Outdated forms of peer review create bottlenecks that slow science. But in a world where research can now circulate rapidly on the Internet, we need to develop new ways to do science in public.

For most of the twentieth century, science looked very different from the way it does today. For one, the internet did not exist. If researchers wanted to share their work with one another, they would meet in person – at conferences and seminars – or circulate their work through print – in letters, books, or journals.

But journals, too, worked very differently. Few studies went through ‘peer review’, the procedure where, after a scientist submits their paper to a journal, the editor sends it out to other scientists, who provide feedback and recommend whether the paper should be published. The practice only became a requirement by most journals in the 1970s and ’80s, decades after World War II.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Before the adoption of peer review, journals focused on quickly disseminating letters and communications between scientists, with little to no editing or external reviewing. In 1953, when Watson and Crick wanted to make their discovery of the structure of DNA known widely as soon as possible, they submitted their paper to Nature particularly because the journal was known for its rapid publication speed.

As you might guess, the absence of peer review also meant there were different standards for journals to decide what to publish. When the editors of journals trusted scientists, they tended to print their studies without question; when they were in doubt, they would send their papers to external reviewers they trusted – but even so, it was primarily the editors who would decide which papers were printed.

The Royal Society was probably the first society to introduce peer review for its journals, although for a long time it was actually a precursor to the kinds of peer review we see today, where papers are sent to scientists who are unaffiliated with the journal.

The Royal Society’s journal Philosophical Transactions had initially been run independently by Henry Oldenburg, the society’s secretary from 1665 until 1677. Oldenburg rarely consulted others about which submissions to publish, and maintained a separation between the journal’s publications and the activities of the society. But few outsiders were aware of this distinction, and in 1751, a botanist named John Hill published critiques and satire blurring the difference between them and ridiculing the quality of research that the journal published, particularly during Oldenburg’s tenure.

In response to the mockery, the society decided that its council would act as reviewers of papers in Transactions, deciding which submissions to publish and which to reject. From 1752, adverts were printed in each edition of the journal, saying that any conclusions or judgments made by scientists in the studies they published were not endorsed by the society. And in the decades and centuries that followed, the society’s approach to reviews developed, with various steps and meanderings along the way. For a short time in the 1830s, reviewers were required to come to a unanimous consensus about which papers to publish, until this turned out to be unworkable. Shortly after, reviewers were expanded to include fellows of the society, not just the council.

Aside from the Royal Society’s journals, others largely began to require peer review in the late twentieth century. This change was not because the concept propagated between journals, but because editors began to receive far more submissions than they could publish. Peer review became a matter of reputation for journals – for example, to avoid accusations of poor curation, as with the Royal Society, or favoritism, as with Nature.

In the 1970s, Nature’s upcoming editor David Davies realized that – contrary to his expectations – the journal had a poor reputation outside Britain. American researchers he spoke to believed it had a British bias: that its reviewers lived in London or Cambridge and had ties to the scientists who sent in submissions. When he enforced peer review as a requirement and recruited new reviewers from other countries, it was to avoid conflicts of interest and establish Nature as a respectable journal worldwide.

One by one, journals adopted peer review as a requirement for scientific research that was to be published.

Journals, which had previously been known for being rapid platforms to circulate research, traded off speed for other functions. They were no longer just disseminators of research, but attempted to back up their reputations by filtering which research was circulated, improving it, and – based on their existing reputations – vouching for its quality.

The operation and funding of journals also changed. While the majority of journals had previously been run by academic societies, many were bought by commercial publishers from the 1960s and onward.

Today, a handful of big publishers – Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor & Francis, and RELX (previously known as Reed-Elsevier) – publish the majority of academic papers across entire disciplines, including the natural sciences, medicine, social sciences, and humanities.

While academic publishing has become a commercial industry, some aspects of journals have remained the same.

Editors of journals still hold a large sway in deciding what gets published, as they can search for ongoing research to solicit and publish and they can reject submissions entirely before sending them out for peer review.

Unlike in book and magazine publishing, scientists who publish in journals remain unpaid by publishers for their work. Instead, academic papers are part of the research output that universities and research funders look at when allocating funding and promotions. On the other side of the equation, journals profit from their reputation – in filtering, improving, and vouching for the quality of papers they publish.

Journals rely on subsidies and subscriptions from institutional libraries, which pay enormous and growing costs to access articles. People outside of large institutions, without library subscriptions, are largely shut out from reading publicly funded academic research as well as reading the comments that reviewers have made on a paper. And despite spending masses of time reviewing articles, scientists who agree to review articles remain, with rare exceptions, unpaid and unrecognized.

Today, researchers contribute masses of their time and effort to reviewing papers that are submitted to journals. It’s estimated that, between them, researchers around the world spent a total of 100 million hours on reviewing papers in just 2020 alone. Around 10 percent of economics researchers spend at least 25 working days a year reviewing them.

Because our systems of scientific publishing have remained in the past – deeply connected to journals – this leads to a growing bottleneck and backlog.

Papers stack up in the email inboxes of editors before they’re shared with just a few handpicked reviewers, who juggle their own research and personal responsibilities with the expectation to review research voluntarily, squeezing it into free time they have.

Reviewers vary widely in the amount of time they can spend reviewing articles, as well as in their specialties, career stages, and the quality of reviews they produce. But journal editors have little idea of how much time they have to spare and can only track their quality on the go, because researchers do review work for many different journals, which work separately. So it’s no surprise that this set-up is a roadblock to publishing and an enormous burden on researchers’ time.

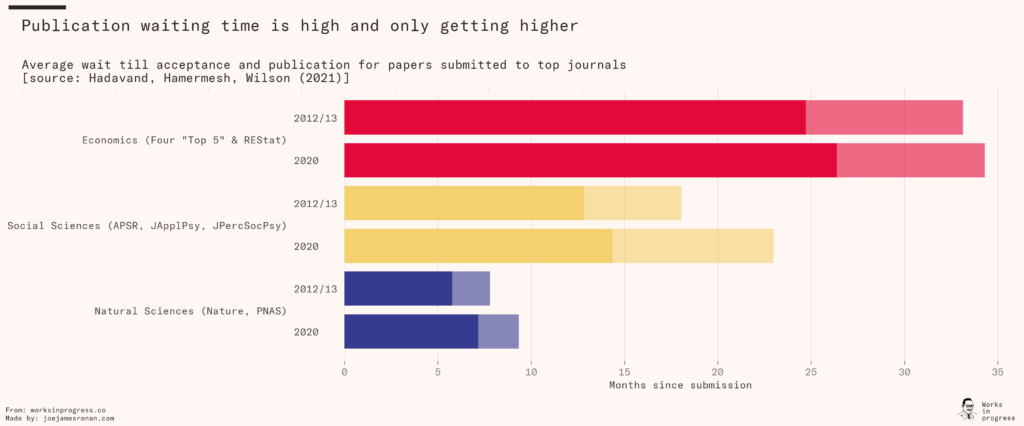

Today, a scientist who submits a study to Nature or PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can expect to be published nine months later, on average. In the top economics journals, the process takes even longer – a staggering 34 months, or almost three years. And the length has been crawling upward each year.

But this is only a part of the problem, because it is only the timeline for papers that are accepted. When researchers have their study rejected for any reason, good or bad, they can send it to other journals instead.

Yet most journals require exclusivity – researchers can only submit one paper to one journal at a time. So, the process that takes months until publishing at the first journal could take years, if the paper was initially rejected, after several rounds of submitting it to different journals. This means that even good papers that are eventually published can be stuck in limbo for years before they eventually see the light of day.

To some degree, these problems can be tackled by journals, by changing the way reviewers are identified and rewarded, and the way articles are submitted.

For example, in some journals, such as the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, and PeerJ, reviewers are given small cash rewards when they submit a review on time.

Researchers have conducted experiments to test these incentives, and have found that they have been effective.

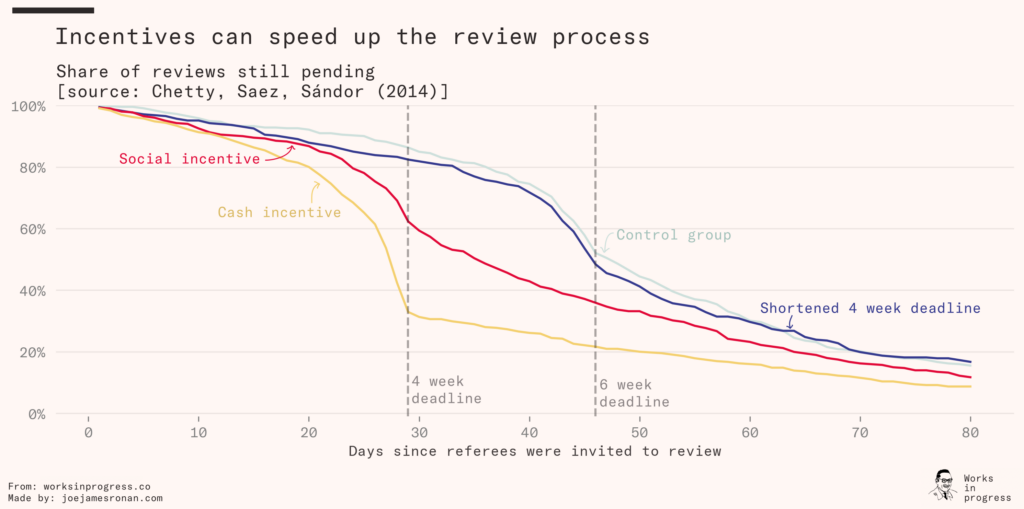

For example, in a large 2014 experiment at the Journal of Public Economics, a team led by the economist Raj Chetty tested four review processes: a control (with a six-week deadline for reviewers to submit their review), a ‘nudge’ of a shortened deadline (four weeks), a $100 cash reward (for submitting within four weeks), and a social incentive (where the times they took to review submissions were posted publicly).

All three of the incentives shortened the time that reviewers took to submit their reviews, with the cash incentive for submitting in a shorter deadline being the most effective. None of the incentives had an impact on measures of quality (the length of review reports or the final decision by the editor to publish the paper), unlike the findings of a previous small-scale experiment.

There are also other approaches journals can use to speed up review without compromising on quality – for example, by using centralized platforms to identify researchers with the time and specialty to review papers.

This is important because a lack of time or expertise are the two biggest reasons that researchers cite for declining to review research and, because journals work separately to find researchers to review papers, the relevant information about reviewers is decentralized.

The website Publons tackles a related problem by letting researchers note down which articles they have already contributed reviews to – but this is different because it keeps retrospective records. Instead, you could imagine a similar platform where journal editors could track the current workload, interests and skills of researchers, to seek out ones with time and relevant expertise to review a paper.

Finally, other types of centralized platforms could be hugely important too. Journals currently have exclusivity agreements (meaning researchers can only submit to one journal at a time) but they also have different formatting requirements, which take a long time to fulfill. By one survey estimate, articles are submitted an average of two times before they are published, and formatting takes up a total of 14 hours per article.

There’s an interesting analogue here in how students submit applications to colleges and universities in different countries. In the US, students tend to make applications to universities in separate groups: the Common Application, the Coalition Application, the University of California application, applications for individual small colleges, military academies, and an assortment of others. Each of these applications has its own guidelines and essay requirements. But in the UK, students tend to make only one through the centralized platform, UCAS, which transfers their personal statements to universities.

On a centralized platform connected to different journals, scientists might be able to submit an article, be matched with reviewers, and select journals where they wanted to have it published – going through the process of submission and reviewing just once rather than over and over again.

But there are two remaining problems with all of these ideas.

The first is that comments and decisions by reviewers can be highly variable even for the same paper.

Reviews vary widely in their quality: In surveys of economics researchers, authors report that around 43 percent of the reviews they receive are high quality, guiding them to improve their analysis, communicate their results better, and put them in context; while 27 percent are reported to be low quality, being rushed, vague, excessively demanding, or even personally insulting.

And reviews also vary widely in their conclusions – how they rate papers and whether they recommend editors to accept or reject the paper.

Most papers are reviewed by one to three people, and agreement between them tends to be low. Papers that receive more disagreement tend to be considered less credible, and it’s estimated that it would take at least four or five reviewers per paper to reach a consistent average rating. But given the delays and lags in reviewing papers, doubling the number of reviewers per paper to achieve this would slow down the process even further.

Agreement between reviewers is even lower in the frontiers of a discipline, where the scientific consensus is less clear. But whether you believe this agreement is good or bad – perhaps because having a more diverse pool of peer reviewers who disagree with one another helps to prevent biases and possibly reconsider the consensus – there’s a problem. With only a few reviewers per paper, reviews are neither a sign of consensus nor intellectual diversity; rather, they are closer to a reflection of chance.

And there is another limit to the effectiveness of efforts made by journals: Peer review is less and less a gatekeeper of which research is shared.

We live in a very different world today than we did when journals were circulated through print: One with the Internet, where data and research don’t need to be circulated in limited and expensive publications. Research can be shared almost immediately with massive networks of scientists through blogs, preprints, data storage platforms and online forums, at little to no cost.

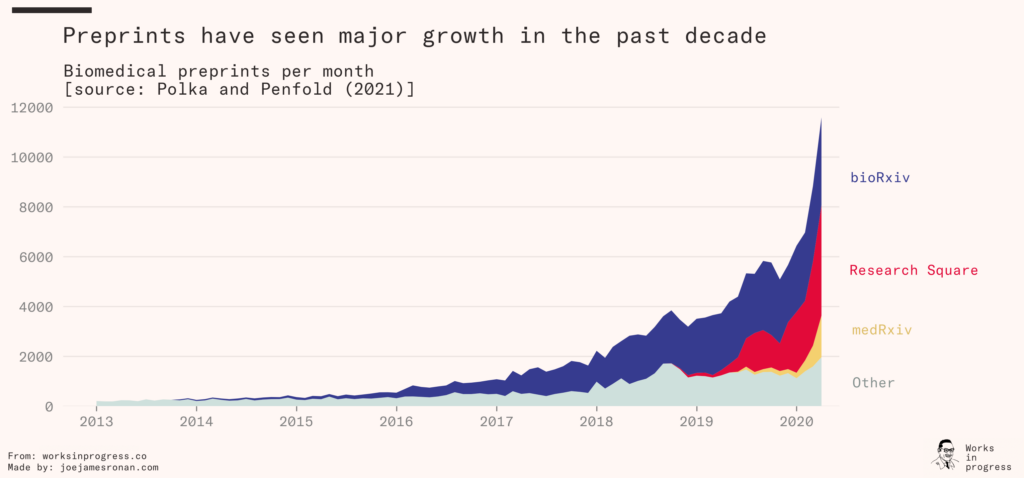

In economics, the circulation of preprints has been normal for decades. In a situation where the average article is published three years after it is submitted to a journal, this is indispensable. But the use of preprints has exploded across many other fields too, and it’s not slowing down.

By 2020, more than 8,000 preprints were being published each month in the field of biomedical sciences alone. These aren’t half-written drafts that go nowhere. The majority of preprints in biology do get published – around three quarters appear in journals within eight months – and by the time they are published, they tend to have just small differences from their initial versions, a finding that persisted during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Research is not the practice of a few researchers working with a few reviewers for months or years before they publish a ‘final product’ of their work – it’s a world where science can be shared immediately, corrected and improved by other scientists in the public eye.

There’s perhaps no better example of this than the way research has been circulated during the Covid-19 pandemic, which has also highlighted other ways to share research and other forms of peer review.

When the first genome sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 was shared in January of 2020, it was shared on virological.org, an online forum used by virologists. Below were publicly visible comments going back and forth between experts, querying and reanalyzing the methods used to sequence those genomes and the potential implications of their findings. The same was true of early sequences from the 2022 international outbreak of monkeypox, where unusual aspects of the genomes were discussed by experts in forum comments, which were visible to the world.

Review work was also indispensable to data on the number of Covid cases, hospitalisations, tests, vaccinations and deaths across the world, which were stored on GitHub. On this platform for sharing code and building software, scores of users from around the world worked behind the scenes and pointed out issues in data collection, definitions, and coding for sources that came from many countries.

Another example is PubPeer, a website launched in 2012 where researchers can create threads to comment on papers that have already been published. Social scientists tend to use the platform to discuss flaws in research methods and the conclusions of papers. However, the majority of comments are made by researchers in the health and life sciences and their comments tend to relate to scientific misconduct – pointing out the manipulation of images in papers, conflicts of interest, plagiarism, and fraud.

The website is especially useful because it collates comments on scientific misconduct from many scientists, and can be searched for comments relating to a particular paper. It has often taken many months or years for journals to correct the record even when papers have had blatant manipulation and flaws.

In 2020, PubPeer was the site where the scientist Elisabeth Bik pointed out various discrepancies and concerns in studies that claimed hydroxychloroquine was a highly effective treatment for Covid-19; the drug was later found to have no benefit against the disease. Bik left academia and worked at a biotech company before she decided to focus on image integrity as a full-time private consultant.

A final example is the use of social media and news reporting during Covid-19. Though social media can amplify misinformation, it’s also been used as a platform to critique poor research methods and comment on published papers. In 2020, when early studies claimed that the infection fatality rate of Covid-19 was under 0.2 percent, epidemiologists and statisticians pointed out flaws and abnormalities in the research on blogs and threads on Twitter, and reporters pointed out conflicts of interest of the authors in the media.

I take several points from these examples.

The first is that not every piece of research needs to fit the format of an academic paper to be useful to the world. Research can be of high quality while being highly incremental, part of a larger series of work, or done with a standardized pipeline (like the sequencing of a genome) that doesn’t require the typical format of ‘abstract – introduction – methods – results – discussion’ used in academic papers.

And reviews don’t just come in a uniform format of comments in text either – they might involve checking the code of an analysis or the images in a paper, reanalyzing the data, or building upon the results, provided the data is made available.

Branching out from this, reviewers don’t need to cover all, or even most, of an academic study for their input to be useful to the wider community. Some people are specialists in particular aspects of reviewing, and comments from different people with different backgrounds – epidemiology, statistics, and even journalism – can focus on different aspects of research and still be valuable, adding to a larger picture. Contrast this with reviews in academic journals, where reviewers are typically expected to comment on the entire paper, regardless of their own domains of expertise, and the absence of comments on sections of a paper can imply that the reviewers believe they are error-free.

What does this mean for the future of peer review?

The future of peer review might mean journals challenging the typical peer review process, and some already do this.

The journal eLife accepts only papers that have previously been published as preprints, and makes the content of their peer reviews public. PeerJ, as mentioned earlier, has rewards for reviewing submissions, as well as public lists of submitted manuscripts that are awaiting review, which other researchers can volunteer to review. It also has a comment overlay on its published papers, where researchers can make public comments on particular paragraphs and figures of a paper that others can respond to.

Other journals have also been experimenting with new models. The journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics uses an interactive peer review platform, where reviewers and the public can comment on submissions during a six-week time window, before authors have to respond to their comments and make adjustments on their papers. The F1000Research journals use a post-publication peer review system, where submissions are immediately shared, before being reviewed by researchers, and then rated by the editor to signify approval.

But I think the future is about thinking much bigger than journals.

Whether we like it or not, research is already, easily and increasingly, published outside of journals, and so are reviews. Reforming peer review, therefore, should mean working with the way science is shared in public, not ignoring it.

Part of this might look like meeting people where they already are. This might involve tools like Altmetrics, to aggregate public comments and critiques of research, so that other researchers and reporters can easily put research into context. Or it might mean centralized review platforms and forums like PubPeer used more widely, to make it easy for people to start threads to comment or critique papers across platforms. Or a wider adoption of tools like Statcheck to detect statistical errors and AI to detect image duplication and manipulation in published research.

But peer review is a continuous process, not different from the way science is created more generally, where research builds on previous work, strengthening or critiquing ideas and theories.

Reviews are a highly valuable type of research output in their own right. They don’t just improve the research that they are directed at, but they put research into context for news reporters, policymakers, the public, and other researchers too. Peer review is not just a practice for journals to try to protect their reputations from criticism. It’s a substantial part of the practice of science; the way we understand research, particularly from fields outside our own expertise.

So the future is not just about using new tools and platforms for peer review; it’s about academia and industry investing in it wholesale by building institutions and teams to produce it and take the process forward.

They can undertake various aspects of this work – whether it’s code reviewing, image sleuthing, Red Teaming, or the many other aspects of review work that are needed today and might be important in the future. And they can learn from practice, so they can continue to create new tools and platforms to automate routine parts of review work to be done better and faster, run experiments to understand which practices work best, and propagate them further.

The possibilities are vast and unpredictable because the ways that we produce science and share it are evolving too. The best tools and incentives to review science are waiting to be discovered, created and adapted – and by investing in new teams and institutions, it’s time to set the scene to build them.