Why are buildings today simple and austere, while buildings of the past were ornate and elaborately ornamented? The answer is not the cost of labor.

One of the unifying features of architectural styles before the twentieth century is the presence of ornament. We speak of architectural elements as ornamental inasmuch as they are shaped by aesthetic considerations rather than structural or functional ones. Pilasters, column capitals, sculptural reliefs, finials, brickwork patterns, and window tracery are straightforward examples. Other elements like columns, cornices, brackets, and pinnacles often do have practical functions, but their form is so heavily determined by aesthetic considerations that it generally makes sense to count them as ornament too.

Ornament is amazingly pervasive across time and space. To the best of my knowledge, every premodern architectural culture normally applied ornament to high-status structures like temples, palaces, and public buildings. Although vernacular buildings like barns and cottages were sometimes unornamented, what is striking is how far down the prestige spectrum ornament reached: our ancestors ornamented bridges, power stations, factories, warehouses, sewage works, fortresses, and office blocks. From Chichen Itza to Bradford, from Kyiv to Lalibela, from Toronto to Tiruvannamalai, ornament was everywhere.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Since the Second World War, this has changed profoundly. For the first time in history, many high-status buildings have little or no ornament. Although a trained eye will recognize more ornamental features in modern architecture than laypeople do, as a broad generalization it is obviously true that we ornament major buildings far less than most architectural cultures did historically. This has been celebrated by some and lamented by others. But it is inarguable that it has greatly changed the face of all modern settlements. To the extent that we care about how our towns and cities look, it is of enormous importance.

The naive explanation for the decline of ornament is that the people commissioning and designing buildings stopped wanting it, influenced by modernist ideas in art and design. In the language of economists, this is a demand-side explanation: it has to do with how buyers and designers want buildings to be. The demand-side explanation comes in many variants and with many different emotional overlays. But some version of it is what most people, both pro-ornament and anti-ornament, naturally assume.

However, there is also a sophisticated explanation. The sophisticated explanation says that ornament declined because of the rising cost of labor. Ornament, it is said, is labor-intensive: it is made up of small, fiddly things that require far more bespoke attention than other architectural elements do. Until the nineteenth century, this was not a problem, because labor was cheap. But in the twentieth century, technology transformed this situation. Technology did not make us worse at, say, hand-carving stone ornament, but it made us much better at other things, including virtually all kinds of manufacturing and many kinds of services. So the opportunity cost of hand-carving ornament rose. This effect was famously described by the economist William J Baumol in the 1960s, and in economics it is known as Baumol’s cost disease.

To put this another way: since the labor of stone carvers was now far more productive if it was redirected to other activities, stone carvers could get higher wages by switching to other occupations, and could only be retained as stone carvers by raising their wages so much that stone carving became prohibitively expensive for most buyers. So although we didn’t get worse at stone carving, that wasn’t enough: we had to get better at it if it was to survive against stiffer competition from other productive activities. And so the labor-intensive ornament-rich styles faded away, to be replaced by sparser modern styles that could easily be produced with the help of modern technology. Styles suited to the age of handicrafts were superseded by the styles suited to the age of the machine. So, at least, goes the story.

This is what economists might call a supply-side explanation: it says that desire for ornament may have remained constant, but that output fell anyway because it became costlier to supply. One of the attractive features of the supply-side explanation is that it makes the stylistic transformation of the twentieth century seem much less mysterious. We do not have to claim that – somehow, astonishingly – a young Swiss trained as a clockmaker and a small group of radical German artists managed to convince every government and every corporation on Earth to adopt a radically novel and often unpopular architectural style through sheer force of ideas. In fact, the theory goes, cultural change was downstream of fairly obvious technical and economic forces. Something more or less like modern architecture was the inevitable result of the development of modern technology.

I like the supply-side theory, and I think it is elegant and clever. But my argument here will be that it is largely wrong. It is just not true that twentieth-century technology made ornament more expensive: in fact, new methods of production made many kinds of ornament much cheaper than they had ever been. Absent changes in demand, technology would have changed the dominant methods and materials for producing ornament, and it would have had some effect on ornament’s design. But it would not have resulted in an overall decline. In fact, it would almost certainly have continued the nineteenth-century tendency toward the democratization of ornament, as it became affordable to a progressively wider market. Like furniture, clothes, pictures, shoes, holidays, carpets, and exotic fruit, ornament would have become abundantly available to ordinary people for the first time in history.

In other words, something like the naive demand-side theory has been true all along: to exaggerate a little, it really did happen that every government and every corporation on Earth was persuaded by the wild architectural theory of a Swiss clockmaker and a clique of German socialists, so that they started wanting something different from what they had wanted in all previous ages. It may well be said that this is mysterious. But the mystery is real, and if we want to understand reality, it is what we must face.

Manufacturing ornament before modernity

The supply-side theory has two parts: a story about how ornament was handcrafted before modernity, and a story about how this wasn’t compatible with rising labor costs. Strikingly, a part of the first story is untrue: far from relying on bespoke artisanal work, many premodern builders used certain kinds of mass production whenever they could. But overall, the supply-side story is still an accurate description of this period: although premodern builders used labor-saving methods where possible, their opportunities for doing so were limited by low populations, low incomes, and poor transport technology, and until modern times, making ornament really was pretty labor-intensive.

There are two main methods of making ornament: carving and casting.

Carving involves removing material until only the desired form remains; casting involves shaping a material into the desired form while it is soft and then hardening it. Not all architectural ornament is produced in these ways (for example, wrought ironwork and ornamental brickwork are not), but a surprisingly high proportion is, so I shall focus on these two methods here.

First, carving. From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, the creation of carved ornament went through several stages in a method called indirect carving. First, a design for the ornament was hand drawn by an architect and modeled in clay by a specialist craftsman called an architectural modeler. Because clay models fall apart when they dry out, it might then be cast in plaster for durability. The design would then be laboriously transferred to a block of stone or wood using something called a pointing machine, a framework of needles calibrated to points on the model so that they show exactly how much of the stone or wood has to be drilled and chiseled away to replicate its form (search YouTube for ‘pointing machine’ to find many videos of these). This carving work was done by hand by a second group of skilled craftsmen. The actual designers would probably never touch either the model or the final product.

Even figure sculpture was produced using a version of this method: the sculptor would model the statue in clay, then craftsmen would transfer the design to stone, often via an intermediate plaster cast. The indirect carving of sculpture dates back to antiquity, and many of the most famous antique statues are Roman copies of Greek originals, including the Apollo Belvedere and the Venus de Medici. Indirect carving faded away in the Middle Ages but was revived in the Renaissance and improved steadily in the following centuries. Initially, indirect carving was used to get the figures roughly right, after which the sculptor would take over to execute the details. But by the later eighteenth century, pointing machines were so good that many sculptors did little work on the actual statue: sculpting was basically an art of modeling in clay, and carving was a sophisticated but largely mechanical process. Canova, Thorvaldsen, and Rodin all worked this way. The stone sculptures that adorn the centers of old European and American cities are mostly stone copies of plaster copies of long-lost clay originals.

Indirect carving enables a limited sort of mass production. It makes it possible to get far more out of one scarce factor of production, namely talented designers. This has some value with figure sculpture: there seem to have been carving factories in the Roman Empire mass-producing copies of the most admired statues. But it really comes into its own with other architectural ornament. The Palace of Westminster is covered with tens of thousands of square meters of extraordinarily ingenious and coherent ornament. This is not because Victorian London was awash with carver-sculptors of genius. It is because virtually every detail of the enormous building, down to the last molding profile, was designed by one man, the strange and brilliant Augustus Pugin. Pugin carved nothing, but he produced an immense flood of drawings, which were executed in stone and wood by numberless other hands. Indirect carving made Pugin many thousands of times more productive than he could have been otherwise.

The prevalence of indirect carving shows that premodern builders were keen to rationalize the production process where possible. But the sketch above also shows how labor-intensive carving remained. Premodern machinery had allowed a tiny number of elite architects to design a relatively huge amount of ornament. But the rest of the carving process was largely manual and bespoke as late as the nineteenth century, using much the same tools as the ancient Greeks, and requiring a huge workforce. Perhaps surprisingly, technology revolutionized the productivity of the creative artist long before it revolutionized any other part of the production chain.

Cast ornament shows the same pattern, with some limited mechanization accompanying persistent labor-intensiveness. Cast ornament is made of materials that are originally soft, or that can be made so temporarily through heating or mixing with water. Up to the nineteenth century, the principal materials for cast ornament were clay and plaster, while bronze was the preferred material for cast sculpture. The process of making cast ornament would begin in the same way as that of carved ornament, with drawings and often models. Molds would then be carved in wood or cast from the models in metal, plaster, or gelatine. The mold would then be used to shape the material. There are various ways of doing this, depending on the casting material and the complexity of the ornament.

Some kinds of mold are destroyed in the casting process, but most are reusable many times. And while some casting materials (e.g., bronze) are expensive, others (e.g., clay and plaster) are cheap once the infrastructure for producing them is in place. So once the initial investment in kilns and molds is made, large quantities of cast ornament can be produced at low marginal cost. This means that mass production of ornament has been theoretically possible since very early times.

Despite this, factory production of ornament did not become general practice until the nineteenth century. The reason for this is presumably that markets were so small that these economies of scale could not be realized. Today, much of the best cast ornament in Britain comes from a factory near Northampton run by a company called Haddonstone, whose products I return to below. Haddonstone has customers dispersed fairly evenly across Britain, and it also exports to Ireland, Continental Europe, the Middle East, and the United States. In a premodern economy, with fantastically high transport costs, its market would have been far smaller, perhaps indeed just the town of Northampton – and because premodern societies were extremely poor, Northampton would have been an even smaller market than it is now. Instead of a potential market of millions of new buildings annually, its potential market could easily have been in single digits. It is highly improbable that the fixed costs of factory production would be worthwhile under these conditions.

The upshot of this is that premodern cast ornament was seldom able to exploit its natural scalability. The cheap cast materials probably always tended to be cheaper than stone carving, but this advantage was not marked, and many premodern societies used carved stone for a wide range of public buildings. In many times and places, wood ornament, which is much easier to carve than stone, was used in common buildings. This suggests it was competitive against plaster and terracotta even at the most budget end of the premodern market for ornament.

In its essentials, the supply-side story is thus true of premodern ornament, even though the romantic idea that every piece of premodern ornament is an original work of art is largely inaccurate. Nearly all premodern ornament was mechanically copied in some way, and some premodern manufacturing methods could in theory have been scaled up to mass production. The claim that modern mechanically produced ornament is distinctively inauthentic or uncreative is highly dubious: mechanical copying has been widespread for many centuries. But premodern copying industries were themselves small-scale and labor intensive, and it is plausible that ornament was only widely used in these societies because labor was so affordable.

Manufacturing ornament in modernity

The supply-side story says that these labor-intensive industries failed to evolve in modernity, and so lost out to competition from industries that did. But the first claim here just isn’t true: in fact, the manufacture of ornament was revolutionized in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Three changes are worth drawing out.

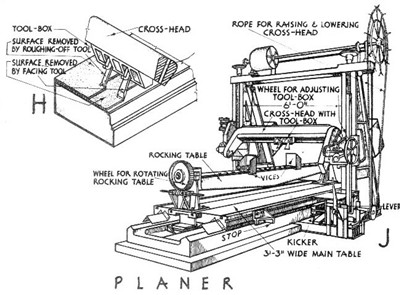

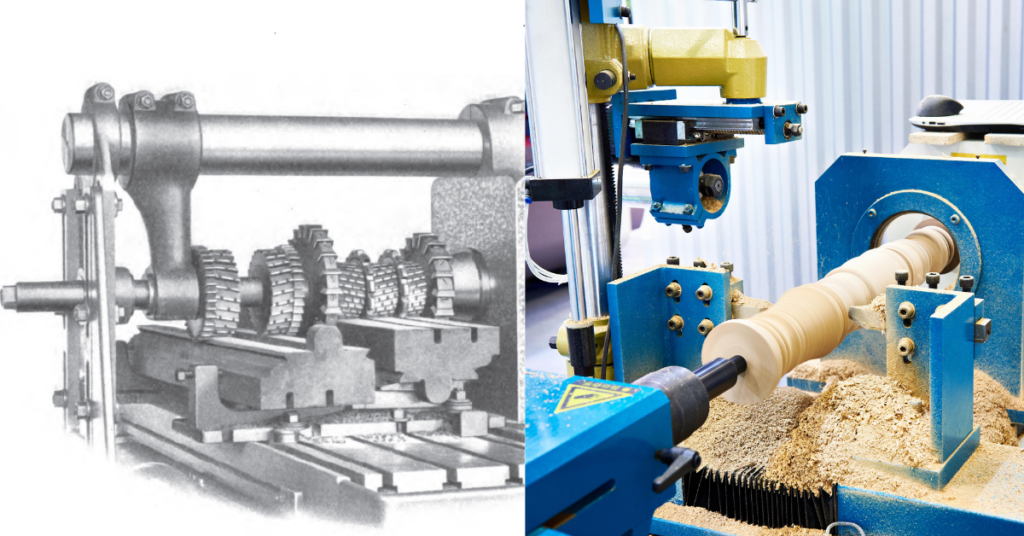

First, inventive toolmakers mechanized the carving process. This is only a qualified truth in the case of stone carving. By the early twentieth century, sophisticated planing machines were capable of cutting simple moldings, column shafts, and so forth with little or no manual finishing work. However, more complex ornaments continued to be carved by hand. A planing machine works by gradually sanding down a block, wearing off material through abrasion until the desired profile is left. This means it is good for producing ornaments that consist essentially of a single profile extended in one dimension. But it cannot easily produce ornaments with undercutting (i.e., drooping projections), and it certainly cannot produce complex multidimensional ornaments like Corinthian capitals or Gothic pinnacles.

In fact, stonework is only finally being mechanized today. I recently visited what is probably the world’s most advanced factory for cutting stonework with a computer-controlled machine, Monumental Labs in New York City. Monumental Labs has constructed a robot that scans a model and then carves it from blocks of stone. The robot works about two to four times faster than a stone carver, and of course it works nonstop, meaning that its overall productivity is 6-12 times greater. It is capable of executing about 95 percent of the carving process, even for figure sculpture, where exact precision is particularly important. Unsurprisingly, Monumental Labs is quickly capturing market share from rivals who still do much of the work with pointing machines and hand carving. Over the next few years, they may succeed in finally mechanizing the process of stone carving. But this is only happening in the 2020s, after natural stone carving has undergone a long decline. So with respect to stonework, the supply-side story may have some validity.

In the case of woodwork, however, mechanization was extraordinarily successful. Two key innovations were steam-powered milling machines and lathes in the nineteenth century. A milling machine has spinning cutters shaped like the negative of the desired profile of the molding. When a beam of wood is passed through it, the cutters remove exactly the correct volume of wood, and an essentially finished ornament emerges on the other side, with many hours of manual carving work completed in seconds. A lathe works on a modification of the same principle: the piece of wood is spun, and the blade is held steady. It is used for things like balusters and columns. Lathes, unlike milling machines, had existed before the Industrial Revolution, but steam made them much more powerful.

In Europe, the effect of these advances was obscured by fire safety laws that tended to ban woodwork on the exterior of urban buildings. But such laws were generally absent in the United States, where there was thus an enormous proliferation of ornamental woodwork in the late nineteenth century, a process bound up with the popularity of what Americans call the ‘Queen Anne’ and Eastlake styles. The ban on exterior woodwork was also lifted in England in the 1890s, resulting in a revival of woodwork decoration that is so characteristic of Edwardian houses, and that makes many Edwardian neighborhoods so much more cheerful than their Victorian predecessors. Although these machines could not generate every kind of woodwork (unlike the astonishing computer-controlled machines, known as CNC machines, that have been developed since), their range was much wider than that of the corresponding machines for stone carving.

The second change revolutionizing ornament manufacture was that scientific advances improved the available materials. Improvements in metallurgy dramatically reduced the cost of cast iron in the early nineteenth century, and its use spread rapidly thereafter. New York City even went through a brief phase of making commercial buildings entirely from iron, many of which survive in SoHo. This proved to have practical problems like overheating, but adding cast iron ornament to masonry buildings became common in many places. Some cities, like Sydney and Melbourne, became especially known for their traditions of cast ironwork.

Another important material is cast stone. Cast stone is a kind of concrete, made by crushing stone, mixing the fragments (called aggregate) with a smaller quantity of cement as a binder, and then casting it in a mold. The crushed stone gives it an appearance resembling natural stone, an effect that is often augmented by mechanically tooling or etching the surface. Good cast stone is remarkably plausible: essentially no layperson would notice that it is not ‘real’, and even a specialist may struggle to tell if it is hoisted 80 feet up a facade. Simple molds are usually machine-carved in wood, and complex three-dimensional ones are themselves cast in gelatine or, today, silicone.

Although there were earlier concretes that bore some resemblance to stone, plausible cast stone seems to have emerged only in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. It became widely used in the United States in the early twentieth century, and many key public buildings in American cities made use of it. Because simple shapes had become easy to carve in stone mechanically, architects sometimes faced the bulk of the facade with natural stone and used cast stone only for the ornament.

While researching this article, I visited the factory of the cast stone manufacturer Haddonstone in Northampton. With the help of the classical architect Hugh Petter, Haddonstone has recently constructed molds based on the designs of the eighteenth-century architect James Gibbs. The molds are filled on a conveyor belt, left to dry overnight, and then opened up in minutes. So it is now possible to buy perfectly proportioned classical ornament, nearly indistinguishable from stone, that has – if the molds and the factory infrastructure are treated as a given – taken only minutes of labor to produce. This sort of capacity is only gradually reemerging, stimulated by the revival of classical architecture, but it was once widespread. Haddonstone is currently manufacturing cast stone ornament for Nansledan, the vernacular-style urban extension to Newquay supported by the King.

The third process was the enormous expansion in the available markets, and the economies of scale that this generated. In the nineteenth century the volume of construction increased tremendously, and transport networks were vastly improved.

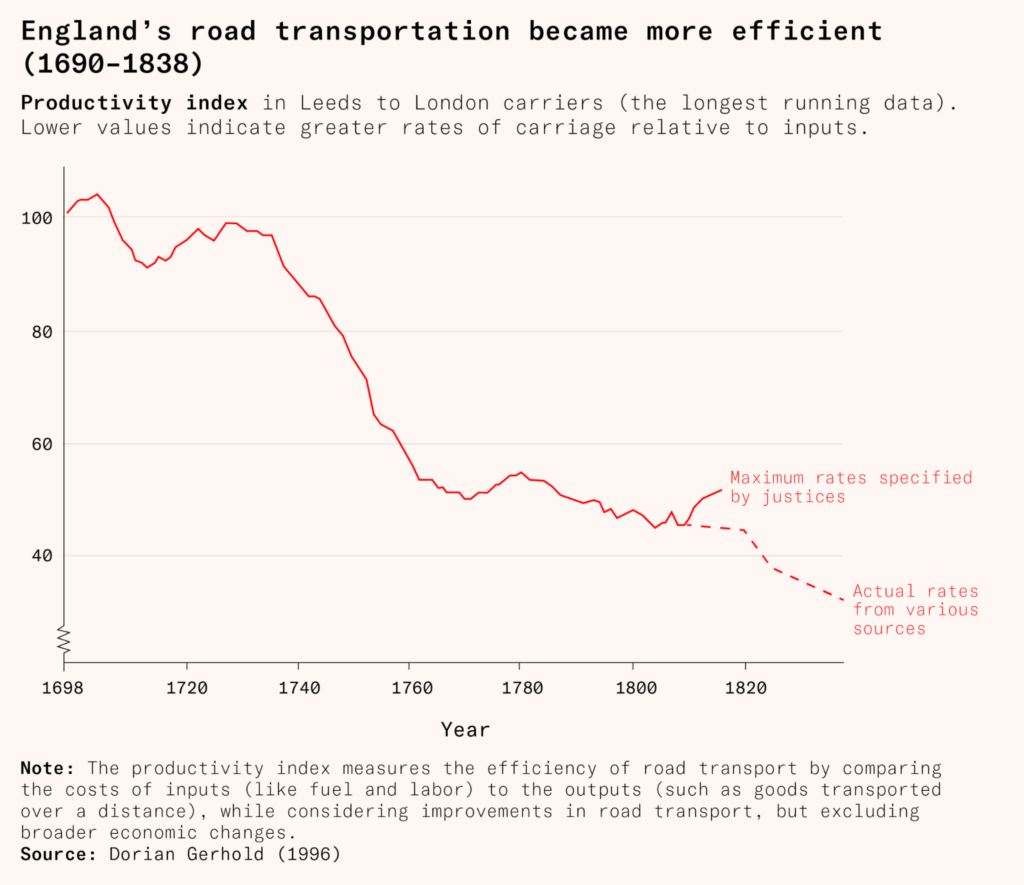

It is well-known that railways cut travel times a great deal, perhaps by four fifths relative to stagecoaches by the late nineteenth century. It is less known that stagecoach speeds themselves had already improved dramatically over the preceding century due to technical improvements and better roads.

In fact, however, these improvements in speed greatly understate the overall improvement in transport. A train is not only faster than a stagecoach: it can carry vastly more stuff, be it freight or people. The key metric here is ‘cost per tonne per mile’. We don’t have perfect data on freight costs, but we can reconstruct a ballpark figure from what we know about passenger fares. A stagecoach fare between London and Brighton, 47 miles as the crow flies, varied between 276 and 144 pence in the early nineteenth century, equating to a per-mile-traveled cost of perhaps 2 pence. By the 1880s, first-class rail travel for such a journey would cost about 0.15 pence per mile traveled. This suggests a fall in overland per-tonne per-mile freight costs in the order of 95 percent, for a service that had also grown five times faster.

Manufacturers naturally took full advantage of this, developing an extensive system of factory production for these methods. For example, the market for architectural terracotta in the United States came to be dominated by just a few huge firms, each of which apparently commanded a near monopoly over thousands of miles. Almost the entire Pacific market was served by a firm called Gladding McBean, whose factory was in Lincoln, California; the Midwest was dominated by a Chicago firm confusingly called the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company; the East Coast was dominated by a New Jersey firm called, more intuitively, the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company. This state of affairs would have been unthinkable just decades earlier, when freight could be carried overland only by carts and pack animals.

A less important but still significant factor was the emergence of extremely large individual buildings. Most early twentieth-century skyscrapers actually had a complete set of ornament modeled for them bespoke, but the buildings were so enormous that substantial economies of scale were still achieved. This is one reason why terracotta was such a popular material for skyscrapers in interwar America, a component of American Art Deco that has now become a striking part of its visual identity.

The democratization of ornament

On the one hand, we have the increasing cost of labor; on the other, we have the fact that less labor was necessary per unit of ornament. Which effect was stronger? For the period from the start of the Industrial Revolution to the First World War, the answer should be obvious to anyone walking the streets of an old European city. The vernacular architecture of the seventeenth or eighteenth century tends to be simple, with complex ornament restricted to the homes of the rich and to public buildings. In the nineteenth-century districts, ornament proliferates: even the tenement blocks of the poor have richly decorated stucco facades.

The revealed evidence is in fact overwhelming that the net effect between, say, 1830 and 1914 was mainly one of greater affordability. To be sure, the ornament of the middle and working classes was of stucco, terracotta, or wood, not stone, and it was cast or milled in stock patterns, not bespoke. These features occasioned much censoriousness and snobbery at the time. But we might also see them as bearing witness to the democratizing power of technology, which brought within reach of the people of Europe forms of beauty that had previously belonged only to those who ruled over them.

What about the period since 1914? Did the economic tide turn against the affordability of ornament? The evidence here is more complex. Over the course of the 1920s and 1930s ornament gradually vanished from the exteriors of many kinds of architecture, though at different rates in different countries and for different types of building. In the decades since, it has seen only limited and evanescent revivals. But we still have good evidence that this change was not really driven by growing unaffordability.

The reason is that there are some relatively budget pockets of the market where ornament has remained pretty common. Virtually any like-for-like comparison of an elite building from 1900 and today will show a huge reduction in ornament. Indefinitely many comparisons are possible, but here is one below, between a British Government office from the Edwardian period and one from the early 2000s.

We could run the same sort of comparison for any two banks, corporate headquarters, parliaments, concert halls, universities, schools, art galleries, or architect-designed houses, and with occasional exceptions we would find the same pattern. But if we try to run it for mass-market housing, we get a more uncertain result. Below are promotional images for mass-market British houses in the 1930s and today. What is striking is how similar they are. Both have carved brackets, molded bargeboards, faux leaded windows, paneled wooden doors, patterned hung tiles, and decorative brickwork. The modern houses have UPVC windows rather than wooden ones, and they are more likely to have garages. Otherwise, they haven’t really changed. The interiors of the modern homes mostly lack the molded cornices of the 1930s ones, but many of them still have molded skirting boards, fielded door panels, and molded door surrounds.

Browsing the website of any major British housebuilder will confirm that, although the quantity of ornament in mass-market housing probably has declined somewhat since the early 1900s, it has declined much less than that of any other build type. This pattern is even more visible in the United States. But this is exactly the opposite of what the supply-side theory would predict.

The supply-side theory says that ornament declined because it became prohibitively expensive, which suggests that it would vanish from budget housing first and gradually fade from elite building types later. In fact, budget housing is almost the only place we find it clinging on.

The obvious explanation is that ornament survives in the mass-market housebuilder market because the people buying new-build homes at this price point are less likely to be influenced by elite fashions than are the committees that commission government buildings or corporate headquarters. The explanation, in other words, is a matter of what people demand, not of what the industry is capable of supplying: ornament survives in the housing of the less affluent because they still want it.

An interesting special case here is the McMansion, the one really profusely ornamented type of housing that still gets built fairly often in some countries. McMansions are built for people who have achieved some level of affluence, but who stubbornly retain a non-elite love of ornamentation. They inspire passionate contempt in many sophisticated critics, to whom they afford a rare opportunity to flex cultural power without looking as though one is being nasty to poor people. McMansions illustrate how easily wealthy people and institutions could ornament their buildings if they wanted to. But, perhaps with that passionate contempt in mind, most of them no longer do.

According to the supply-side theory, the story of ornament in modernity is one of ancient crafts gradually dying out as they became economically obsolete. I have told a different story. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the production of ornament was revolutionized by technological innovation, and the quantity of labor required to produce ornament declined precipitously. Ornament became much more affordable and its use spread across society. An immense and sophisticated industry developed to manufacture, distribute, and install ornament. The great new cities of the nineteenth century were adorned with it. More ornament was produced than ever before.

We can imagine an alternative history in which demand for ornament remained constant across the twentieth century. Ornament would not have remained unchanged in these conditions. Natural stone would probably have continued to decline, although a revival might be underway as robot carving improved. Initially, natural stone would have been replaced by wood, glass, plaster, terracotta, and cast stone. As the century drew on, new materials like fiberglass and precast concrete might also have become important. Stock patterns would be ubiquitous for speculative housing and generic office buildings, but a good deal of bespoke work would still be done for high-end and public buildings. New suburban housing might not look all that different from how it looks today, but city centers would be unrecognizably altered, fantastically decorative places in which the ancient will to ornament was allied to unprecedented technical power.

This was not how it turned out. In the first half of the twentieth century, Western artistic culture was transformed by a complex family of movements that we call modernism, a trend that extends far beyond architecture into the literature of Joyce and Pound, the painting of Picasso and Matisse, and the music of Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Between the 1920s and the 1950s, modernist approaches to architecture were adopted for virtually all public buildings and many private ones. Most architectural modernists mistrusted ornament and largely excluded it from their designs. The immense and sophisticated industries that had served the architectural aspirations of the nineteenth century withered in full flower. The fascinating and mysterious story of how this happened cannot be told here. But it is a story of cultural choice, not of technological destiny. It was within our collective power to choose differently. It still is.