A monstrous plan to build major motorways through some of London’s greatest neighborhoods fell apart. But the price was the birth of the NIMBY movement, and a permanent ceiling on Britain’s infrastructure ambitions.

London is a city of few motorways, and you cannot drive them for long without hitting a ghost. Take the northerly M1, which concludes at Brent Cross with a ski ramp heading into the open sky; or the M11, which starts at junction 4, like an urbanist’s riddle. The M23 from the south manages to drop from a six-lane highway to a village high street in half a mile, hiding a secret 45 meter-wide road in the middle of an unreachable forest. Meanwhile, in the shadow of Westfield shopping center, authorities successfully camouflaged a motorway-sized gap in the urban fabric beneath a campsite for travellers. Unfinished slip roads and missing flyovers seem to beckon at every junction, like doorways to a Neverwhere London.

This feeling of being haunted is no illusion. In 1965, London got a new local government – the Greater London Council (GLC), which united the city and suburbia for the first time. For the next eight years the GLC embarked on what might have been the most ambitious building project in the city’s history, and every one of these loose ends in London’s motorways was meant to connect to a part of it.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

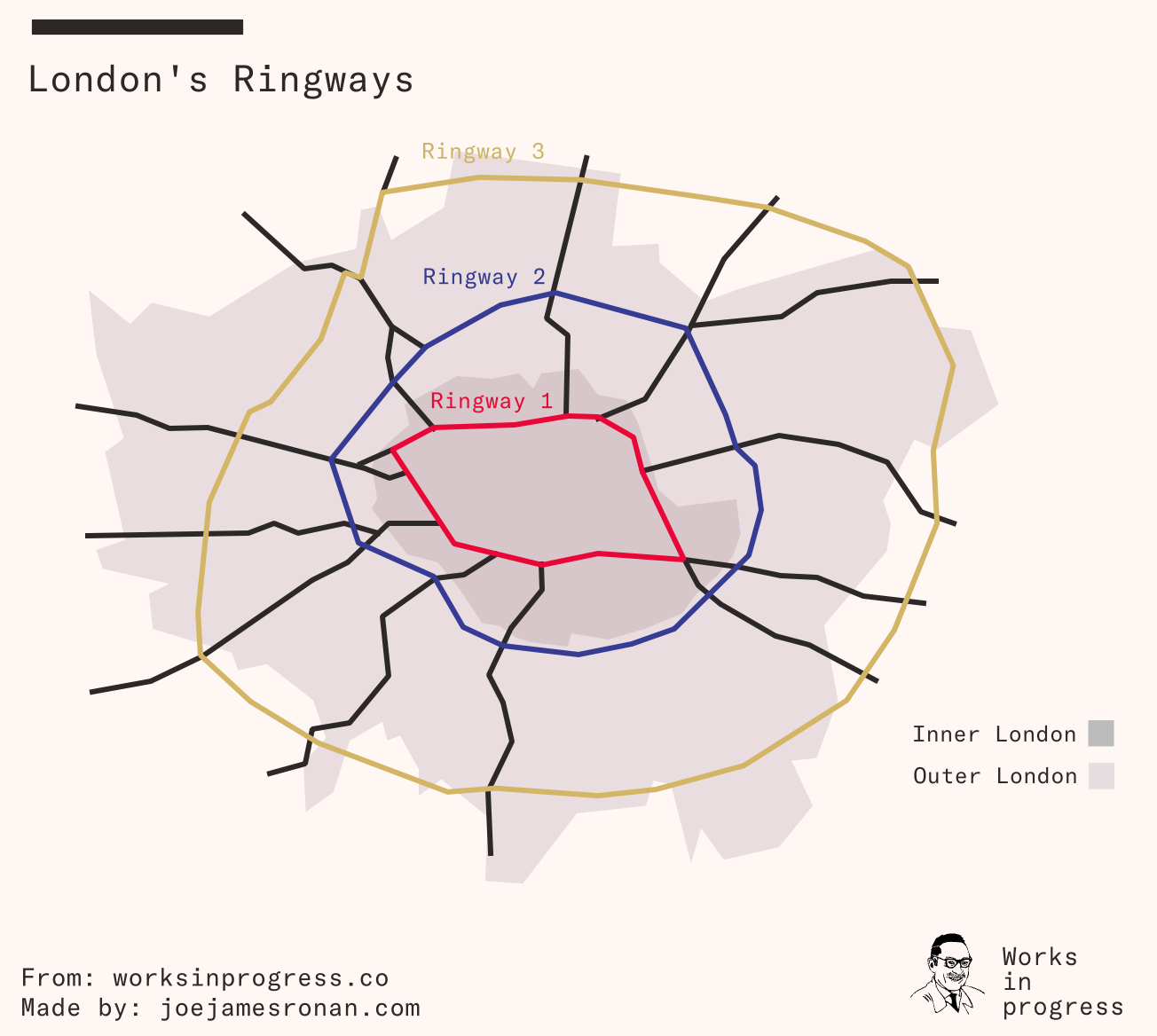

London’s historians often talk about great civic efforts like Bazalgette’s sewer system and the London Underground, but these are dinky compared to the plans for London’s Ringways project—an unbelievable 478 miles of motorway that would have cut apart the city and stitched it back together in a shape unrecognizable to us today.

The failure of the Ringways may have left only a few physical traces, but it left social and institutional impacts that upended what it meant to build in Britain, and which define the planning battles of today. And while almost any modern reader will likely be relieved that it failed, in an era when we must reinvent the city in the face of climate change, we will be relearning the lessons of past grand projets—whether we like it or not.

The nightmare around the corner

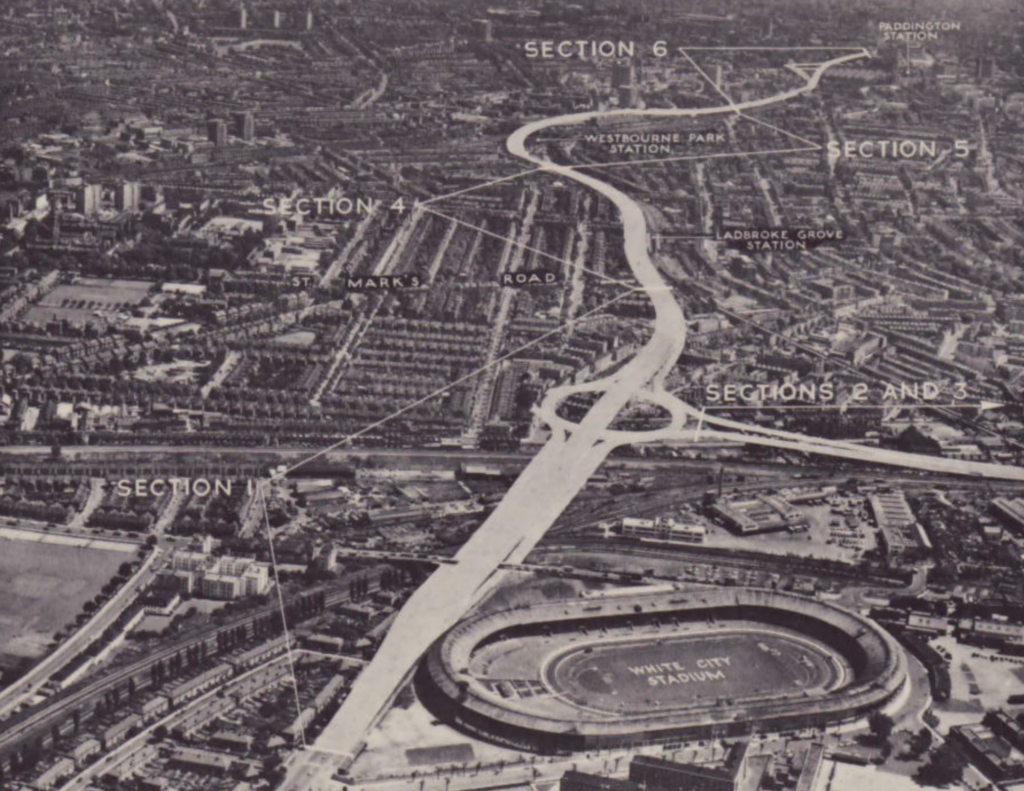

Today, London has only one ring road – the M25 – which runs through the city’s rural fringe, often over 20 miles from London’s official center at Charing Cross. But back in the sixties, the intention was to have three linked together with new and extended radial motorways stretching all the way into what would become Zone 2, which includes Brixton, Holland Park, Maida Vale, Bethnal Green, and Camden. The overall effect would have been to turn the map of London into a gigantic dartboard.

Each section of the project had its own plans for sacrilege. The outermost ring road, Ringway 3, would have been built next to some of London’s leafiest suburbs, not to mention across the remains of Henry VIII’s favorite palace at Nonsuch. In the middle, Ringway 2 would have crashed through the endless terraces of south London before crossing the Thames, putting the finish line of the river’s annual boat race in the shadow of a six-lane concrete bridge. One square mile of prosperous Chiswick would have played host to not one motorway, but three.

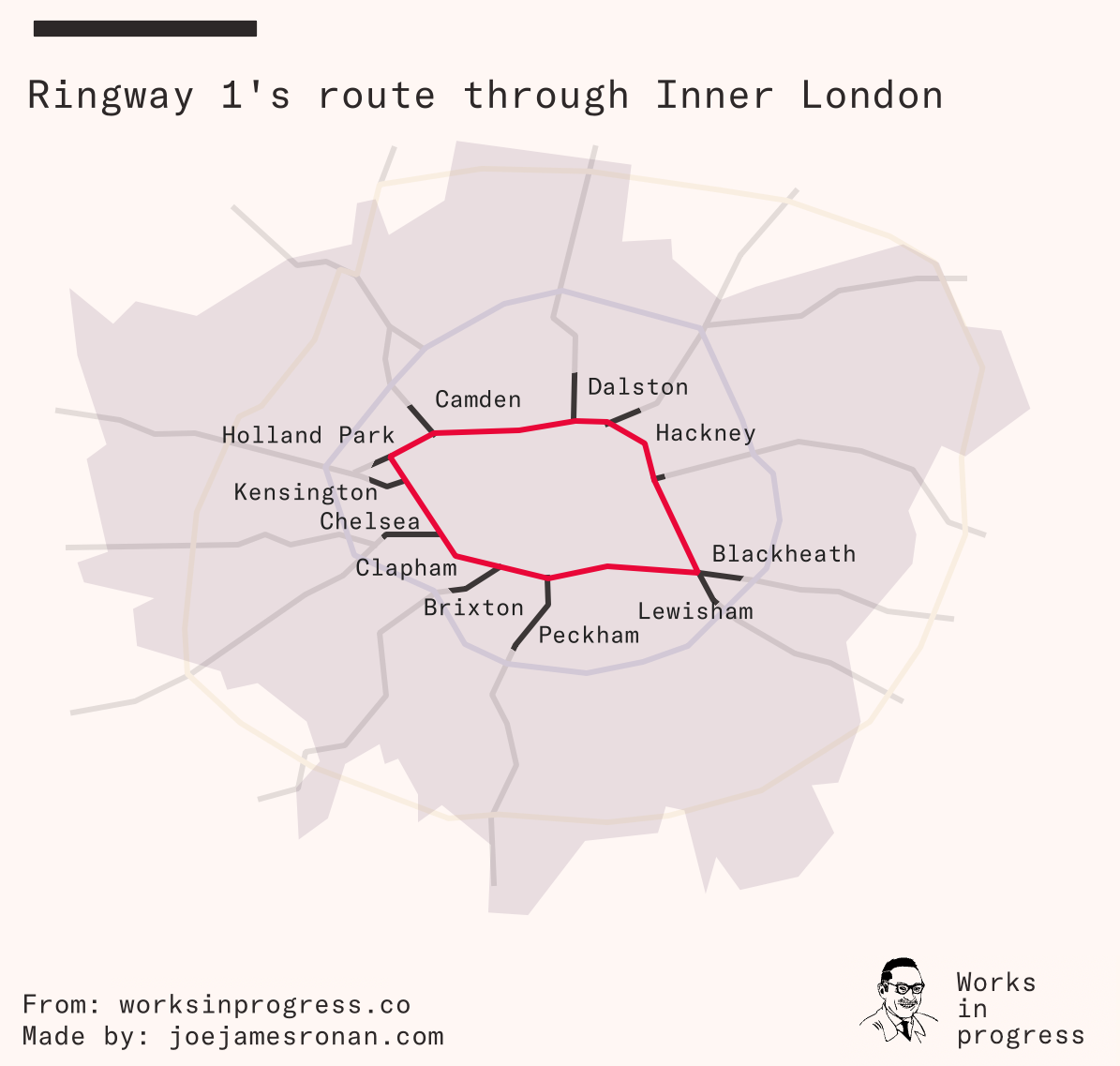

But it is Ringway 1, at the center, which most shocks the modern observer. Originally referred to as ‘The Box’, it was a four-by-six-mile insertion that would have submerged many of modern London’s liveliest areas. If we traced the route clockwise, every hour would be marked by destruction. At one and two o’clock, Dalston and Hackney would have gone from being the site of trendy nights out to enormous interchanges.

The list of destruction was kept going by the historic neighborhood of Blackheath, urban Lewisham, and up-and-coming Peckham, while at six o’clock the middle of Brixton would have been leveled as part of a comprehensive redevelopment plan. Southwyck House, which is known as the Barrier Block because of the fortified exterior it presented to the planned route of the motorway, is another ghost – its zigzag walls were designed to deflect noise back towards the highway.

At eight, Clapham Junction station would have been buried under a gargantuan 16-lane braided interchange. Ritzy Chelsea, Kensington, and Holland Park would all have been shadowed by the new roads. And as we hit midnight, Camden Market would have been torn down to make way for the pillars of eight lanes of highway.

But this never happened. Public disquiet and financial reality grew and grew until, in 1973, a newly elected Labour administration at County Hall made its first act to kill the proposal stone dead. Other than a few urban strays and the isolated segments later stitched into the M25, the only place you will find the Ringways is in J. G. Ballard’s brutal novel Concrete Island. Even Chris Marshall, who has spent almost twenty years reconstructing plans of where the Ringways would have run, describes this alternative London as ‘fascinating to visit but totally unliveable’.

But there is another side to this tale – which means the ghost motorways of London might haunt us yet, in a way we’re not expecting.

Monsters and men

When we think of urban motorways, we imagine cities like Los Angeles, trapped and atomised by 14-lane highways. When we consider the people behind them, we get a mental image of men like Robert Moses of New York, known as ‘Bulldozer Bob’ – overbearing figures who carved up cityscapes and condemned millions to motorized dependency to satisfy their vanity. It seems logical to assume a plan to chain London in motorways would have come from similar tarmac maniacs.

Yet this is far from true. The great road builders of America acted as if they had a duty to speed up the slowing journey of motor cars, and could only do so by adding ever more freeways. By contrast, the transport department of the Greater London Council was doing all it could to tame the rise of the motor car.

In the years in which the Ringways were being developed, the same team had become world leaders in making it hard to drive around London. They brought in London’s first pedestrianized streets and bus lanes. They implemented the world’s largest parking control area and invented the concept of residents-only parking – both ideas designed to discourage car use. They began constructing London’s most recent new Tube line and planned a ‘Crossrail’ twice the size of the line destined to open later in 2022. They pioneered policies which would be considered best practice by their successors today, like integrating land use and transportation planning so as to minimize pressures on the network. They even had plans for a system of road pricing that were so far along that they’d had a draftsman design the permits that would go in car windscreens.

As for Peter Stott – the head of the GLC’s transportation department and London’s answer to Bulldozer Bob – he was a shy engineer who seemed painfully conscious of the damage that traffic was doing to London. As early as 1969 – well before it was fashionable – he was trying to convince his counterparts at the Ministry of Transport that the best use for London’s expensive new system of computer-controlled traffic lights would be to slow traffic down, rather than speed it up, in order to balance the flow of traffic across the city as a whole. He was even so worried about exhausting the national supply of trees suitable for roadside planting that he convinced the council to buy its own tree nursery.

If these men were not monsters, why did they propose such monstrous works? Had they succeeded in their aim and left us to live amongst the consequences, we would be too busy cursing their names to ask. But, in a world where they failed, we have the luxury of a safe vantage point from which to see how their dream came together, and how it fell apart.

The monster that we love

It is no coincidence that the Ringways were designed when they were. We remember the sixties for swinging fashions and long-haired protests; but even stodgy bureaucrats were touched by a spirit of revolution.

Traffic was nothing new in London – people had complained about noise, filth, and danger centuries before the motor car arrived – but by the 1960s there was a sense that the problem was becoming unbearable. The number of vehicles on the road had doubled between 1950 and 1960, on a road system that had barely changed since the days of horses and carts. These roads not only had to deal with London’s traffic, but all the vehicles that wanted to travel through it as well. Cars going from Essex to Oxford, lorries going from Dover to Birmingham, and delivery vans heading to Peckham from Pinner all met and snarled in the same narrow streets.

The problem was destined to get worse. In 1961, officials at the Ministry of Transport made their first official forecast of how that trend might continue. The results horrified everyone who saw them – another doubling of vehicle numbers over the next 10 years; a trebling over 20. For people who thought traffic was unbearable at the moment, this was a catastrophe. Faced with this prospect, officialdom was appalled. To take one example, the 1961 Parker Morris report into ideal housing standards warned that without proper handling, the advent of the car would lead to ‘jungles of concrete, asbestos and tarmac, housing the car but providing an environment of utter inhumanity’. One civil servant, who showed an atypical talent for poetry, described the motor car as ‘the monster that we love’.

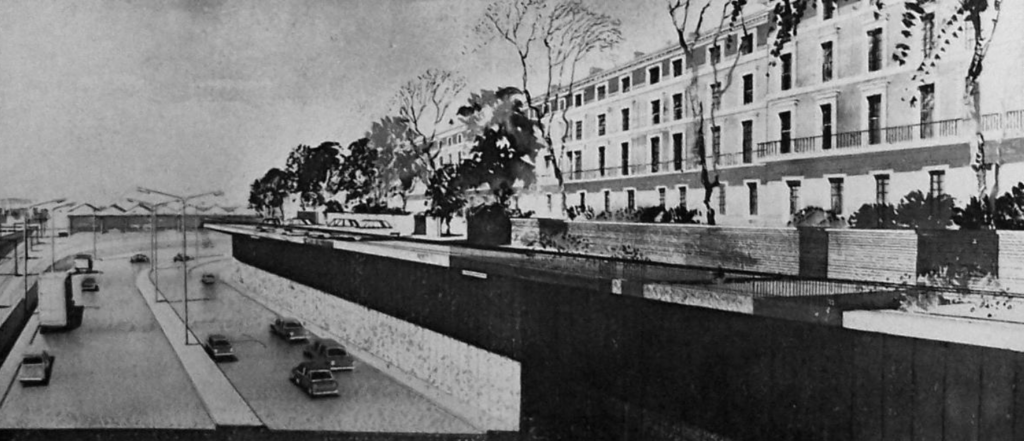

The answer to this coming threat arrived in 1963, through one of the most influential transport plans ever issued by the Ministry of Transport. Known colloquially as the Buchanan Report, it pulled few punches on the growing environmental consequences of motoring (there was even a superb film made to popularize the report that explains what the word ‘environment’ means for the uninitiated). Buchanan himself said that without action, ‘civilized life’ would become impossible, and the answer had to be to rebuild Britain’s cities in such a way that traffic could be banished to purpose-built roads, mostly hidden from view.

Buchanan’s vision was the most startling piece of utopian urbanism ever endorsed by the British state. Case studies talked about raising street levels in places like Oxford Street and rebuilding shopfronts 20 feet in the air on vast pedestrian decks, while cars and buses were banished to an underworld beneath. With traffic decanted to modern highways, neighborhood streets would be designed to completely prevent through traffic and encourage street life, proposing today’s low-traffic neighborhoods half a century early.

It was in this atmosphere that London’s ambitious new council began designing the Ringways. The GLC came into existence in 1965 with a brief to bring London into the modern age, and transport was one of its top priorities. The new council leaders wanted a bold, eye-catching announcement for their first day of existence to show they really meant business. What could be more eye-catching than a decisive plan for taming London’s traffic and restoring the quality of urban life? And, as fortune would have it, the old council’s planners had been working on just such a plan since Buchanan had been published. It seemed too good to be true.

Concrete reality

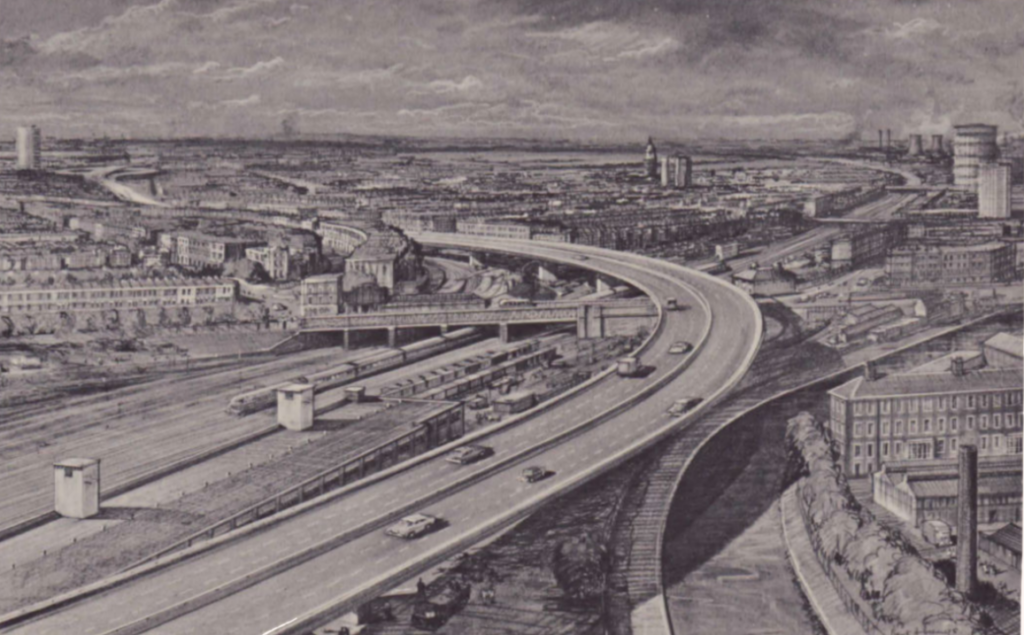

On paper, London’s Ringways were at the cutting edge of environmental design. Modern readers goggle in horror at the sight of Ringway 1, barging its way through historic neighborhoods at the edge of inner London. But this was restrained compared to other proposals. The ‘A ring’ of the 1943 Abercrombie Plan would have put a motorway under the middle of Hyde Park; while a 1963 plan by Peter Hall (later to become Britain’s most famous urbanist and father of the London Overground) would have put a motorway along the northern wall of Buckingham Palace and a major interchange in the middle of Trafalgar Square. Ringway 1, by contrast, had the same diameter as the city of Sheffield, and inside this the planners were clear that public transport must be king.

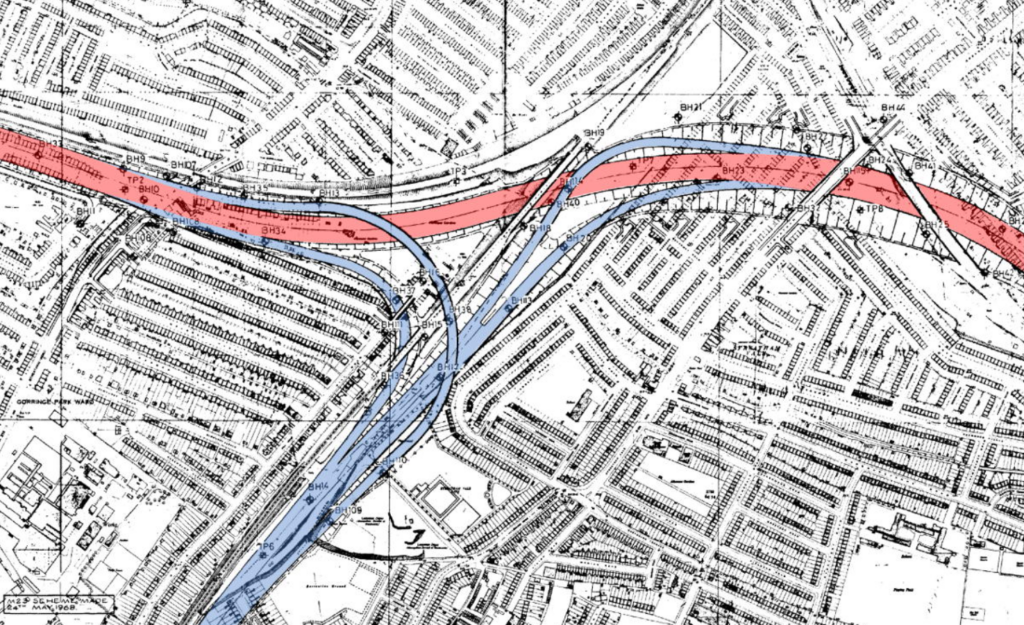

The roads themselves were designed to fit as neatly as possible into the urban fabric – usually shadowing the fault lines set by existing railways – and sunk beneath the earth wherever possible. And in the spaces between the roads, the environmental areas imagined by Buchanan, pedestrians and homes were meant to be protected and with a top speed of traffic no more than that of a bus.

In the years after the initial announcement, the Ringways had broad public support. The winners of the 1967 GLC elections even won votes by complaining that progress was too slow, and that if elected they would make sure it moved faster. But theory could only take you so far when remaking a city. Every inch of the Ringways had to be built in a real city, with disruption and destruction visited on real people. And as more detailed plans began to emerge of where these roads were going to run, the opposition began to coalesce. Public support fell away fast when people found themselves under the hypothetical highways’ shadow.

One of the most prominent examples was Blackheath, a leafy village that had been home to astronomers and lesser royals before it was swallowed by London’s spread in the 19th century. Ringway 1 needed to go through the area, and for the motorway to follow the railway to minimize environmental damage it would have to go through the heart of the village, cutting apart the high street and demolishing row after row of fine Victorian villas. As a result, Blackheath residents began organizing themselves into a ‘motorway action group’.

This kind of behavior wasn’t new in itself. Before the Ringways there had been debates over other roads, where residents’ associations had banded together to oppose a particular road being built in their area (and usually rerouted it into the neighborhood next door). But with the Ringways there was one crucial difference: this wasn’t just about a single area.

The Ringways were a solution to London’s traffic, which meant opposition to them became a London-wide phenomenon. Some critics were in leafy suburbs, such as Barnes, versed in the values of homeownership and urban aesthetics. Others were gritty and proletarian, such as industrial Battersea. When all these groups came together to form the London Motorway Action Group (LMAG) they became a far more troublesome opponent to the GLC. Previously, it might be possible to buy off one group; but as they stood together, the only solution that could satisfy them all was to cancel the Ringways altogether.

There was also a second source of opposition, even more unnerving than angry residents. Even at the peak of enthusiasm for upgrading transport, a significant body of transport experts were deeply worried about road building. A promise to gird London in tarmac was too strong a threat to be ignored out of professional courtesy, so in 1969 these dissenters came together to form the London Amenity and Transport Association. This was a time when transport projects were just coming to be promoted on the basis of cost-benefit analysis, which meant that the members of this group were the first people to check whether the sums added up. Officials were used to quoting figures and having them accepted as fact; now the GLC was put in the uncomfortable position of having its homework marked in public.

The head of the group, J. Michael Thomson, also became the first transport thinker to publicly air an idea that has enlivened opposition to roads ever since – the concept of induced demand, a way of describing the response to an increase in supply of a zero-priced good. In simple terms, the idea was that if you built better roads to remove traffic, without charging people to use them, more people would begin use the new road space and congestion may not fall. In fact, it could even rise. Thomson’s calculations said that building the Ringways would lead to twice as many people traveling by road as before. Instead of liberating the city from traffic, these roads would be the start of a self-fuelling cycle in which roads became jammed, demanding more widening, generating more traffic, and leading to even bigger jams. The only way to win was not to build the two inner rings in the first place.

Climate change

Despite everything, as 1970 began it still seemed as if the Ringways were on their way to becoming reality. Conservatives and Labour backed the project in County Hall, and in the council elections that year the ‘Homes Before Roads’ party managed to gather barely 1 percent of the vote. The designs and diagrams were stacking up, and soon the council would present its new cross-London development plan, which would put the Ringways at the heart of urban development.

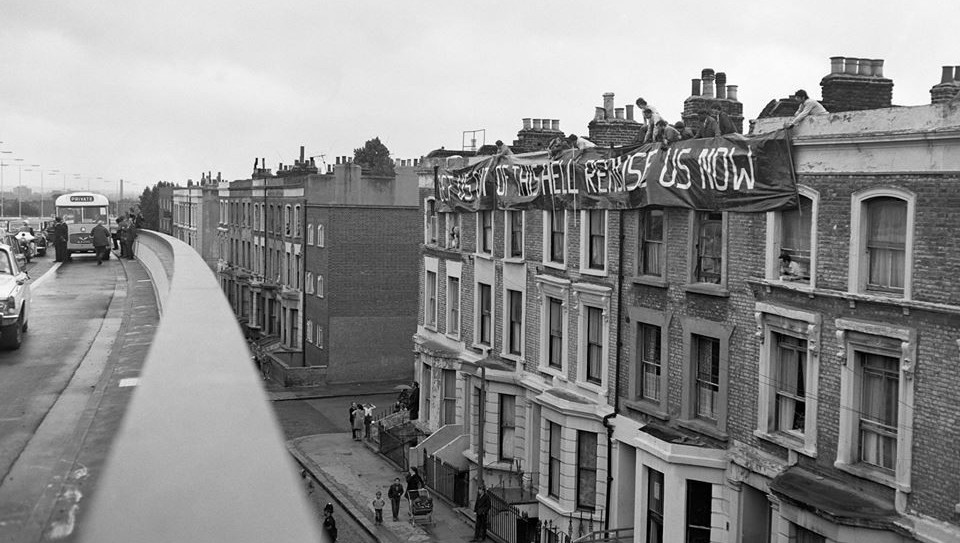

However, 1970 was the year in which everything started to go wrong for the planners. The most dramatic moment came in the summer, with the opening of the Westway – an elevated highway that connected Paddington to Shepherds Bush in west London and filled in a ‘missing link’ that had infuriated engineers for decades.

Although the project pre-dated the Ringways and was not part of the proposed system, it was London’s first experience of the reality of urban motorways. Two and a half miles of stanchions, bridge decks, and surrounding wasteland, it was something even the most ardent brutalist would struggle to love – even before the rooftop roar of traffic began to build.

To make matters worse, opening day was a fiasco. Some neighboring residents lived on Acklam Street, a stereotypical London terrace now stranded so close to the Westway that some inhabitants would endure noise levels similar to having a vacuum cleaner constantly on – and they decided to make their feelings on the project known. As the ceremony to open the road was underway, they climbed onto their roofs and unveiled a massive banner behind the minister reading ‘Get us out of this hell. Rehouse us now’.

A few months later, the minister demonstrated his thanks by paying for the entire street to be demolished. But the reality of the Westway, together with the opening of other controversial urban motorways in other cities, meant that urban road building was no longer an intellectual exercise. Add to this a growing fear of traffic fumes, leaded petrol, and engine noise, and fewer and fewer people were enthusiastic about the prospect of a new urban motorway in their area.

And while this showy disaster was occupying minds, a much more intimate threat was coming for the GLC. During the late 1960s, the government had been toying with the question of how to involve the public more in decision-making. With the growing controversy around the Ringways, it was decided that the cross-London development plan that the GLC was preparing should be subject to a public inquiry, and led by a noted barrister. In effect, the Ringways were now to be put on trial.

The inquiry received 10,000 written objections to the transport elements of the plan, covering everyone from private citizens to massive campaigns. Very few were complimentary. The examination process ran from 1970 to 1972, and big campaign groups mobilized public support and technical evidence that brought the whole plan into question. The GLC staff, who were being cross-examined, had a thoroughly demoralizing experience, and were increasingly sure that their efforts were doomed.

But none of this helped with one rather large outstanding question – how would London pay for its new roads? At around £24 billion in today’s money, there was no way that this could be raised from local taxation; and central government’s funds became tighter and tighter as the economy slowed in the early seventies. Any hope of funding went from remote to ridiculous.

The political tide was clearly turning. Although the Conservative leader in County Hall was so personally tied to the Ringways there was no retreat for him; the Labour party, which was in opposition, found it easy to change tack. While the previous Labour administration had designed and approved the Ringways, a new generation of Labour leaders was coming up in boroughs hostile to the road plans – calling it the biggest environmental disaster in London since the Great Fire. In 1972 Labour promised to cancel the two inner Ringways and their linking roads if it won the next election. When they duly did, their first action on reentering County Hall was to pull the plug.

Future tense

Today, we mostly remember the Ringways as an exercise in madness, but the business of reshaping the city for environmental goals is anything but. It may seem like sacrilege to suggest that environmental campaigners can take lessons from elevated highways, but there are similarities worth considering. Tackling climate change is as widely supported as taming traffic once was. Rebuilding our cities to eliminate emissions might be just as disruptive. The political structures that undid the Ringways are largely still in place. Seen in those terms, the Ringways aren’t just a narrow escape for London – they offer a map of dangers ahead.

The Ringways are also something of a foundational moment for British NIMBYs. Plenty of people had raised their voices against the spread of streets, houses, and railways in the past, and some planning controls were brought in with the 1948 Town and Country Planning Act. Yet officialdom was perfectly happy designating a green belt with one hand and creating another half-dozen new towns with the other. Public opposition, where it came, was desultory and pessimistic. When Whitehall had made up its mind, the expectation was that you could grumble but you could never expect to dissuade them.

The defeat of the Ringways marked the first time that the planners had been publicly defeated. It showed that great plans for recasting urban space were not some unanswerable edict from on high: they were political proposals that could be successfully fought against. In a countercultural age, this protest was practical and fashionable in equal parts: not only was there the inspiration of seeing the biggest road plan of all and the biggest and most powerful council in the land stopped, but veteran opponents shared their secrets in how-to guides like J. Michael Thomson’s Motorways in London.

More subtle, but perhaps more serious over time, it also showed the unintended consequence of those victories. When the Ringways failed, they didn’t just stop the proposed road. The whole of the proposed Greater London Development Plan – the largest ever planning proposition made in British history tying up transport, land use, economic planning, environment, and more – also died with it. It could even be argue that the GLC, which was set up to enable this kind of unified planning, never really recovered from the blow; either way the council was abolished 13 years later.

And the planning inquiry tactics used to halt the Ringways have been used to delay housing plans, railways, reservoirs, renewable power stations, and much more besides. You need not be a fan of urban motorways to wonder whether these tools have been used consistently for good. Since the Ringways failed, Britain has designated no new towns; has built only one nuclear power station out of at least 13 proposed; and has generally decided that it is easier to build a wind farm 50 miles out to sea than it is to get it through a local planning inquiry.

What might these lessons be? The first is that visions are fickle things. They begin life as tools for mobilizing people to action and helping coordinate them to deliver a common goal – powerful achievements when the alternative is doing nothing. But the problems quickly start to mount up once action is underway. Everyone could sign up to a plan to contain traffic; but when it becomes clear that this would mean huge disruption, costs, and environmental drawbacks, that consensus evaporated fast. The promise of a better life in a few decades’ time pales into insignificance when set against the fear of a motorway being built at the bottom of your garden. We can see the same dynamic playing out today between the principle of zero-carbon energy and the spirited opposition to wind farms and nuclear plants.

The second is that opponents are much more dangerous in large numbers. Most previous local campaigns against road schemes collapsed into local feuding about whose back garden should be sacrificed. The genius of the anti-Ringways campaigners was to unite disparate local campaigns into a larger force. This didn’t just mean more voters at their beck and call; it meant that individual local campaigns joined up into a greater cause. Together, their cause was no longer a matter of local concern but national interest; and by fighting against something so large, groups like LMAG made it harder for the GLC to cut deals to satisfy local concerns. We can see a similar strategy being played out today under the banner of ‘net-zero scrutiny’.

Third, though we tell the story of the Ringways as the defeat of a roads plan, the truth is that the deck was always stacked in favor of doing nothing. To actually build the roads, the planners needed designs, money, political will, and local acquiescence – and needed to keep them in place for a quarter of a century. The greater miracle in some ways is that the promise lasted as long as it did. While that’s mostly a relief, the same was equally true of the GLC’s other blockbuster transport plan – their early system for road pricing. After the Ringways were canceled, the new administration asked for advice on how to achieve their target of reducing car traffic by a third. Officials duly presented plans for their pricing scheme, and watched as it was buried just as deep as the Ringways. No traffic reduction ever came, and together with the rest of the world Londoners just became inured to traffic. The real winner was inertia. It speaks volumes that today we struggle even to believe that people in the 1960s thought that the threat of 40 million vehicles on UK roads (roughly the number there are today) was a reason for ripping London to pieces.

But there is one last lesson worth taking away. If the Ringways’ creators were afraid of what traffic would do, they might not have been so appalled to see what 2022 would be like. Despite abandoning its roads, London does possess one of the world’s best public transport networks; Londoners who drive into the central area are freakishly rare. More broadly, car engines are around 10 times quieter than they were; air pollution, though a serious problem, has declined to 20 to 30 percent the level of 1970 even after factoring in all those extra cars. A ring road, buried deep in the countryside, managed to subtract all that through traffic from London’s roads. ‘Civilized life’ has turned out to flourish rather nicely under these conditions.

The policy measures that made this happen were nothing like the Ringways – big, bold, and high-risk. London’s buses and Tubes were revived by patient managerialism that focused on providing the public with a service they’d choose to use, rather than glitzy new capital projects. The car was partly scared away from the center by the introduction of a congestion charge in 2003, but much more by the sheer expense and impracticality of finding anywhere to park. Vehicle emissions and noise standards are set to take effect over decades, and are so dull that even post-Brexit Britain has no plans to do anything other than copy its neighbors. Not a single person working on these policies would think they were saving London; but quietly, year by year, they did.

So as we prepare to remake the city to deliver huge changes, perhaps the Ringways should inspire us to hold back on the grand visions. Even in the utopian sixties, no human settlement could be reduced to a sheet of blank paper and redesigned from first principles. Great battles for the souls of the city make for great stories, but the real tools of change turned out to be small, subtle, and slow – policies that understood the power of turning a 1 percent a year change into 2 percent.

As for the Ringways, with the exceptions of a few isolated pieces of tarmac, all we have left of them are riddles and a few blocks of concrete. Like a suburban Ozymandias, they await the passing traveler with a warning: look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair!