Building a state is not a matter of copying first world institutions. It is a tough process of deals and compromises. 19th century Mexico is a good example.

We are impatient. We want quick results. We look to others who have made it to try to copy what they do, but often find out the hard way that it isn’t as easy as it seems.

We have that same impatience when it comes to the development of economies and government as well. Maybe it was hard in 1800 when almost all countries were poor and undeveloped. But in 2023, there are a plethora of examples to follow. Why can’t poor countries just mimic the common characteristics of rich countries and skip over all the toil and trial and error of the middle part?

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock coined the phrase ‘skipping straight to Weber’ to refer to situations where international financial institutions like the World Bank or the IMF urge poor countries to catch up to rich ones by mimicking their institutions instead of recognizing that these institutions typically emerge only after a long process of trial and error. State development is difficult because it requires pushing in the right direction while constantly making win-win deals with existing power brokers at the temporary expense of the rule of law and impartial justice.

Very few people understand how difficult it was to build state capacity in the past. Others conclude that things like property rights, state capacity, and development happened easily, quickly, and automatically, and they can’t figure out why developing countries are having so much trouble. Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto spent 13 years visiting land registries in rich countries, asking the experts that worked there how their respective countries created functional systems of property rights. None of them knew; they all admitted to never having thought of the question.

While De Soto was focused on property rights, in this piece we will examine the development of state capacity in Mexico. There are lots of definitions of state capacity, but here I mean the ability of the Mexican government to enforce the laws in all of its territories, to be able to tax its people, and to formulate and enact policies. Not only does nineteenth century Mexico have all the ingredients for a good story, it also shows that some of the ways that countries do finally develop and governments build the capacity to rule are ones that no international financial institution would ever recommend.

The chicken and egg problem

Building state capacity is a collective action problem. Even though all individuals may benefit collectively, and even though each individual may favor the end goal, each individual’s personal incentive is usually to free ride on efforts to build an effective state. The only way to solve this problem is having the money and the power to both punish and reward.

However, this is a chicken and egg problem. The ability to punish opposition and pay government salaries depends on having tax collectors who can collect taxes, and a military or police force that has a monopoly on violence. In order to have a comparative advantage in violence, a ruler must be able to at a minimum pay military salaries. But to pay these salaries, the ruler must also have the ability to tax citizens, which of course relies on force. And if military officials are self-interested, why don’t they overthrow the ruler and get access to the tax revenue? It is a circular and thorny problem.

The Mexican context

Mexico in the nineteenth century presents a dramatic example of this problem. Mexico suffered extreme political instability and strife in the nineteenth century. There were 800 revolts between 1821 and 1875. Between independence in 1821 and 1900, Mexico had 72 different chief executives, meaning that the average term was only a little more than one year long. Likewise, the country had 112 finance ministers between 1830 and 1863. In addition there were several invasions and secessionist movements.

The country also experimented with several different forms of government, including two empires (one headed by a French-backed, Austrian-born member of the Habsburg dynasty), one disputed period where there were presidents from both main parties, four republics, one provisional republic, and a long dictatorship. President Guadalupe Victoria was the first constitutionally elected president of the country, and the only one who would complete a full term in the first 30 years of independence.

Some other examples: There were four Mexican presidents in the years 1829, 1839, 1846, 1847, and 1853, while there were five in 1844 and 1855 and eight in 1833. Antonio López de Santa Anna, who was President of Mexico on ten separate occasions, was president four different times in a single year.

Mexico faced constant challenges to its sovereignty in the first 50 years of independence, from the secessions of Texas and Central America, to the secession attempts of the Yucatán, as well as numerous smaller rebellions.

And the threats were not all internal. Mexico lost one-half of its territory to the US in the mid-nineteenth century, an event that caused many Mexicans to lose even further respect for their government. In 1847, Mariano Otero, a leading Mexican jurist and utopian socialist of the period, explained its failure to resist US forces as being down to the fact that ‘Mexico did not constitute, nor could it properly call itself, a nation.’

It wasn’t until the Porfiriato (1876–80 and 1884–1911), the period of time when Porfirio Díaz was president/dictator of Mexico, that the Mexican state began to have some capacity to fund policies and keep a lid on revolts against the central government. When Díaz first took power, there were still only five banks in Mexico, almost no manufacturing, and only 400 miles of railroad, in a country more than three times the size of France – which had 37,000 miles of track at that time. For 71 of Mexico’s miles, the trains were pulled by mules rather than steam engines.

After decades of stagnation, federal revenues actually increased by five percent a year between 1895 and 1911, and this was the time when the Mexican economy began to grow. During Diaz’s tenure, manufacturing and oil production took off, banking became much more developed, and 17,000 miles of railroad tracks were laid, connecting all of Mexico’s largest cities.

These were revolutionary economic and political changes when compared to the stagnation and instability of the previous fifty years. Examining this kind of historical development more carefully allows us to understand and better help countries in their quest to establish the capacity to effectively rule, as well as to foster economic development.

Solving the chicken and egg problem

Using Mexico as an example, let’s look at some of the reasons why it is difficult to solve the chicken and egg problem.

First, the size of the territory matters for building state capacity. Throughout much of human history, city-states have been one of the most common types of state organization. Leaders of small regions can more easily solve the chicken and the egg problem. In cases where the population is small, the ruling elite will personally know more of the people serving under it, and find it easier to use rewards and punishment to control their behavior. Small regions are likely to be more homogenous, which empirically decreases the cost of providing public goods, perhaps because there is less conflict over what is to be provided, and to whom.

When dealing with a large country, however, a leader will need more impersonal mechanisms of control, and these are much harder things to create. Mexico at the time of independence was a very large country, including modern-day Mexico and Central America as well as much of the now-US Southwest.

To govern such a large country, the central government needed a strong army to make sure that the state governments paid their tax assessments. But it was exactly this reason that the state governments had little incentive to fund such a strong military.

The country was so large, and the roads so poor, that the central government did not even have a clear sense of the country’s borders, let alone full control of it. It became better mapped in the mid-nineteenth century and it was only then that the likes of General Antonio López de Santa Anna realized exactly how much territory the country had lost to the United States.

Geographically, only a third of Mexico has relatively level terrain and there are very few navigable rivers, making transportation costly. The colonial authorities had done little to build up an efficient transportation system, and in 1800 there was only one road in the country that could accommodate wheeled transportation and even there, most transportation was still done with mules.

Transportation difficulties created a system of regional, isolated markets, which reinforced political decentralization and decreased the capacity of the federal government. The militias and police departments that did emerge tended to be very poorly funded and served mostly to protect whoever created them and not to protect any kind of impartial justice.

Unfortunately, transportation issues did not change much until railroad construction took off in the latter part of the 19th century. By the 1870s, the road network suitable for wheeled transportation was less than five kilometers per 10,000 people in Mexico, around a tenth of what was available in the US.

The failure to develop an efficient transportation system was caused in large part by the chicken and egg problem – the central government was unable to raise much revenue, which made it difficult to build roads and infrastructure, which meant it was difficult to have much state presence outside central Mexico.

Second, experience matters. Regions that have experience with centralized state authority tend to be able to re-establish it more easily and quickly than regions without that history. Mexico had little experience with effective government and tried to impose a state on the populace from the top down.

There has long been a mythology in economic history that Spain was a strong, centralized state and ruled its colonies accordingly. In actuality, Spain had only two viceroys in the Americas, one for North America and one for South America. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was incredibly large, including modern Mexico and the territories mentioned above in the present-day United States and Central America, plus Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, and even the Philippines, on the other side of the world.

Centralized administration of such a large territory necessitates a specialized and professional bureaucracy that can provide the leader with good policy advice as well as an administrative oversight of the different regions.

The viceroys, however, had few staff, let alone a centralized bureaucracy, and the staff that they did have were just their personal attendants, not administrative agents. Until the late eighteenth century, there was no system of provincial officials below the viceroy. Even when those positions were created, there was no formal system of government or laws. These authorities didn’t have any significant military force, nor did they have any official ability to collect taxes. When the Spanish king was overthrown in 1808, any vestiges of this nascent state capacity seemed to be destroyed in the chaos and violence of the wars for independence.

Third, developing state capacity requires money, something that the Mexican government was short of throughout much of the nineteenth century. It was short of money for a huge range of reasons, all of which boil down to unlucky shocks.

One issue was the war of independence. This war, which lasted from 1810–1821, was devastating to the Mexican economy and the state’s ability to collect taxes. There was an enormous amount of capital flight, which began even before the war.

The war also hurt mining. Many mines were flooded and destroyed during it. Silver output, previously the mainstay of the Mexican economy, fell to its lowest level in the 1820s, under half of what it was in the 1810s, and it was not until the 1860s and 1870s that the industry really began to recover. Silver mining had many links to other parts of the Mexican economy, which meant that the collapse of mining in the post-independence period also led to a reduction in production of other goods.

The fall in mining also had a direct fiscal effect: revenues from mining taxes fell. What’s more, at the time Mexico was only able to finance imported goods with its exports of silver. Most government revenue came from tariffs. Without silver from the mines, little could be imported. Combining both effects, the reduction in international trade due to mining problems meant a severe contraction of government revenue.

Tariffs tended to be high (sometimes 100–150 percent the price of the product), outdated in terms of their valuation, and extremely inconsistent. The political instability of this time, combined with the fact that the central government had little real monopoly on violence, meant that there was uncertainty over what tariffs actually were. Between 1821 and 1867, there were eight separate general tariff schedules. If a merchant imported a good not on the schedule, then the tariff was at the custom inspector’s discretion. There were internal tariffs between states, a practice that the central government sought (and failed) to eradicate on numerous occasions – reminiscent of the Holy Roman Empire in the late 1600s, where there was a river toll along the Rhine every six miles.

While the external tariff schedule was supposedly set by the central government, it was enforced in a haphazard manner depending on which port was being used. Even as late as 1941, the state of Yucatan was still able to charge different rates.

Loading so heavily on one major source of funds also caused another problem. When local leaders rebelled, they would often raid the nearest customs house and then reduce the tariff rate at that port to get more business. General Arista in 1845, for example, rebelled against the national government and offered merchants a 40–45 percent reduction in tariffs for using the ports of Tampico and Matamoros.

The aftermath of the independence war brought its own challenges: trade dislocation and disorder. Old colonial trading networks had been disrupted and merchants had to find new contacts and avenues for trade. For instance, the break with Spain meant that Mexico had to look for a new supplier of mercury, an essential ingredient in the production of silver. Between 1800 to 1850, Spain produced almost 80 percent of the world’s mercury (in Iberia) and had cut diplomatic ties. Mexico tried to create its own mercury mines, but lost them when it ceded the West Coast and Southwest to the USA. Ultimately it ended up using British merchants to buy mercury indirectly from Spain – at a substantial markup.

There were other unfortunate legacies of the independence war. Félix María Calleja, viceroy of New Spain from 1813 to 1816, had no money to pay officers. He instead allowed them to ‘self-finance’ through looting Mexican civilians in the land they marched through. He urged elites to create and fund their own independent non-state militias. Such alternative statelike forces – a deliberately encouraged challenge to the supposed state’s monopoly on violence – pushed against building more state capacity.

There were so many revolts in the post-independence era because the state was unable to enforce its monopoly on violence. Given this economic and political turmoil, it is not surprising that the central government had so much difficulty raising taxes after independence as well. The government turned to foreign countries, which had been shut out of Spanish colonies, to borrow money but the economic growth that would allow them to repay these loans did not occur and they defaulted on their loans to British private lenders in 1827. Lenders would not make the same mistake again.

Lastly, after the war of independence, regional strongmen had sought to preserve the powers they had received during the war, and that often included the right to tax their regions. The more disorder there was in the provinces, the more difficult it was for the central government to impose its authority. It was a vicious cycle, in that banditry was both the result of a weak central state, as well as making it difficult for the government to develop strong state capacity.

First steps towards state capacity

After the expulsion of the French, the government of Benito Juárez knew that Mexico needed a centralized police force that could provide order after many decades of chaos. His attempts to deliver such a force were the first real steps taken to create state capacity in what had otherwise been a very unstable, almost anarchic, fifty years since independence.

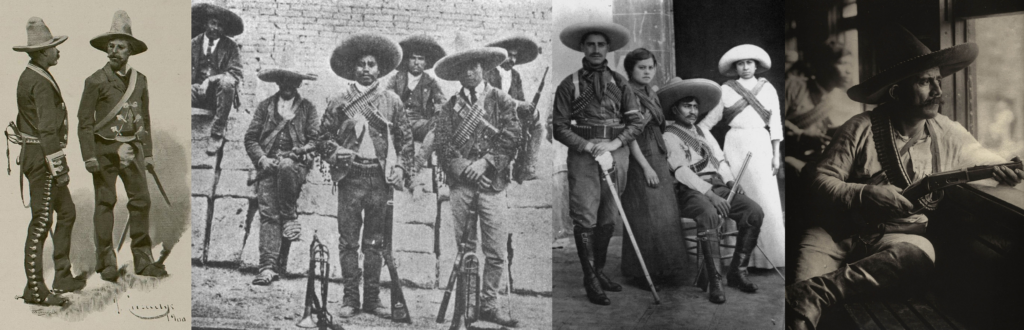

The creation of the Mexican Rural Police force (‘Guardia Rural’, known as Rurales) was in no way a panacea for the central government’s problems. For starters, they had to fill the ranks of the police force and many of the new recruits ended up being drawn from the ranks of bandits – or even pursued banditry alongside their new responsibilities. This overlap between banditry and police force would remain a long-standing issue as the newly minted police officers often relied on banditry on the side to make more money. Highlighting this overlap is the fact that the government designed the new Rural Police uniforms to look like some of the most well-known bandits of the century, the Plateados:

His uniform distinguished the Rural. It confirmed his transition from bandit to lawman, since the Rurales dressed much like the most powerful bandits of the time, the Plateados. Both wore the charro outfit, and everyone understood what it meant: its wearer could outride, outrope, outshoot, outdrink, and outwomanize any other cowboy, from whatever land. The Rurales rode and strutted in dove-gray bolero jackets and suede-leather, tight-fitting trousers embroidered with ornate braiding and studded with silver buttons. On their heads they wore the heavy felt sombrero that had emerged as a national symbol.

Twenty years after its creation, Porfirio Díaz had increased the membership of the rural police force by 90 percent and they had become a symbol of both the order and ruthlessness of the Porfirian state.

Of course, the creation of a Rural Police Force and other institutions of a capable state is only possible if the government has money to pay the salaries. And once again, the government faced the old chicken and egg problem.

The Mexican government wasn’t in a position to print money and inflate the currency either. The government had so little credibility with the public that it would have been impossible to issue fiat notes and have people accept them as legal tender, let alone compel their acceptance. It had already reneged on backing previous note issues with gold multiple times and Mexican bonds were trading at a fraction of their face value, making it nearly impossible for the government to borrow more.

So the government cut a deal. Like many governments in history, it contracted with an institution that would be able to perform many of the tasks we associate with government. Díaz organized the government’s creditors into a single bank called the Banco Nacional de México (or Banamex, for short). Banamex would loan money to the Mexican government in return for a number of lucrative privileges, including running the national mint, protection from other competitors, and even the right to collect certain customs and excise taxes.

This strategy didn’t rely on the government being able to protect widespread property rights. Rather, it only required the Díaz government to protect the property rights of one already-powerful group over competing interests. Compare this to Great Britain in the 1500s, when Queen Elizabeth I assigned customs collection to so-called ‘tax farmers’, which were then typically prominent merchants or politicians. These tax farmers often loaned money to Elizabeth, to be paid back with money collected in customs revenue. As noted above, the development of state capacity is messy and protracted, involving making deals initially with local power brokers at the expense of an overall rule of law.

Díaz was the first leader in independent Mexico to put a stop to the constant revolts. He was much more ruthless than previous governments. When the Fifth Corps of the Rural Police rebelled, Díaz had them fired from the force and executed the traitors.

Before this period, it was often profitable to revolt, and ambitious men needed militias to confront rivals and get ahead politically. Díaz used cronyism to make sure that potential opposition became friendly by giving them privileges and protection.

Companies that received special privileges from the government routinely put local and national politicians on their boards of directors, thereby transferring rents to them via director’s fees and stock distributions.

He paid special attention to powerful state governors, who were most likely to be a political threat. When he embarked on tax reform in 1883, he took it to a conference of state governors rather than Congress, even though this was inconsistent with the Mexican constitution. And when the governors disagreed with the tax reform, he decided to not move forward with the plan. State officials were also well represented on the board of directors of major banks and corporations, allowing them to earn additional money.

There are myriad other reasons that Díaz was able to succeed where others did not, including the fact that the US economy was growing rapidly at this point. American investors were searching for new sources of raw materials to supply manufacturing as well as new markets to export their goods to. It’s also important to note that this was just the beginning of the development of state capacity, and some of what Díaz did came with a heavy price down the road; namely, the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1920 that deposed Díaz and transformed the country. Though the Revolution was protracted and bloody, post-Revolution Mexico built off the progress made in the Porfiriato period and did not revert back to the extremely low state capacity of the earlier nineteenth century.

Building a state

Díaz’s strategic agreements with banks, bandits, and state governors served as effective intermediate steps in the pursuit of a stable state. In contrast, contemporary international institutions and NGOs often focus on funding programs and policies that emulate those of already-affluent nations. But the path to achieving state capacity can be a difficult and imperfect one; no country has effortlessly bypassed it.

Learning from Mexico and similar cases suggests that it is essential to build state capacity pragmatically by engaging with veto-players and elites, collaborating with potential threats to state power (such as bandits), and striking win-win deals to appease those with de facto veto rights. Pursuing ideologically or ethically ‘pure’ policy reforms may be less effective.

Development agencies might not all be well-equipped to support this process, but they should still consider state capacity as a constraint in their planning. It is important to acknowledge that many developing nations struggle with basic logistical tasks. One group of researchers, for instance, tested countries’ ability to manage the logistics of international mail. They sent letters to non-existent addresses in the 159 countries that signed the Universal Postal Union Convention, which requires countries to return undeliverable mail to senders within 30 days. They found that only about 60 percent of the letters were returned, with an average delay of over six months.

There is a risk of establishing unattainable targets or implementing policies that create superficial development (like the phony Potemkin villages used by Russian officials to impress Empress Catherine on her visit to Crimea) or divert efforts and resources away from where they would be more useful. Take the example of public education, which often serves as an indicator of a nation’s capacity to provide essential services to its citizens. The Millennium Development Goals advocated for universal education to empower developing countries. However, in the pursuit of meeting these goals, many of these countries focused primarily on boosting enrollment rates rather than genuinely improving the quality of education and fostering an environment conducive to learning. In 2019, the World Bank discovered that nearly 80 percent of children in the poorest nations did not achieve basic literacy by the conclusion of their primary education. This issue was also prevalent in low- and middle-income countries, where over 50 percent of children failed to reach this critical milestone.

Another example is India, where intricate regulations contribute to corruption and resource misallocation. The Indian government faces difficulties in providing essential services, yet it has hundreds of complex, comprehensive, and generous labor laws that largely remain unenforced. Indeed, the vast majority of the labor force is actually in the informal sector.

Overlooking the challenges involved in building state capacity benefits no one. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Douglass North argued in 2011 that the World Bank’s extensive efforts to transform developing countries into successful market economies have largely failed. Policies effective in developed nations can destabilize fragile states by threatening the security of their elites. The case of Afghanistan illustrates that attempts to rapidly build a centralized and stable state can backfire badly. North emphasized that development takes time and setting overly ambitious goals may result in disaster. As former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown put it, ‘in establishing the rule of law, the first five centuries are always the hardest.’