Pour-over coffee has long been popular with coffee enthusiasts, but it frustrated coffee shops because it takes so long to make. That’s changing.

In the US, almost every coffee shop serves drip coffee. It’s made from a machine similar to the ones many Americans have at home. You put a filter paper full of coffee grounds in, the machine dispenses hot water over it, and a pot is filled with coffee.

There are many ways of brewing coffee, though. One is especially elegant, technical, and ritualistic: the hand-brewed pour-over. In the last 20 years, pour-over has become a symbol of quality and craft in coffee.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Pour-over is a challenge for coffee shops. Many are proud to offer it, but the time-consuming process interrupts service and often produces inconsistent results. How to brew the perfect cup of coffee remains a vexing question. Like espresso, new technologies might be poised to revolutionize coffee brewing at home and in the café.

When you think of pour-over coffee, you might think of the V60, the iconic dripper from the Japanese company Hario. Today it’s probably the most popular dripper. But the V60 is a recent development, launching in 2005. The motivations behind the brewer begin much earlier.

Coffee – and what Americans like me mean by that is black coffee, filter coffee, drip coffee – is much more popular in the US than Europe. It became popular after the Boston Tea Party as a more patriotic alternative to the unjustly taxed tea. While the modern espresso machine debuted at the 1906 World’s Fair in Milan, a machine didn’t come to the New World until 1927, when Caffe Reggio in Greenwich Village acquired one. The machines weren’t readily taken up outside Italian American communities until after the war, first by beatniks and artists in espresso cafés in San Francisco and New York. Espresso didn’t explode until Peet’s Coffee – and the more popular shop it inspired, Starbucks – spread across the country beginning in the 1970s. Still, it remains less popular with Americans than a standard cup of coffee.

Pour-over, coffee brewed by hand with a gooseneck kettle and dripper instead of a machine, has similar origins to modern espresso: starting in the 1970s, coffee began to slowly escape its status as a commodity product, where all beans were treated as one. Peet’s began to emphasize their coffee’s country of origin. Brazil has long been a monster coffee producer – today it still accounts for around 30 percent of global coffee production. But consumers began to branch out to coffee from places like Sumatra, Indonesia, or Sidama, Ethiopia.

As modern, specialty coffee really got going in the early 2000s, shops like Intelligentsia in Chicago and Stumptown in Portland placed an even greater focus on the origin of the coffees they served, roasting lighter and naming specific farms or cooperatives alongside the country of origin. Lighter roasts emphasize brighter flavors – the lists of fruit or flowerlike notes that can now be found even in grocery stores – but these coffees also have a tart acidity and run the risk of the grassy, not-quite-coffee taste that comes from too light, ‘underdeveloped’ roasts. Avoiding these flavors and roasting lightly well is difficult and involves a number of advanced techniques, like a ‘declining rate of temperature rise’ throughout the roasting process (a negative second derivative – coffee gets surprisingly technical). In the late 2000s, software like Cropster let roasters track their data and iterate, making it much easier.

A new world of coffee was created: specialty coffee consumers did not simply want super-dark French roast coffees that always tasted like caramelization, chocolate, and smoke, no matter the origin. They wanted a buffet of coffee offerings from around the world.

This put coffee shops in an awkward position. Few coffee shops had the volume to offer more than two or three coffees as batch brews, made in industrial-sized coffee machines. Brew too much coffee and it would become stale or tepid before it was finished. In practice, this often amounted to three vats of coffee behind the bar: a dark roast, a light – though not usually very light – roast, and a decaf.

Coffee shops wanted to sell many different types of beans for customers to take home. As desire for single-origin coffees spread, shops would sell 10 or even 20 different coffees. With only two or three brewed coffees for sale, café goers wouldn’t be able to sample most of the offerings. And – despite the European allure of the espresso shot – a well-brewed cup of coffee is often the best way to appreciate complex, fruit-driven coffees that the coffee world was increasingly excited about. Espresso is so concentrated that it is hard to decipher the different notes and flavors. It’s a bit like why people sometimes add water to whiskey. This is why the very best coffee shops in England and Europe serve drip coffee, despite most of the Continent preferring espresso.

In response, some shops began offering pour-over. This was the founding promise of Blue Bottle Coffee, the famous San Francisco shop, when they started in 2002: ‘to brew coffee to order, using the pour-over method’. Even after being purchased by Nestlé and growing to over 100 shops, Blue Bottle’s black coffee is still hand brewed.

Many shops are less willing to do this and the reason is simple: time. A pour-over in ideal conditions takes about three minutes to brew, not to mention another minute or two for prep and clean up. A skilled barista could make ten espresso drinks in that time. A nice café near my office has a warning on the menu: ‘manual brew, wait time 10 minutes’. That shouldn’t be too surprising – recall that espresso was invented as a time-saving measure. Nevertheless, consumers would almost never be willing to pay commensurate with this time cost – variety wasn’t worth ten-dollar cups of coffee.

There are two basic ways of brewing coffee: percolation and immersion. The widely known pour-over devices – the Hario V60, the Chemex, and the Kalita Wave – all use percolation to brew. Water percolates through a bed of coffee and drips into a cup or carafe. This tends to give coffee a clean taste, free of coffee grounds, but it is highly sensitive to minor changes in grind size, agitation (from the pouring speed, or shaking or stirring the coffee grounds). This is because – to simplify a bit – there is an optimal contact time between the water and coffee, and those factors dictate that time.

For percolation to be optimal, a few things have to go right: water shouldn’t be able to bypass the bed of coffee, as that will lead to a watered-down brew. But the dripper cannot be clogged either, as that will lead to too strong a coffee. The water must flow evenly through the bed of coffee, without creating veins of fast-flowing water, a defect known as channeling. The grind, besides controlling the speed of water flow, also dictates the exposed surface area of coffee (a finer grind leads to more surface area), so it must be balanced with the total amount of water used to brew.

You are probably also familiar with immersion brewing. The most famous immersion device is the French press. Coffee sits immersed in water and a metal filter prevents (some) of the grounds from being poured when it is served. You might have also tried Turkish coffee or cold brew. They too use immersion. Immersion is a much more forgiving method in terms of grind size and brewing time, as the grounds simply sit in water, rather than passing through it. Think of your second cup from a French press; it is still very good, despite having brewed for ‘too long’.

Some devices use both, like the underrated Hario Switch or the popular Aeropress. The Switch looks like a V60 but a small metal piece plugs the bottom. The coffee is immersed in the water for a few minutes, after which the metal piece is moved and the coffee water is drained out. This captures some of the best of both worlds: the simplicity and forgivingness of immersion with some of the clean taste of paper-filtered percolation. The Aeropress works similarly, first immersing then percolating, though it allows you to push the coffee through the filter, rather than having to wait for gravity.

Cafés have brewed coffee many different ways over the centuries. Early coffee brewing was done through immersion, what would today be called cowboy coffee. Coffee grounds are added directly to boiling water and brewed, never filtered out. You might still try this, like I did, in the desert of Wadi Rum, or more likely on a camping trip with some adventurous friends. This technique is similar to modern-day Turkish coffee, though that uses a special, extremely fine grind, and spices and sugar are often added.

The primary goal of early changes in brewing seems to have been to remove coffee grounds in order to get a more refined final product. In seventeenth-century France, coffee was brewed like tea, using linen bags to hold the coffee. The French also used special coffee pots, where the angle of the pouring spout caught most of the grounds.

Coffee historians suspect that, at some point, somebody brewed coffee through a sock. So began percolation brewing, and with it the trend toward filters. These were first made of cloth, then much later of paper. Percolation also flourished in the form of siphon pots, like the modern-day Italian moka pots. In these, water percolates up through a bed of coffee and spills out into a holding chamber. Because the coffee is moving upward, gravity keeps most of the grounds out of the finished coffee.

Once paper filters were cheap and widely available, the modern pour-over dripper began to take shape. A famous example is the Chemex Coffeemaker, which was released in 1941. The device combines the dripper on top and carafe on bottom in an hourglass shape. It’s now a quintessential example of mid-century modern design.

The Chemex is designed for brewing multiple cups of coffee, usually two or three. While beautiful, its large filter papers can be slightly unruly – sometimes they get stuck to the spout, which prevents air from escaping and halts the percolation.

In 1954, the electric drip filter machine – or in standard American parlance, the coffee machine – was invented. The first was the Wigomat, invented in Germany by Gottlob Widmann. In 1972, the Mr. Coffee was created in the USA and it quickly spread across the world – both inside homes and stores.

As much as some coffee connoisseurs hate to admit it, a well-made but relatively inexpensive machine like the 1971 Moccamaster can often brew coffee better than you can with a pour-over.

There are two main reasons as to why electric coffee machines can work so well. The first is heat retention. A coffee slurry – the mixture of coffee and hot water – must be kept hot as the coffee brews. The energy from hot water extracts compounds from the coffee. Light-roast coffees especially are less soluble than their darker counterparts, and benefit from higher brewing temperatures. Yet the slurry loses heat as it percolates, both to the cold air around it and to the thermal mass of the brewer itself. Some of the most beautiful dripper materials – copper, glass, ceramic – have lots of thermal mass, so they pull more heat from the slurry and indeed radiate more heat into the air. Plastic, unfortunately, is best on this account. If you are buying a V60, you are probably better off with the $10 plastic version over the stunning $68 copper one. (Full disclosure: I still use a glass version, with an intense preheating cycle.) In a machine, this simply isn’t as much of an issue, as the internals of the machine heat up with the water.

The second advantage of machines is that they do the same pouring motion every time. Small adjustments, like the height and angle of a kettle, can make surprisingly big differences in the flow rate of the water. Faster pours agitate the coffee grounds. Consistent brewing requires consistent pouring. On average, the machine does better.

Neither coffee shops nor coffee enthusiasts always weigh the pros and cons of machines and hand brewing rationally. Some people – including myself – simply love the ceremony of the pour-over. Some, like Blue Bottle, seem to believe the ritual is of inherent value, no matter what a machine can do.

The 2005 V60 seemed to offer a compromise: it brewed better than earlier brewers, which used ‘coffee filter #2’ papers with a flat, trapezoidal bottom that water got stuck in. The 60 in V60 refers to the degrees, a rounded cone that directs the water toward a hole at the tip of the cone. The angle allowed triangle paper filters to fold into a cone. It offered Japanese elegance and precision – and a great cup of coffee.

The brewer became an instant hit with consumers. Yet coffee shops, struggling to keep up with pour-over orders at 8am on a Monday, were forced to confront the problem of whether to take up the ritual. Even if a shop could afford the costly time it takes to prepare pour-overs, the results were still inconsistent. Extensive barista training was needed. Hasty brews left customers disappointed.

We almost solved this. Well, Starbucks did.

Coffee poseurs hate Starbucks because they resent the delicious frappuccinos. Genuine coffee lovers hate Starbucks because they killed the Clover.

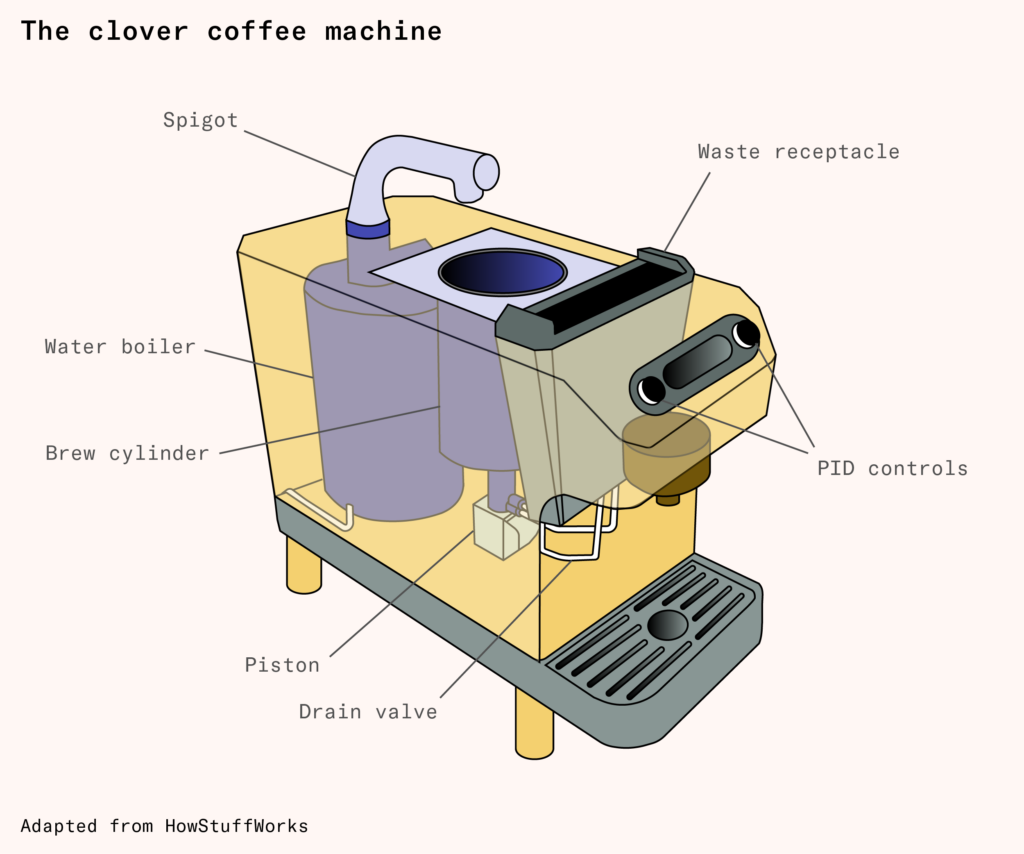

The Clover was a machine built by the Coffee Equipment Company. It launched in 2006. The machine was built for cafés to brew single cups of coffee. It worked like this: coffee grounds were dumped into a brewing chamber on the top of the machine. A spout filled the chamber with water at a preprogrammed temperature. The barista briefly stirred the grounds. The coffee brewed for about a minute, and the bottom of the chamber – a mesh filter – began to rise, sucking the coffee through the machine and pouring it into the cup while catching all the grounds on the top of the machine. Those grounds can easily be swiped into a built-in dump.

One hundred units of the machine were sold in their first year, 2006. Sales grew rapidly in 2007.

Rumor has it that Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz had his first Clover coffee at Café Grumpy in Manhattan and said it was the best coffee he had ever had. On 13 March, 2008, the company was acquired by Starbucks. Sales were cut off to outside cafés. CloverNet, a support forum, was shut down 60 days after the acquisition.

Eric Perkunder of Slayer Espresso called it ‘Starbucks’s secret weapon’: it would both shore up their defenses against McDonald’s McCafé at the low-end market by allowing them to offer truly ‘fresh’ coffee, as opposed to McDonald’s vats, which sat all day at dangerously high temperatures, 80–90 degrees Celsius even after the infamous lawsuit. At the same time, it allowed Starbucks to compete against the high-end specialty market by making truly delicious coffee.

In 2013, over 500 stores had Clovers and Starbucks was planning to continue the rollout. But six years later, in 2019, Starbucks was retiring its Clover machines.

What happened? Reading between the lines, it seems that Starbucks was never able to effectively court specialty coffee drinkers, just as Nestlé wasn’t able to even after its acquisition of Blue Bottle.

The acquisition was likely part of Starbucks’s larger strategy to compete with the fan-favored large Third Wave chains, like Stumptown, Blue Bottle, and, more recently, Verve. The cornerstone of this strategy was Starbucks’s Reserve Roasteries and Bars, which roasted and sold coffees far better than Starbucks’s standard offerings. At the same time that Clover machines began to be phased out in 2019, plans to open 1,000 Reserve stores were scaled back, and only a few have opened since then. There are now six Reserve Roasteries: in Seattle, Shanghai, Milan, New York City, Tokyo, and Chicago, along with 43 Reserve Bars. Today, they are the only places you are likely to see a Clover.

The original champion of the Clover and this broader strategy – Howard Schultz – also retired in 2017.

There was also broad consumer interest in other drinks. Nitro cold brew exploded onto the coffee scene in the 2010s. Where for traditional cold brew, coffee sits immersed in refrigerated water for around 20 hours (and gets a bit stale in the process), in nitro cold brew N2 is used to push out the air to prevent oxygenation and gives the coffee the foamy texture of a stout ale. Nitro is stored in a keg with a tap, which takes up valuable real estate on Starbucks’s counters. Nitro, along with other viral drinks like the Unicorn Frappuccino, the Iced White Chocolate Mocha, and the Pink Drink, not the fresh coffee produced by Clover machines, was what allowed Starbucks to hold their edge against the low-end market.

Starbucks recently announced a follow-up to the Clover, the Clover Vertica. The machine simplifies the Clover brewing process by adding bean storage and a grinder into the machine. This essentially makes it an automatic coffee machine: press one button, and wait for the coffee to come out. Above all, Starbucks argues that the new machine is even faster than the original, implying speed persisted as an issue even at one minute per cup.

Starbucks says they plan to roll the machine out to thousands of stores. Will it be as good as the original Clover? Automatic machines haven’t worked well before, so I wouldn’t bet on it, but I am excited to try it.

I don’t hold any ill will toward Starbucks – and indeed admire their desire to up their coffee game. But no machine has quite been able to play a similar role since.

There have been a few attempts since the Clover to find a solution to the problem of how to offer and sell different filter coffees.

Some coffee shops have kept it simple. At the highly regarded Cat and Cloud in Santa Cruz, California, they do not offer pour-over. Instead, they take the old-school approach of brewing three vats of drip coffee with a machine. These are kept in sealed, highly insulated carafes, so the coffee stays hot and fresh. One of those is an upgraded version of the traditional dark roast coffee. It’s called Night Shift. If you like dark, strong coffee, but wish for something better than the standard, I would highly recommend it. They also brew a decaf version. For their light roast, they offer whatever new or exciting coffee they are selling in store. Sometimes this is even a very expensive coffee – at one point it was a rare Geisha, among the most expensive coffees in the world – but they keep the price steady at $3.75, sacrificing profit to get consumers interested in higher-grade coffee.

In some shops, the pour-over coffee will simply be the most expensive thing on the menu. In New York, the stunning Danish La Cabra shops serve hand-brewed coffee from eight dollars to ten dollars. All are very special coffees available only at La Cabra. The line in New York often reaches out the door and sometimes down the block.

But many shops are experimenting with new forms of pour-over automation.

One machine to do this is the Poursteady. I tried coffee made from it in a café in Monterey, California, called Captain + Stoker after a very cold morning of scuba diving. The Poursteady is automated, but it works just like a manual pour-over. A small hose plays the role of the barista, spraying water into a brewer according to customizable instructions, blooming the coffee to release excess CO2, then doing multiple pours, stopping and starting. The Poursteady can use any manual pour-over brewer. In the image below, there is a Kalita Wave, a Fellow Stagg, and three V60s. When I visited, Captain + Stoker was brewing five V60s simultaneously. The coffee was very good.

The Poursteady misses some of the benefits of coffee-brewing machines – better thermal control and the efficiencies of brewing several quarts of coffee at once, for example – but customers get to watch a version of the pour-over ritual they love.

I’m not sure why the Poursteady hasn’t had a wider adoption yet. Price might be a factor: their five-spout machine is about $14,000 and needs accessories like scales and brewers. That’s comparable, though, to a café-quality espresso machine, which could easily cost $20,000–$30,000. The Clover was about $11,000 in 2006 – around $17,000 today – and it could only brew one cup at a time.

Speed is likely a larger factor. Each brew on the Poursteady takes as long as it would by hand. The Clover’s unique immersion and vacuum system allowed it to brew in a minute. The Clover also had a convenient cleaning system, where the Poursteady still requires preheating brewers, washing the filter paper, and cleaning out the grounds after brewing.

I tried another, similar machine recently at Little Wolf Coffee, a renowned shop tucked in the northeastern corner of Massachusetts. It’s called the Tone Touch. Like the Poursteady, the machine sprays water into a brewer from above. The Tone Touch I tried was using a Tricolate – a new and trendy dripper. The Tricolate and other vertical brewers like it are called no-bypass – a term coined by astrophysicist-cum-coffee-expert Jonathan Gagne. These brewers are designed to prevent the water from escaping along the sides of the filter, extracting too much from the edges of the coffee bed and not enough from the center. Since more water goes through the coffee, more flavor is extracted, so you end up with a tastier cup.

Unfortunately, while these no-bypass brewers tend to make better coffee, they have long brewing cycles, six to ten minutes, rather than the three minutes you might expect with the V60, let alone the Clover’s one minute. I suspect this is why the oldest vertical brewer I know of, the Aeropress, allows the user to push the coffee through the bed. Most of the best Aeropress recipes can be made in two minutes or less. So once again, an automated pour-over has solved part of the problem but not all of it.

There are a few other automated pour-over machines on the market. The Verve coffee shops use built-in ones from Modbar. There’s also the Marco SP9.

Another approach can be found in the xBloom, which debuted last year. The first machine was geared toward homes, but in late spring they came out with a new machine more oriented toward cafés, especially ones pursuing automation like the (in my opinion underwhelming) Blank Street chain. The xBloom machines begin with a simple premise: people love the convenience of pod machines, despite the high cost of pods and the so-so coffee they produce. Is it possible to make a pod machine that delivers great coffee?

xBloom thinks so. They fill their pods with high-quality coffee beans from top roasters, not ground coffee. The machine includes a grinder that uses a step motor to reliably reproduce 30 different grind settings, each a relatively precise 18.75 micrometers apart. There is an RFID chip in each pod, which the machine scans. The chip tells the machine which of the 30 grind settings to use, what temperature the water should be, and how much it should add, and then a small nozzle dispenses hot water over the coffee, much like the commercial pour-over machines above.

The goal is to solve a problem that has long plagued roasters and coffee drinkers – the same coffee that tastes delicious ground at the right setting on a high-end professional grinder and brewed in a coffee shop might wind up tasting sour and chalky ground on the wrong setting at home. Together, these instructions remove the trickiest part of coffee making: a deep understanding of ‘dialing in,’ or modifying grind settings and brewing to meet the needs of specific coffee beans (using taste as a guide). Reviews so far have been largely good, though the grind consistency issue hasn’t been perfectly solved.

Only time will tell, but xBloom could be a winner: shops could offer all their coffees in pods, and customers would be able to brew exactly the same cup at home as they tried in the café. Baristas would require no additional training. The whole process is automated and requires little cleanup. Of course, they would have to find a way to profit despite the fact that pods are always sold at a high markup.

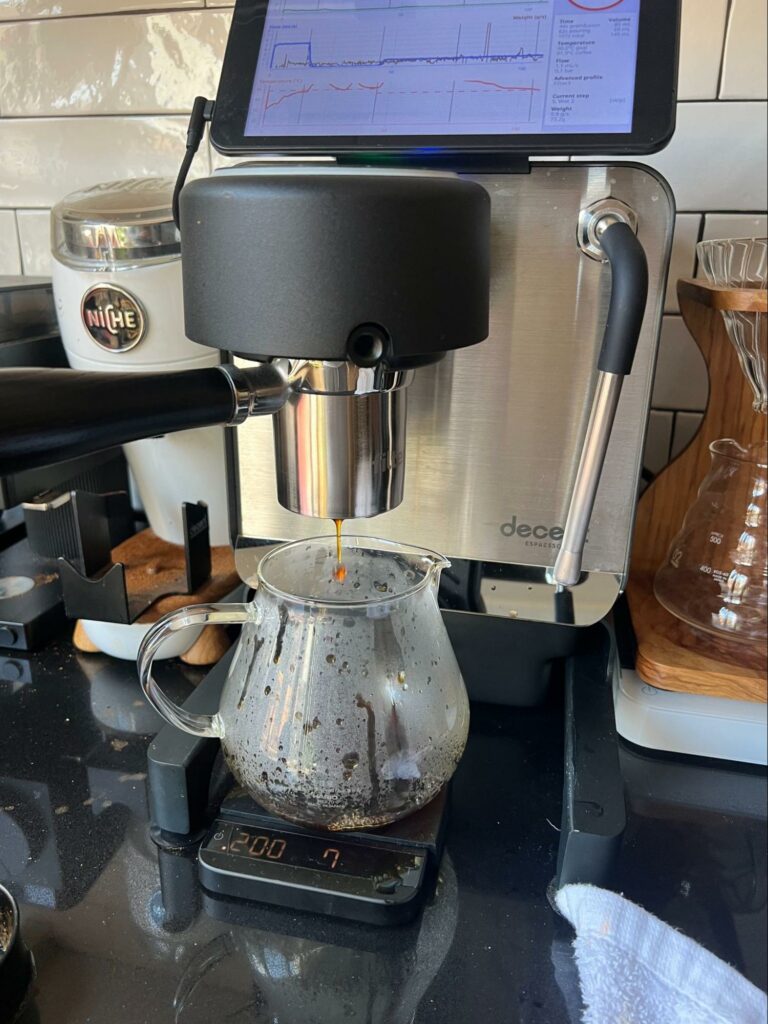

And then there is Decent Espresso. I think the Decent Espresso machine might be the future of espresso. It’s possible that the Decent is also poised to be the future of filter coffee.

I noticed something weird when I visited Suited, a shop near my office in Manhattan’s Financial District (and one of the very best shops in the city). The basket on their Decent protruded through the bottomless portafilter, about four or five inches down. This was not the Filter 2.0 being discussed online, nor even Filter 2.1. This was something new. Apparently, it was Filter3, the newest innovation from coffee legend Scott Rao.

Decent Machines allow you to control the pressure, flow rate, and temperature of the water. Not only does this allow you to create customized espresso shots, but by tinkering with the settings you can use the machine to make super-long, no-pressure shots – in effect, pour-over. People have been playing around with this since the machine came out, but, with Filter3, these efforts seem to have come to fruition.

Rao says that he designed the shot with the café experience in mind: something that was easily repeatable, does not require extensive training, and delivered great coffee. I picked up one of the new baskets on Rao’s website as soon as they went on sale. In my estimation, he achieved his aims.

Rao’s Filter3 recipe combines the automation already built into the Decent with a few extra tricks. The basket is cylindrical, just like all those new no-bypass vertical brewers. All the water that comes out of the Decent flows directly through all the coffee. The basket takes a small paper filter at the bottom, giving the coffee the clean taste one expects from a percolation coffee. The paper also slows the brewing, so a certain amount if immersion happens within the basket. Because the basket is against the grouphead of the espresso machine, it conducts heat from it and stays very warm throughout the brew.

The Filter3 coffee I’ve been making is delicious every time. Where sometimes a pour-over can taste a bit too thin and slightly sour, I’ve consistently brewed deep, rich coffee even from very light-roast beans.

For some reason – probably because there is a certain amount of immersion brewing going on in the basket – the method is not highly sensitive to grind size. A very coarse grind is always recommended. Like with an Aeropress, the paper filter slows the brewing. This combination makes it very forgiving, and yet always delightful.

I decided to conduct a test of my hand made brewing against Filter3. To do this, I got a refractometer, a device that measures total dissolved solids (TDS) in liquids. In general, the higher the TDS, the better the coffee. This isn’t always the case: super-high-TDS coffee is controversial. But usually, for relative amateurs, extracting more will lead to a better cup of coffee. The Specialty Coffee Association recommends extractions between 18 percent and 22 percent.

For my first brew, I used 22 grams of Damian Chavez, Hondouran washed beans from Cat and Cloud. Upon testing, my total extraction was 20.44 percent. I brewed a V60 with the same coffee with an extraction of 16.69 percent. Over more brews, my extraction was consistently higher with Filter3.

Suited uses the very sensible strategy of brewing a few coffees as batch brews, but also offering a daily menu of specialty coffees to sample with Filter3 on their Decent. These coffees are premeasured, so a barista simply grinds them into the large basket and starts the cycle on the machine. In total, it takes about three minutes, just faster than a typical pour-over and with an easier cleanup.

The method is scalable. Decents have relatively small footprints, and, at $4,499 for the top-of-the-line model, buying a few is competitive with other machines like the Poursteady. Plus, they function as full espresso machines, if you need to use them at an event. It’s a killer combination: a state-of-the-art espresso machine and a great ‘drip coffee’ machine in one. I wouldn’t be surprised if it starts picking up steam.