepreneurial somewhere other than Europe.

When the rubber leaves the road

With government seats on the board, a jobs guarantee, a works council, the Sozialausgleich, and the Sozialplan, Volkswagen seems like it should have never succeeded. But the European model works well for incremental innovation, which dominated manufacturing in the decades after the Second World War.

For over a century, making better cars has in large part been a question of making existing designs more efficient. A 1975 Volkswagen Polo (the first) and a 2025 Volkswagen Polo (the latest) both share the same basic powertrain, a piston-driven combustion engine, but the latter accelerates twice as fast and is a third more fuel efficient.

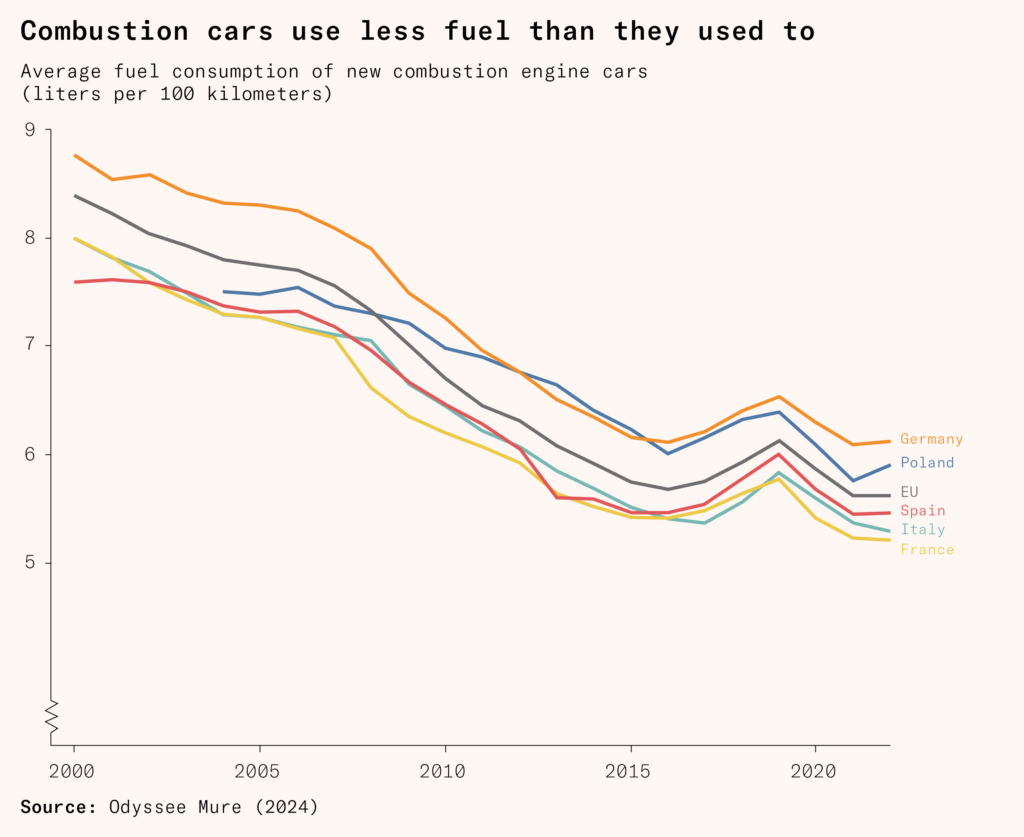

Europe’s newest internal combustion engines are engineering miracles. Volkswagen squeezes roughly the same horsepower from their latest one liter engine as Packard could get from an engine five times its size 90 years ago. The average fuel used per kilometer by new combustion cars sold in Europe has decreased by a third since the turn of the twenty-first century.

Even weaker manufacturers like Renault have long left their American competition behind when it comes to efficient petrol and diesel engines. And, remarkably, these improvements have happened almost every single year, as European automakers brought out cars that were slightly better than the previous generation.

Europe’s labor laws are supposed to help find those efficiencies. Companies can make deeper investments in workers because the costs are amortized over long tenures. All German manufacturing workers train twice: once as an apprentice at a school, and then again at a specific company, a system known as duale Ausbildung. The average age of an employee at Volkswagen is 45, and only 0.1 percent of German employees will be fired in a given month, compared to 1 percent in the United States. Rules that can seem strange to foreigners make more sense from this perspective.

Europe’s companies have immense, specialized knowledge. The problems happen when radical innovation is needed, as in the shift from gasoline to electric vehicles. The great makers of electric cars have either been new entrants, like Tesla and BYD, or old ones who have had their insides stripped, like MG. Even where a European carmaker has been central to the rollout of a major new technology, as with Jaguar making Waymo’s taxi fleet, it underscores Europe’s weakness: the vehicles were manufactured at a plant in Austria, but then shipped to Arizona to be outfitted with Waymo’s autonomous driving technology. Now that prior expertise is not as useful, and succeeding at cars means taking big bets on new ways of doing things, the rigidity of Europe’s labor laws has led its car companies to run out of road.

The best of both

If Europe wants a Tesla, or whatever the Tesla of the next decade will turn out to be, it will need a new approach to hiring and firing. Many Europeans fear that this cannot be reconciled with Europe’s ‘social model’: the desire to give workers certainty and protect them from the vagaries of the business cycle.

But there are examples of European countries having it both ways. In Austria, workers have a portable savings account, the Abfertigung Neu, that pays their severance and is funded through employer contributions, which reduces the costs of restructuring to an employer. Switzerland maintains (relatively weak) works councils and a generous public safety net, but has no mandatory severance. Denmark uses a flexicurity model where employers can almost fire at will, but workers can draw on generous unemployment insurance which covers up to 90 percent of their previous income for two years. In exchange for reduced job security, the Danish government spends two percent of GDP on subsidies and other incentives for retraining and rehiring the unemployed.

While it may be difficult to imagine a France or an Italy giving up their labor market protections, the point of all of these models is to protect workers’ incomes against the capriciousness of capitalism. Most European countries do this by forcing companies to hold on to their workers except in extreme circumstances; in Denmark, Austria, and Switzerland, the government bears that cost. Europeans are unlikely to embrace the American model, but they might accept the Danish one.

Europe’s most flexible economies are its most innovative. Denmark and Switzerland have given the continent Novo Nordisk, Roche, Nestlé, and Novartis. The small and few countries that have adopted a flexible model are Europe’s innovation heavyweights. (Meanwhile, the countries with the strictest employment protection, like the Spaniards and the Italians, are some of the worst, by this measure.)

If more European states do decide to change their labor markets, the exact policies they adopt may not be Danish-style flexicurity, but it will need to use some of its principles. Since innovation is primarily a function of elite talent rather than the median worker, even limited reform could deliver many of the same benefits. Perhaps only workers above a certain income threshold could face Danish labor rules. Even allowing all workers above the 90th percentile of income to opt out of employment legislation would make German services very competitive with the American market, since German workers at the 90th percentile in 2022 earned about $80,000 per year in today’s money before tax. (The equivalent in the US was about $147,000.)

Europe had Teslas once

Until the nineteenth century, many continental labor markets were still governed by the feudal system. As everyone knows, feudal serfs could not leave the service of their lords at will. But it is often forgotten that this went both ways: serfs came with the land, and although feudal landowners had many powers over them, they generally did not have the right to turn them out. Employer and employee were stuck with each other, even if both would be much better off terminating the arrangement. As Enlightenment reformers such as French Minister of State Anne‑Robert‑Jacques Turgot and Habsburg Emperor Joseph II pointed out, this arrangement was inefficient. Workers were hindered from moving to more productive employers, regions or sectors, while landowners were hindered from agricultural restructuring or innovation that conflicted with tenants’ rights.

It would be only a little fanciful to describe Europe’s current system as ‘one-way feudalism’. Employees have the right to leave their employers, just as they do in all free societies. But employers have only a tightly circumscribed right to leave their employees. As we have seen, the costs of doing so are so high that European employers have to a large extent stopped doing so.

Europe’s current system may seem like a deep feature of its culture, inherited from the feudalism of its past. But, for more than a century between the end of Enlightenment and the Second World War, European companies innovated furiously, like American ones do today. In the 1880s, the French company De Dion-Bouton became convinced that the future of transport lay in automobile vehicles. It invested heavily in steam-powered automobiles. ‘Steam cars’ could theoretically go up to 35 miles per hour, but they took about 30 minutes to start and needed a full time stoker to keep going. In 1894, De Dion-Bouton gave up and discontinued its steam car experiment.

But the story didn’t end there. De Dion-Bouton made a second attempt, using experimental petrol engine technology instead. This time, it worked. De Dion-Bouton’s production grew exponentially, and by the early 1900s it was the world’s largest automaker, employing far more people in petrol car production than it ever had for its steam line, and germinating one of the key inventions of the twentieth century. Europe does not have Teslas today. But it has had them in the past, and, without giving up what Europeans value about their economic model, it could have them again.