It has taken almost 60 years to bring traffic congestion pricing to New York. This is the story of how politicians and advocates built the coalition it needed to finally happen.

In the 1980s, New York’s Department of Transportation held a series of public meetings open to any interested New Yorker on what to do about the city’s chronic traffic problem. ‘This older, professor-like guy attended these meetings, by the name of William Vickrey, and he kept pestering me to do congestion pricing’, said Sam Schwartz, then an official at the Department of Transportation. ‘I hadn’t heard that term before.’

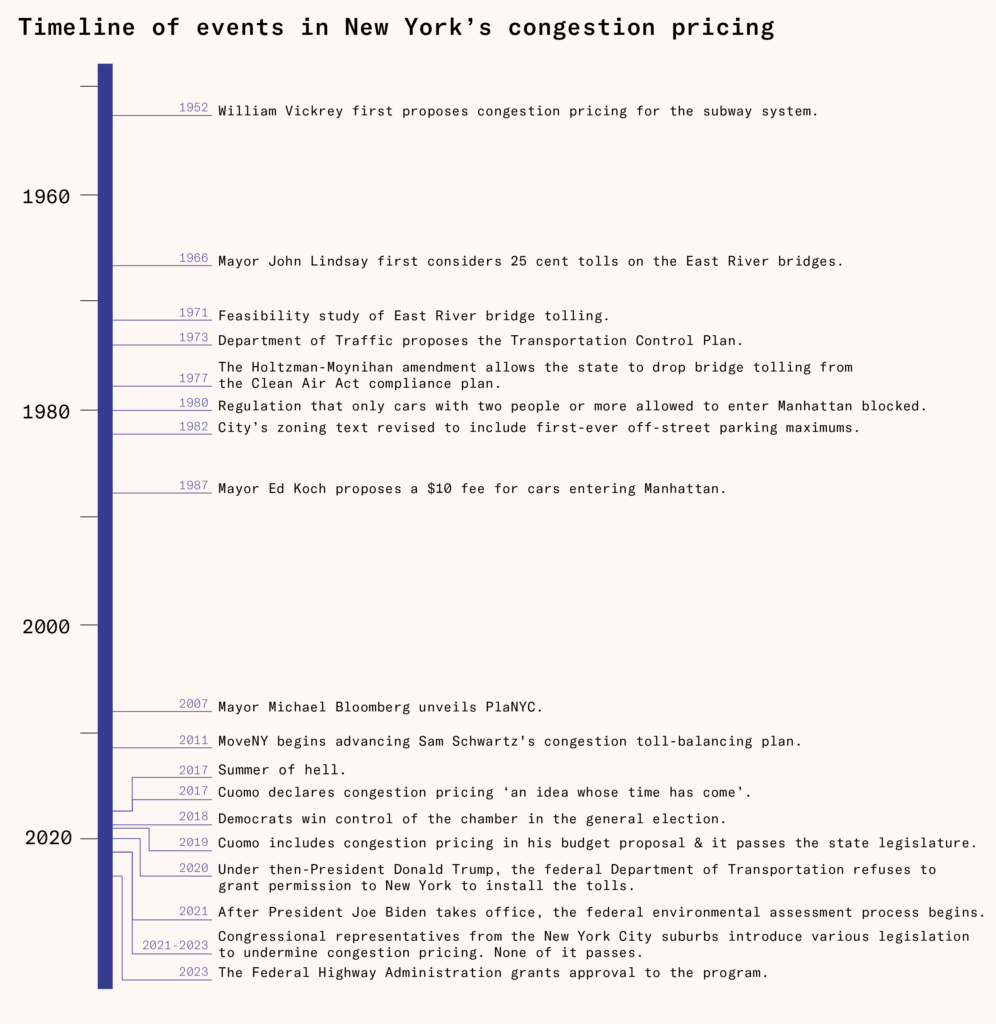

The idea of congestion pricing for New York City dates back to 1952, when it was first proposed by William Vickrey, a young academic at Columbia University who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in economics. It was an idea ahead of its time that would take decades to gain traction. This is the long and tortuous story of how, more than 70 years later, Vickrey’s congestion pricing vision may be about to become reality in New York City.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

The long road to congestion pricing

New York, by far the largest and densest US city, is also the most choked by congestion. The city’s drivers lose an average of 112 hours per year to gridlock, according to the Dutch location technology firm TomTom. The next-worst US city, with 89 lost hours annually, is Los Angeles.

The costs of this inefficiency are enormous. By 2016, according to the Partnership for New York City, a business advocacy group, one third of the 3.6 million people who traveled into Midtown and Downtown Manhattan each day were in automobiles, crawling along at less than 12 miles per hour during rush hour. The group estimates that traffic directly costs the regional economy more than $13 billion a year in lost hours and extra fuel, equivalent to more than twice the annual budget of the New York Police Department.

The knock-on effects are even greater. Cities are rich because people become more productive when they can work in a larger and deeper pool of people. Cities with slow transport have a lower effective size – although a lot of people live in the metropolitan area, it is difficult to get around to work with one another. The lack of a reliable connection to the center could be making those living in outer suburbs take worse jobs than they might otherwise get, leaving potentially tens of billions of dollars in productivity on the table.

When London introduced congestion charging in 2003, total traffic fell 18 percent, increasing road speeds and cutting air pollutants such as particulates and nitrogen oxides. Civic organizations have long advocated for similar policies in New York. By dedicating the revenue raised to bolstering New York’s struggling mass transit system, they argue, the program could allow New Yorkers to move faster on both the roads and subway.

Under state law, New York City cannot impose taxes or tolls without explicit state permission. In 2014 for example, Governor Andrew Cuomo and state legislators repeatedly blocked Mayor Bill de Blasio’s proposed millionaires’ tax.

Previous congestion pricing proposals met a similar fate, failing to get through the state capitol. But Cuomo was eventually persuaded that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which runs the subways, buses, and some suburban commuter rail lines, needed a new source of revenue. In 2019, at Cuomo’s behest, congestion pricing was passed into state law with a mandate to raise one billion dollars per year for the MTA’s capital improvements program.

Five years later, the system is still not in place, and New York’s traffic remains as bad as ever. While it is scheduled to roll out on June 30th, 2024, legal challenges could yet derail it.

‘I’m giving it a 70 percent chance at this point’, said state senator Liz Krueger, a Democrat from Manhattan who has supported congestion pricing since Mayor Michael Bloomberg first proposed it in 2007.

These delays in implementation are minor compared to the almost 50 years that elapsed between the first time the New York City government proposed congestion charges and when the state finally authorized them. Congestion pricing didn’t pass the New York State legislature until its fifth attempt.

New York’s long, winding road to congestion pricing contains lessons for other cities around the world that may want to follow suit. You can’t take the politics out of policy, you need to offer the communities that will be paying more something in return, and that something must involve a cut of the revenue rather than merely easing traffic.

The beginning

In the early 1970s, New York City – especially its densest borough, Manhattan – had a problem. In fact it had many problems, including rising crime, white flight, and a brewing fiscal crisis, but there was a tangible and inescapable issue in the air: pollution caused by the growing volume of motor traffic.

The federal Clean Air Act of 1970 required states to develop plans to meet national ambient air quality standards. Brian Ketcham, an automotive engineer in the New York City Environmental Protection Agency set up an automotive testing lab in Brooklyn that measured emissions from different types of vehicles and tested pollution control equipment. Ketcham concluded that traffic in New York’s central business district was so heavy that regulating tailpipe emissions wouldn’t reduce particulate pollution enough to bring the area’s air into compliance. Another approach would be needed.

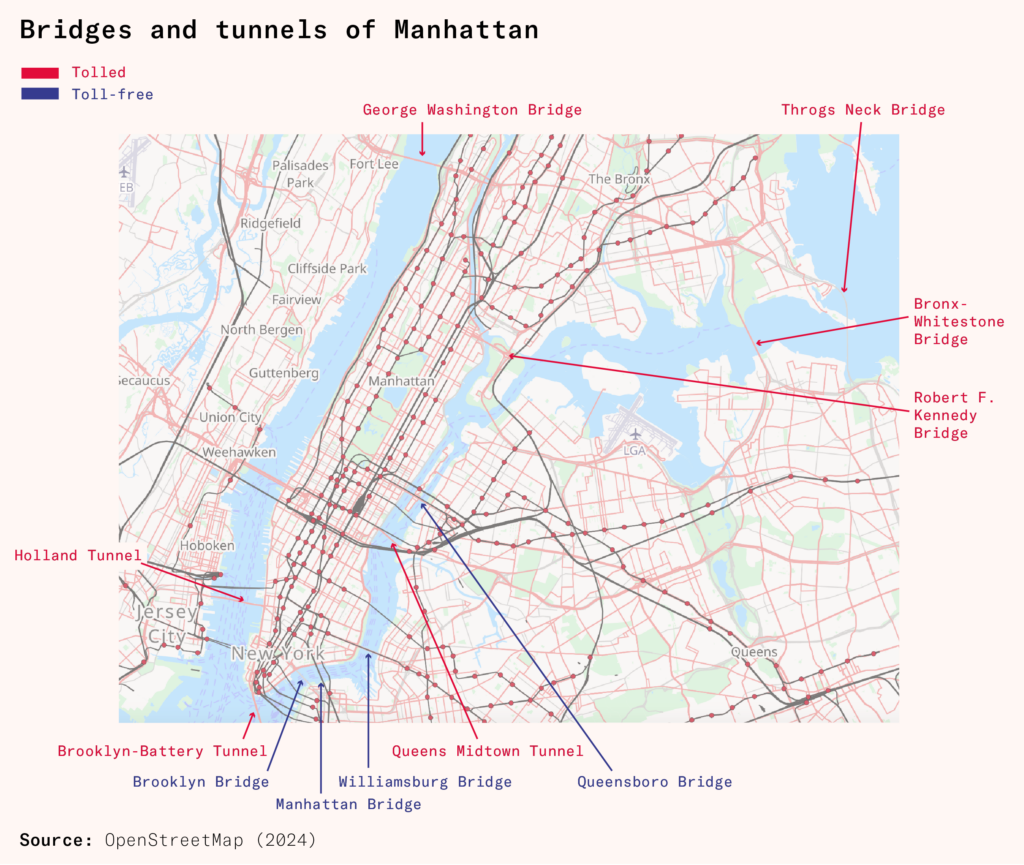

Manhattan is connected to the outer boroughs across the East and Harlem Rivers and to New Jersey across the Hudson River by a series of bridges and tunnels, but for historical and bureaucratic reasons only some of these require drivers to pay a toll. The Hudson River crossings such as the George Washington Bridge and Holland Tunnel are tolled, as they are manged by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, a quasi-governmental agency that raises money through user fees.

Another such agency, MTA Bridges and Tunnels, operates and charges for using the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan), the Queens Midtown Tunnel (Queens to Manhattan), bridges between Queens and the Bronx such as the Throgs Neck and the Bronx-Whitestone, and the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (also known as the Triborough, because it connects Queens, the Bronx, and Manhattan).

But bridges managed by the New York City Department of Transportation connecting outer boroughs to Manhattan, such as the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges – which span the East River – and the bridges crossing the Harlem River between Manhattan and the Bronx, such as the 145th Street Bridge and the Madison Avenue Bridge, are toll-free.

In the first of many abortive attempts at charging traffic, Mayor John Lindsay raised the idea of tolling the East River bridges in 1966, but his administration soon backed off amidst criticism from the auto lobby. In 1971 Lindsay tried again, ordering a feasibility study of bridge tolls, aimed at raising revenue that would help keep subway fares low. The state legislature rejected that proposal and most of the city’s powerful Board of Estimate also opposed it.

Ketcham and his colleagues went on to develop the 1973 Transportation Control Plan to reduce the number of cars coming into the city center. The plan proposed a range of measures, such as creating taxi stands to reduce the time taxis spend driving around looking for fares, but the most significant proposal was to place tolls on the bridges that span the East and Harlem Rivers, connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. This would reduce traffic from the three most populous outer boroughs and the city’s northern and eastern suburbs.

Lindsay embraced the proposal that same year, and New York City’s first official congestion pricing plan was born. The state incorporated the measure into its federally mandated plan to bring local air quality into compliance with the new federal standards.

But the federal government was divided against itself. While the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was demanding congestion pricing, the Department of Transportation filed a suit to block the tolls, arguing that local governments cannot toll bridges that the federal government helped fund. In January 1977, the federal appeals court rejected that argument.

Lindsay’s mayoral successor, Abe Beame, opposed the bridge tolls, calling them ‘an undue burden on drivers’, but by then they had been incorporated into the state’s official plan to comply with federal law, so the city was legally bound to adopt it.

‘Nothing could stop it short of an act of Congress, and in 1977 there was an act of Congress: the Moynihan-Holtzman amendment’, said Sam Schwartz, the former chief engineer of the New York City Department of Transportation. The May 1977 amendment to the Clean Air Act, sponsored by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, offered New York State a way of dropping congestion pricing, replacing the East River tolls with alternative means of reducing car traffic, such as improved public transportation. This was welcomed by Governor Hugh Carey, the newly elected Brooklyn Democrat who had opposed the tolls, saying they would increase pollution near the toll plazas. A report released earlier that month by the New York State Departments of Environmental Conservation and Transportation also argued tolls would place an excessive cost burden on businesses in Manhattan.

New York and the federal EPA agreed to pursue an alternative plan to discourage driving and the congestion pricing proposal died.

Some architects of New York’s congestion pricing scheme believe the New York policy was initially too far ahead of its time. Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing system arrived in 1998. The Congestion Charge in London operated from 2003. Stockholm’s congestion charge was introduced in 2006, and Milan’s Ecopass in 2008.

In the 1970s, ‘there was no such thing as electronic tolling’, noted Charles Komanoff, an energy policy analyst and, in recent years, prominent congestion pricing advocate. ‘So tolling the bridges would have required toll booths.’

‘The specter of mile-long queues back into Brooklyn and Queens that were going to be pumping exhaust gas in the interest of reducing emissions was too self-contradictory.’

A few smaller ideas to encourage alternatives to automobiles were eventually adopted, including the removal of some on-street parking spaces in Midtown and the expansion of bus and bicycle lanes. In 1982, the city’s zoning text was revised to include its first-ever off-street parking maximums.

But Americans continued their decades-long shift from riding trains to driving cars. According to data from the Eno Center for Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration, Americans drove 6,767 miles per person in 1981. That rose steadily to 9,937 miles per capita miles per capita in 2019. Although New York State – with more than half the population concentrated in New York City and its suburbs – has the lowest vehicle miles per capita of any state, it rose there too, from 4,504 in 1981 to a peak of 7,302 in 2006, before dipping to 6,316 in 2019. In Manhattan, they continued to move very slowly.

Second and third tries

In 1978 the newly elected mayor, Ed Koch, appointed a forward-thinking deputy commissioner, David Gurin, to the city’s new Department of Transportation, who in turn recruited Sam Schwartz, later a leading proponent of congestion pricing, to his team. Gurin and Schwartz promptly took the then-revolutionary step of replacing an auto lane on the Central Park and Prospect Park ring roads with bike lanes.

‘[It was] the first time car lanes were removed for bicycles’, Schwartz recalled.

When the Transit Workers Union went on strike in 1980, Koch tasked Gurin’s team with devising a plan to manage the expected spike in car traffic from commuters whose trains and buses weren’t running. A previous transmit strike in 1966 had led to hours-long car backups and devastating economic consequences. In writing the plan, Schwartz coined the term ‘gridlock’.

The department barred cars with fewer than three passengers from taking major highways in the city or entering Manhattan south of 96th Street (about two thirds up the island, most of the way up Central Park); created bike lanes on East River bridges; and initiated ride-sharing in taxis for the duration of the strike. Together these measures worked, preventing the chaos of earlier strikes.

‘After that, the mayor said, “You guys were heroes, you gotta come up with some other strategies to reduce the traffic congestion”’, Schwartz said. ‘I came up with a plan which was a mini-congestion pricing plan that could be implemented overnight.’

Three crossings across the East River are tolled – the Battery Tunnel, the Midtown Tunnel, and the Triborough Bridge – and four crossings are toll-free; the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensborough Bridges. From 6am to 10am, only cars with two people or more would be allowed to enter Manhattan via the free crossings.

‘We passed a city regulation in late 1980 and we were promptly sued by the Garage Board of Trade, which practices congestion pricing in all its parking facilities’, Schwartz said, referring to the fact that the most centrally located garages charge the highest prices. The local chapter of the American Automobile Association also sued. The state judge sided with the plaintiffs, and Koch declined to appeal the ruling.

At this point, the Department of Transportation decided to hold public meetings, inviting New Yorkers to say what they would do about the congestion crisis. It was at these meetings that William Vickrey pressed the case for congestion pricing.

Partly due to Vickrey’s influence, and with the city again on the precipice of its air quality being in violation of federal law, Koch proposed a ten-dollar fee for vehicles entering Manhattan south of 59th Street (the southern end of Central Park, the northern border of Midtown Manhattan)

in 1987.

Once again the backlash was severe. ‘One thousand businesspeople showed up to denounce it on the steps of City Hall’, Schwartz said. ‘They called it “draconian measures.”’ Under pressure from the business community and organized labor, Koch shelved the plan.

The imperial mayor issues a demand

On Earth Day 2007, Mayor Michael Bloomberg unveiled 127 initiatives to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, but most people remember only one: congestion pricing. Pointing to London’s successful adoption of a congestion fee in 2003, and with an endorsement from UK prime minister Tony Blair, Bloomberg suggested an eight-dollar fee for cars and $20 for trucks entering Manhattan south of 86th Street on the borough’s Upper East and West Sides, with the revenue – an estimated $400 million per year – going to the mass transit system.

Given Americans’ famous commitment to their cars, not many US politicians would have had the nerve to propose congestion pricing at a time when the idea was still novel to many. But Bloomberg was a unique political animal – a multibillionaire who could outspend opponents by a factor of 14. He felt liberated to do as he saw fit, even if it risked provoking a powerful constituency.

This was one policy the mayor could not institute without the state legislature passing enabling legislation, however. And while he was adept at drumming up support in the city’s nonprofit and business sectors, he failed to do so in the state capitol. Bloomberg – despite his liberal views on social issues and the environment – had run as a Republican to avoid the more competitive Democratic primary. He bankrolled Republican state senate campaigns, making a $500,000 donation in 2006 to help win approval for his policies from state legislators in Albany, the New York State capital. But Republicans from the suburbs did not want to upset constituents who drove into the city. So congestion pricing needed Democratic votes to pass the Senate and the heavily Democratic Assembly.

While measures to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions would appeal to some on the left, Democratic moderates, representing seats in the outskirts of the five boroughs of New York whose constituents would be the ones paying the new tolls, were largely skeptical. From the beginning they argued that the fee would be regressive, deriding the idea as an elitist plot to benefit rich Manhattan at the expense of the working-class outer boroughs.

‘The middle class and the poor will not be able to pay these fees and the rich will’, said Richard Brodsky, a Democrat from suburban Westchester County who chaired the Assembly committee overseeing the MTA.

It is true that congestion pricing is regressive in the same sense that a sales tax is regressive: any flat fee consumes a larger share of a smaller salary. But what about a sales tax that only applies to a product disproportionately consumed by the rich? That’s what congestion pricing is, at least in New York City.

Of commuters going into Manhattan’s traffic-clogged center, 85 percent use mass transit. The poor overwhelmingly don’t drive into Manhattan, because the poor in New York mostly don’t drive at all, and they certainly don’t drive into a borough where parking at a street meter costs more than five dollars per hour and garage parking costs several times that. Midtown garages typically cost more than $20 for one hour and around $60 per day.

Nonetheless, Bloomberg failed to gain sufficient support in either chamber of the legislature. ‘They didn’t do their politics, the Bloomberg people’, Schwartz said.

Senate Democrats, resentful of Bloomberg’s efforts to keep them in the minority, were in no mood to do him any favors.

‘He came to Albany, one day, and said, “Okay, I need your votes”’, said Senator Krueger. ‘And the response was, “You just spent a fortune against me, or my colleague or my friend, to keep us out of here. Why the hell would we be giving you votes, when a lot of the members were not supporters of congestion pricing, or came from a part of the MTA region where it was a much harder lift for them to be in favor than it was for those of us in Manhattan?” And yet he was just assuming that people who had no reason to would do him a favor.’

Legislators found Bloomberg arrogant and presumptuous in their meetings with him, as he demanded they vote for the bill just three days after it had been unveiled and argued the city would lose a $350 million federal grant if it wasn’t passed immediately.

‘At one point, the mayor was furious and yelled, “Well, if you’re not going to vote for this bill today, you’re gonna have to come up with $350 million for New York City!”’ Krueger recounted. ‘The whole thing had gone down the tubes. I, who has been known to mouth off occasionally – and again, I was a supporter [of congestion pricing] – yelled, “Mr. Mayor, we make $49,000 per year. You’re the only person who can write a check for $350 million; you better get out your checkbook.”’

‘If the mayor came in with one vote, he left with none’, state Senator Kevin Parker, a Brooklyn Democrat, told The New York Times.

Yet this failure offered a valuable lesson for future congestion pricing efforts: to succeed politically, the policy’s supporters would have to carefully build support in the legislature.

A decade in the wilderness

After Bloomberg’s failed attempt, advocates strove to keep the idea of congestion pricing alive. The coalition of some 140 labor, environmental, and business organizations that supported Bloomberg’s plan, known as Campaign for New York’s Future, gradually disintegrated, but many continued individually to develop their ideas.

Around 2011, Sam Schwartz, the former Transportation Department official, linked up with the policy analyst Charles Komanoff and Alex Matthiessen, an environmental activist, to begin advancing a new proposal.

Judging that the reason suburban and outer-borough legislators largely opposed it was because it would raise fees on their constituents, they published a proposal called Move NY, intended to ameliorate those concerns by reducing the costs constituents faced elsewhere.

At that time, the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge from Brooklyn to Staten Island cost truck drivers between $22 and $147 depending on how many axles their vehicle had and how they paid. This created a perverse incentive for truckers traveling between Long Island and New Jersey to go through Manhattan rather than around it. So Move NY proposed using some of the revenue generated from tolling the East River bridges to reduce other tolls, such as that on the Verrazzano-Narrows, The rest, Komanoff calculated, could finance $10 billion worth of mass transit improvements.

Many of the groups involved in the Campaign for New York’s Future backed Move NY, helping Schwartz, Komanoff, and Matthiessen to promote the concept in the media and among elected officials.

‘We got every single editorial board to endorse the Move NY plan, including the New York Post’, Schwartz said, referring to the right-wing, Murdoch-owned tabloid.

Yet, although bills were introduced in Albany, including by Staten Island Republicans eager to reap the benefits for their borough, the leadership never brought them to a vote, suspecting they lacked the support needed to pass. What gave congestion pricing another shot was instead a desperate need for subway funding.

Cuomo’s MTA

A political strategy to get congestion pricing passed in Albany was going to need a more effective advocate than Bloomberg – someone like Governor Andrew Cuomo, whom Albany insiders referred to as an ‘800-pound gorilla in the room’ because of his dominant role in state lawmaking. But Cuomo, a muscle car aficionado who had grown up in Queens and lived in suburban Westchester before taking office in 2011, was initially opposed.

Meanwhile, the need for new revenue for the MTA was becoming increasingly urgent. The New York City subway began operating in 1904, and a century later its infrastructure was aged and outdated. Annual ridership grew from one billion in 1997 to 1.7 billion in 2015, thanks to the introduction in 1997 of free transfers between subways and buses, the advent of weekly and monthly unlimited MetroCards, population growth, sharply declining crime, and fast-growing tourism. But, because fares were priced lower than the cost of operation, these additional riders placed a strain on the antiquated system, and on-time performance plunged.

For some metro systems, growing ridership numbers would have been a boon, not a burden. London’s Underground charges a weekly maximum of £78 ($98), and recovers more than 100 percent of its operating costs through fares, making a small profit that is used to fund other transit such as the bus network. By contrast, NY subway fares cap out at $34 weekly, and they cover only 24 percent of its costs, relying on continual taxpayer subsidies to keep going. Thus, more customers can actually mean a more difficult job. Average delays per month increased from 20,000 in 2012 to more than 67,450 in May 2017. And whereas 85.4 percent of subway trains finished their route within five minutes of their schedule in 2011, only 66.8 percent did in 2016.

In response to these deteriorating conditions, a grassroots group called the Riders Alliance started a campaign to raise public awareness of the situation within the MTA. This started with the fact that the MTA is controlled by the governor, and thus he – and not the mayor – was responsible for the state of the subway.

In 2017, as the group pushed for Cuomo to find new revenue to fix the subway system, the transit crisis exploded in the public consciousness during the so-called summer of hell. Emergency repairs at Penn Station caused major disruptions to suburban commuter rail lines and the subway’s service troubles seemed to crescendo.

The Riders Alliance created the hashtag campaign #CuomosMTA, and the phrase stuck in New Yorkers’ minds, prompting Cuomo to finally take steps to address the crisis. He brought in new leadership at the MTA and declared that congestion pricing was ‘an idea whose time has come’.

‘We are on the trajectory that was launched in that moment’, Komanoff said. ‘And that happened only because of the Riders Alliance and the whole constellation of transit advocates.’

Thereafter, ‘our funding proposal, which had been an all-of-the-above approach, really narrowed to congestion pricing’, said Danny Pearlstein, spokesperson for the Riders Alliance.

Cashless tolling, in which cars are electronically charged as they drive past a camera, had become widespread in America by 2017, when the state government created the Fix NYC task force to find solutions to the city’s transportation woes. Taking advantage of that technology, states from Florida to California had been creating express lanes that allow only multi-passenger vehicles, or charge a fee for single drivers. The idea is to reduce traffic for everyone by incentivizing carpooling. Some even charge a flexible surge price at peak times to any driver. (Opponents deride them as ‘Lexus lanes’ for those who can afford them, while advocates like Tennessee Republican governor Bill Lee prefer the term choice lanes’.)

In December 2017 Fix NYC, the new task force, recommended charging $11.52 for cars and $25.34 for trucks entering the central business district, south of 60th Street, during peak hours. But the state budget passed the following March still did not include congestion pricing, although it did create per-trip fees of $2.50 for taxis and $2.75 on ride hailing apps in the congestion zone south of 96th Street, with the revenue going to the MTA.

The 2018 election boosted congestion pricing’s prospects. In the years since Bloomberg had left the scene, growing partisan polarization had made Republicans more uniformly opposed to congestion pricing, as they hung on to control of the chamber by a margin of one. In a backlash against President Donald Trump, progressive Democrats turned out in droves and not only ousted the Republicans but also defeated several suburban moderates in the Democratic primaries. In many cases, opponents of congestion pricing were replaced by enthusiastic supporters.

In 2019, Cuomo included a congestion charge in his budget proposal. The outside game of the activists was now complemented by the governor’s inside game. In New York’s legislative process, the state budget is a large omnibus bill that contains many disparate policies and the governor is a powerful actor in crafting the law.

‘The first time that [congestion pricing] seemed to have legs at the state level was this plan, as it came to be, as part of the budget process in 2019’, said Assembly Member Ed Ra, a Republican from suburban Long Island. ‘When Governor Cuomo was really focusing on something, he usually found a way to get it across the finish line.’

Larding the state budget with tangential measures is standard operating procedure in New York. The 2019 budget bill included a range of criminal justice reforms such as the elimination of cash bail for minor offenses.

Including congestion pricing in that package helped it pass in two ways. First, opponents such as Ra say that the debate over hot-button issues like bail reform distracted the public from congestion pricing and tamped down opposition. Second, legislators could vote for the budget while distancing themselves from congestion pricing by saying their vote was cast to support other programs.

‘For those people who were like, “This will be very unpopular at home, how will I deal with it?”, the answer was conveniently, and politically, designed such that you’re not taking a vote on it, you’re taking a vote on budget bills that have a huge number of other things in them that you really want to vote for and need to vote for,’ Senator Liz Krueger said. ‘So you can even go home and say, “Well, I didn’t like this part, but I had to vote for this because it had A, B, C, D that we had to get done.”’

Another clever maneuver by Cuomo’s team was to link the proposal to an MTA capital improvement plan that would require enough revenue to raise $15 billion through selling bonds, which works out at about one billion dollars in revenue per year.

‘They focused on the gain, not the pain’, Charles Komanoff told me. ‘Nobody knew what the toll would have to be, but rather it would fund $15 billion in capital improvements. So it was all positive and no negative.’

In this case, the gain would include everything from better on-time performance and more reliable air-conditioning for trains and buses to elevators for disabled access to subway stations.

But some cried foul. According to state legislators on both sides of the issue, Cuomo personally lobbied legislators to vote for congestion pricing with promises of improving bus or other transit service in areas where the subway doesn’t run.

‘Andrew Cuomo twisted arms for people to vote for it, on the false promise that they were gonna get all these goodies for their district: all these extra bus lines that never materialized’, said Assembly Member David Weprin, a Democrat from the outer reaches of Queens. ‘It was all lies, basically.’

Weprin, who voted against congestion pricing, also believes the transit service won’t be meaningfully improved because the MTA, a notoriously inefficient bureaucracy, won’t put the money to good use. ‘The more money you give to the MTA, the more money they’ll waste’, he said.

There is at least some truth in this assessment. New York City has the highest construction costs in the United States, due to factors such as high labor costs and more expensive liability insurance, but the MTA’s construction expenses are egregious even in context. It costs three times as much to build a subway station in New York as it does in London or Paris, thanks to extravagant design choices, extensive environmental reviews, and inefficient union work rules. The recently completed Second Avenue subway line cost six times as much per mile of track as expansions of the Paris and Berlin subways. It should be noted, however, that the MTA’s capital spending plan is not primarily focused on building new stations and subway lines. It is mostly earmarked for replacing and upgrading existing infrastructure to keep it going.

Cuomo did not respond to an interview request submitted to his spokesperson, but Senator Krueger said that while she believes Weprin’s account, the specific transit improvements in the outer boroughs that she remembers being in the deal have been fulfilled.

‘One part of the deal was four new Metro-North stops in the Bronx, and that’s been made good on’, she said, referring to the commuter train line serving New York’s northern suburbs. Construction began on the promised stations in areas of the Bronx lacking subway service in 2022. ‘The ones I’m familiar with, they actually have made good on’, she said.

The 2019 budget included the creation of a congestion pricing system for entrance to Manhattan south of 60th Street, but it left the details of how much to charge and gave some discretion of who to exempt to the Traffic Mobility Review Board, which the MTA would assemble. This board was tasked with ensuring that the program provided a minimum of $15 billion in funding for the MTA’s Capital Program, with 80 percent of the funds dedicated to the Staten Island Railway, New York City Subway, and MTA Regional Bus Operations, while ten percent would be given to the Long Island Rail Road and ten percent to the Metro-North Railroad. The law mandated exemptions for emergency vehicles, vehicles transporting people with disabilities, and for drivers who cross a bridge but stay on a highway until they are north of 60th Street. The law also required people living in the congestion zone who make less than $60,000 a year get a tax rebate for the cost.

But one group did not see any relief. Drivers from New Jersey and Staten Island already pay high tolls on bridges and tunnels. They would now have to pay the congestion charge on top of existing fees. This triggered intense opposition from those areas, but New Jersey does not get a vote in the New York State legislature, and the support of the mostly Republican representatives of Staten Island – New York City’s least populous borough – was not needed now that larger and left-leaning Democratic majorities could provide the votes.

Leaving it up to a board that doesn’t have to face the voters was a clever move, because legislators were more comfortable voting for the program’s creation without having to take a position on whether, say, cops or firefighters who commute to work in Manhattan would be exempted from the fees.

‘The devil’s in the details, but those wouldn’t be up to the legislature’, Senator Krueger said. ‘It was more politically viable to people who didn’t want to be seen as having anything to do with those decisions.’

So at last, after 50 years, New York had become the first American state to pass congestion pricing.

The saga continues

You might assume that once a law is passed the program will be implemented in a timely manner – the goal was to have congestion charging up and running by 2021 – but that has not happened.

The congestion fee had to be approved by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) because some federal roads would be covered by the charge. Trump’s Transportation Department refused to grant permission to create the program, delaying its implementation until President Joe Biden’s inauguration in January 2021.

The federal environmental assessment and public outreach process began in August 2021. In March 2022, the agency requested that the MTA answer 430 questions about the technical aspects of the congestion charge before submitting the plan for a final public review.

Meanwhile, opponents organized to stop the plan. In August 2021, New Jersey representatives Josh Gottheimer, a centrist Democrat, and Jeff Van Drew, a Republican, both hailing from the New York City suburbs, proposed legislation to prohibit the MTA from obtaining federal grants unless New Jersey drivers were exempted from the congestion charges. Congestion pricing supporters countered that New York pays for half of many infrastructure projects connecting the states, such as rail tunnels, that overwhelmingly benefit New Jerseyans, since few New Yorkers commute to New Jersey. Undeterred, Gottheimer partnered with Mike Lawler, a newly elected Republican from New York’s northern suburbs, to introduce another bill to the same effect in 2023.

Nonetheless, the FHWA granted approval in June 2023, citing evidence from other cities that congestion charging has cut air pollution and fossil fuel consumption. London reduced particulate matter and nitrogen oxides by 12 percent and carbon dioxide emissions by 20 percent. Singapore estimates its congestion pricing scheme prevents 175,000 pounds of carbon dioxide emissions per day and Stockholm has seen a 10–14 percent drop in carbon dioxide emissions in its central area.

The MTA’s environmental assessment projects significant benefits from congestion pricing within the core of Manhattan, including more than 11 percent reductions in vehicle miles traveled, carbon emissions, and particulate pollution within the zone. Traffic speeds are expected to improve as a result. But most of the outer boroughs and suburbs will see only very marginal improvements in air pollution (less than one percent drops) and areas such as Staten Island and the Bronx were actually projected to see slight increases in particulate pollution (less than two percent and one percent, respectively), due to increased traffic from cars going around Manhattan to avoid tolls.

Now last-ditch efforts to block implementation have moved to the courts, focusing on the fact that, although congestion pricing will reduce total air pollution, it could increase it in some areas.

After New Jersey governor Phil Murphy failed to persuade the Biden administration to block congestion pricing, he filed a lawsuit arguing that the environmental assessment was insufficient. The mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey, Mark Sokolich, filed a suit in November 2023, claiming his town, adjacent to the George Washington Bridge, which connects New Jersey with a part of Manhattan outside the congestion zone, will suffer from increased traffic. (In April 2024, after this piece was sent off to the printers, the MTA announced it would share revenues with New Jersey.)

The possibility that some low-income areas already burdened by poor air quality may see increased traffic from drivers avoiding the congestion zone, such as parts of the Bronx near the Cross Bronx Expressway, has alarmed even erstwhile congestion pricing supporters such as Representative Ritchie Torres, a Bronx Democrat who represents America’s poorest congressional district.

In December 2023, after months of public hearings, the MTA finally announced the amounts of the tolls: passenger vehicles will pay $15, small trucks $24, large trucks $36, and motorcycles $7.50. Those rates will apply from 5am to 9pm on weekdays and from 9am to 9pm on the weekends. The rest of the time, the costs will be 75 percent lower than the peak time charge. One of the points of congestion pricing, after all, is to incentivize time shifting for trips like deliveries to occur during off-hours. There will be a five-dollar credit for those using an already-tolled entrance for which they are paying an additional separate fee, like the Lincoln Tunnel from New Jersey.

Drivers will only be charged once each day, after which point they can drive around, or in and out of, Manhattan as much as they like, and they won’t be charged for trips originating and ending within the congestion zone – from Tribeca, in Downtown Manhattan, to Hell’s Kitchen, in Midtown Manhattan, for instance. Taxis and ride-hail services will be exempt, but instead they will pay $1.25 and $2.50 surcharges per ride, respectively.

So, is congestion pricing in New York set to happen at last? Will Vickrey’s vision become reality, 70 years on?

‘I’m not breaking out the champagne until the first car gets charged’, former chief engineer Sam Schwartz said. ‘And I’m hoping to be the one driving it.’