The cities of the developing world could be its growth engine if their streets were not so gridlocked. The solution is laying out wider roads.

Cities enable cooperation. They allow people to specialize, to hire and be hired, to learn from one another, to build things together that none could build alone. Economists refer to the productivity gains that arise from human proximity as agglomeration effects.

The agglomeration effects of cities arise from two things: the physical proximity of buildings to one another, and the intra-city transport system that allows people to move swiftly between them. Buildings without transport are as useless as transport without buildings: the benefits of agglomeration depend on access, on the ability of people and goods to move efficiently across urban space.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

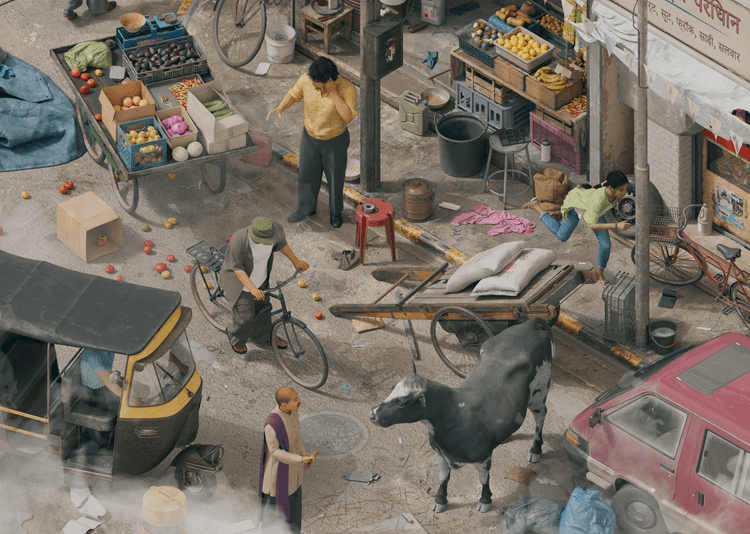

This is where cities in poor countries often falter. As they expand, land is claimed and built upon in small increments, each one rational for the individual settler. These private claims – houses, workshops, stalls – are immediate, tangible, and necessary. But taken together, they crowd out something equally vital: the shared spaces that allow a city to function as a whole. Roads are too narrow, rail lines can’t be laid, and transit corridors are blocked. Commutes stretch and markets fragment, diminishing a city’s economic potential.

In nineteenth-century Europe and America, this tension between private use and public need prompted a historic rebalancing. Railway lines were driven almost to cities’ cores, huge termini were built, and vast fleets of trams rattled up and down wide new public roads built by destroying existing city fabric. A great age of civic architecture dawned, as town halls, museums, courts, parliaments, art galleries, churches and libraries rose up on prime central tracts. These investments were not just luxuries: they were what made industrial-era agglomeration possible.

Today’s rapidly urbanizing cities face a similar moment of decision. Without deliberate efforts to reserve and protect rights of way, they risk becoming collections of poorly connected settlements rather than integrated economic wholes. If they are to deliver on the promises of urbanization, they must make room for the roads, railways, and shared infrastructure that turns density into opportunity.

The public realm in nineteenth-century Europe

Medieval European cities often gave 90 percent or more of their land over to houses, businesses, and shops, leaving little for streets, let alone parks, civic buildings, and public spaces. The same pattern is visible in most Middle Eastern, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese cities. There are occasional striking exceptions, often imperial capitals where the authorities reserved huge spaces for their own purposes. But in most premodern cities, the only public buildings that got much space were churches, mosques, temples and fortifications.

This pattern is still obvious today in those old cities that have remained relatively undisturbed. Examples of this can be found in the historic urban fabric in Cadiz and Kyoto, ancient cities at opposite ends of Eurasia. Both have the narrow streets and densely packed blocks that characterized premodern cities across the continents that lay between them.

Arguably, this distribution of space worked pretty well for premodern cities. They were mostly small, and when people wanted to enjoy green open spaces, they simply walked out into the countryside. Wheeled transport was surprisingly rare until the early modern period, and motorized transport did not exist. It may be that these cities did not need much by way of public space beyond pedestrian alleys, small market squares, and places of common worship.

Whether or not medieval urbanism was right for the Middle Ages, however, it was certainly wrong by the nineteenth century. Many cities became too large for people to reach the countryside on foot, so a need for parks arose. There was a vast increase in wheeled transport, even before the development of cars, for which the unpaved pedestrian alleys of medieval cities were totally inadequate. New kinds of mechanized transport – trams, buses, and railways – arose, all of which required land to be prized out of private hands for public purposes. Public authorities began to provide additional services, from policing to libraries, all of which required civic buildings.

This generated a massive policy response from Western governments. The development of railways and civic buildings are perhaps the most famous element of this, but it is no less true of the road network. In many European cities, arterial streets were cut through the existing urban fabric, demolishing buildings to open up space for traffic circulation. In Paris, a government official called Baron Haussmann created many of Paris’s famous boulevards by destroying close to 20,000 buildings, including his childhood home. Similarly extensive schemes were executed in London, producing Shaftesbury Avenue, Regent Street, Kingsway, and Victoria Street.

These projects were extremely contentious: though owners of expropriated property always received compensation, poorer tenants were often left without adequate substitutes after they were evicted from their homes. Notwithstanding these issues, however, the road cuttings were generally extremely successful in improving urban transport. In the early twentieth century, they were replicated on a huge scale in Japan, when the authorities completely replanned the street network of Tokyo after the 1923 earthquake.

The nineteenth century also reshaped the planning of new urban districts. In most American cities, municipalities compulsorily purchased vast grids of land, reserved the rights of way necessary for a generous road network, and then allowed the city to develop on it. Similar approaches were taken in Spain, Germany, Austria and parts of Italy, although (except in Barcelona) European plans tended to be more complicated than a simple grid. This process was generally less contentious than road cutting in cities, because far fewer people were displaced by it.

In all these urban extensions, the public authorities allocated vastly more land to arterial roads than had been normal in earlier urbanism, or than the private market would have allocated if left to its own devices (unless it had been in unified ownership).

The generous arterial streets of nineteenth-century Europe have paid dividends ever since. Many are wide enough to integrate dedicated lanes for buses, trams and bicycles. In the early twentieth century, many were temporarily dug up and had metro systems laid underneath them. They continue to form the core of urban transport systems today.

Road shortage in the developing world

As noted, the point of cities is agglomeration, the benefits we derive from living in proximity to one another. The agglomeration benefits of cities are enormously varied. City dwellers can join a wider range of subcultures and social groups. They can get to hospital faster in an emergency. They have a wider range of schools, shops, restaurants and theaters within travel distance. People who move to cities report higher incomes, even adjusted for the cost of living, suggesting that demographic differences are not the only reason for higher wages in cities than the countryside.

This agglomeration scales with city size. Not only does moving to any city increase the number of people someone can collaborate with, work for, or employ, but so does moving to a larger city. Agglomeration effects are difficult to measure (as simple regressions don’t distinguish between agglomeration and sorting), but depending on how it is counted, cities seem to exhibit a two to ten percent increase in productivity for every doubling of population.

All these advantages depend upon transport. Cities bring us closer to one another, with all the potential benefits that offers. But how much they do this depends on how good intra-city transport is. In London, a city of almost ten million with an effective transport system, around seventy percent of the population is within one hour’s journey of the city center. In Los Angeles, just four percent of the population can reach the city center within an hour by rapid transit, walking or cycling, but it still manages to be one of the world’s richest cities due to an extensive system of roads. In dense poor country cities, the percentage of people who can reach the city center is far lower, either by active and public transport, or by car.

This problem is only getting worse in poor countries: cities are growing at similar rates to European cities in the nineteenth century, but urbanization is not being paired with similar reforms to urban policy. Instead, development is happening at the expense of public uses of land, actually making cities less efficient over time. This problem shows up most clearly in the differences in land allocated to road networks: 27 percent of Manhattan is dedicated to roads, as is 24 percent of London. These cities are typical for their income group. The North American, European, and Oceanian cities listed in UN-Habitat’s Streets as Public Spaces report have 26 percent of their surface area dedicated to streets.

For the average city in Africa, Asia, or Latin America, only 16 percent is reserved for streets. Just 12 percent of Dhaka, 10 percent of Kolkata, 14 percent of Dakar, 13 percent of Addis Ababa, 12 percent of Nairobi, and 14 percent of Accra are dedicated to roads. Instead, lax building rules have allowed homes and workplaces to take over public spaces.

Urban congestion

The shortage of roads leads to congestion. The IMF estimates average (urban and rural) road speeds in countries like India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Nigeria at less than half of US speeds, and speeds diverge further in cities during rush hour.

Journeys in Delhi are 75 percent longer between 8am and midday and 3.15pm to 6.45pm than during the rest of the day. Knowing what we know from other cities, delays are presumably even more extreme during the peak of the peak, the 8am to 9am and 5pm to 6pm ‘rush hours’. Given that Delhi has the highest land area dedicated to roads of any city in India, and isn’t particularly dense compared to other Indian cities, we should expect to see even higher divergences elsewhere. For example, it typically takes between two and four hours to travel from Mumbai’s central business district in the south to the northernmost residential neighborhoods during rush hour.

As congestion gets worse, even good jobs are not worth traveling to. The direct costs of one-way motorized travel to Lower Parel in Mumbai’s economic center are seven times the hourly wage of the average Mumbaikar, not to mention the opportunity cost of sitting in traffic for hours each day. The city’s overcrowded local trains help solve this problem, but the figures show that the time and monetary cost of road transportation is prohibitive to even the wealthiest residents.

Poorer residents instead make most of their trips on foot, and are thus shut off from the larger labor market entirely. The average amount of traffic slows everyone down. But a commuter who wants to be on time for work can’t expect the average amount of traffic every day – they have to also care about the variability in trip times. In order to avoid being late to work once a week, a person may thus have to show up early most days. While data for this is sparse, one study on three-wheel taxi (a popular and relatively affordable form of transportation) trips in Bardoli, a small city in Gujarat with a population of 476,000, found that 95th percentile travel time was about 40 percent longer than the average.

Interconnected cities and economic growth

By giving land over to public uses, especially infrastructure, including roads, developing countries can improve economic growth, largely through enhancing agglomeration.

One study attempts to quantify the effects directly by looking at satellite images of over 1,000 Sub-Saharan African cities and judging both how many roads they have, and how evenly these roads have been laid out. Both require solving difficult coordination problems but both improve agglomeration for the city at large. The authors find an enormous impact of greater road density: every single kilometer of road per square kilometer of area in the center of a city leads to a city population that is between 1.5 and 7 percent larger 15 years later.

A second study shows that while highway densities and population are often correlated in American cities, once you control for that correlation, highway density is associated with higher returns to agglomeration. American cities at the 25th percentile of highway density – meaning they have fewer highways per square mile than three quarters of American cities – see very little increase in productivity when workers move in, whereas those at the 75th percentile enjoy ‘agglomeration elasticities’ of 0.04. In practical terms, when both cities double their population, the ones with dense highways see output per worker climb roughly four percent; the other sees no productivity change.

In India, state governments that are politically aligned with the national government enjoy more road building for economically arbitrary reasons. Manufacturers in areas that benefited from such fiscal largesse grew total factor productivity at a rate of a quarter of a percent for each one percent increase in road density. Similarly, in China, the investment to build the 98,000 kilometers of motorway added between 1990 and 2012 had an annual return of 11 percent due to productivity gains.

Some studies exploit semi-random assignment of infrastructure investment to show that road building also has an impact on property values. Many Mexican slums have unpaved roads, such that while rights of way exist, using them is slow or impossible. The Mexican city Veracruz decided to pave as many of these roads as it could afford, but was unable to afford every one of the projects it thought valuable. It decided to randomize the choice so that its public works program could be independently evaluated. Directly affected properties, those on the roads that were paved, saw their value increase, such that the investment would have returned two percent after the cost of the paving. These households increased their motorized vehicle ownership by half, and were much more likely to use them to get to work. But properties all around the paved roads increased in value too. Once all of these spillovers were accounted for, the investments returned 55 percent. A separate study found similar results for Kampala in Uganda.

In response, developing world cities are starting to use extension plans, as in nineteenth-century Europe. Abuja in Nigeria, Putrajaya in Malaysia and New Cairo in Egypt are examples. Some have even cut Haussmannesque boulevards through unplanned older areas, like many Iranian cities under the Pahlavis.

Rights of way as an investment in the future

Generous road allocations early on are especially important because poor road allocations can be incredibly sticky. A full 88 percent of named roads in large American cities in 1840 were still in existence in 2011. Mistakes made early on in the life of a city can very easily become permanent. As cities mature and are thus increasingly constrained by their road allocations, they face a series of bad options. They can build within very limiting constraints, risk the political and humanitarian risks of bulldozing through those constraints, or pay the price of building around them.

European governments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries occasionally ate the political cost of bulldozing through constraints, like the Haussmann cuttings discussed above. But doing so required vast numbers of people to be expelled from their homes, at massive cost and controversy, and twentieth-century attempts to do it, like London’s abortive Ringways project, generally failed. Today, even digging up roads to put underground railways under them is so controversial in both developed and developing countries that it rarely happens.

This is why setting aside a generous endowment of road space is one of the most valuable bequests that city builders can make to future generations. This endowment may initially be excessive, and used somewhat inefficiently. The arterial roads that European cities built in the nineteenth century often had very light traffic initially. But bequeathing rights of way pays an extraordinarily good dividend.

Western cities that failed to set aside wide rights of way in the nineteenth century greatly constrained their options later on. For example, London would benefit greatly from restoring the tram network it enjoyed before the 1950s, but most arterials in London (a largely unplanned city) are only two lanes wide, so dedicated tram lanes would mean complete closure for all other traffic. Many European cities would also benefit from four-tracked subways, allowing for express trains like New York, but their roads are generally too narrow to fit more than one track each way under them.

A generous endowment of road space doesn’t mean domination of the private car. Road space is necessary for cycle lanes, bus lanes and tram lanes. The boulevards of Continental Europe were busy with trams, buses and cyclists before cars were even invented. New York City’s four-track subway lines, which allow a mixture of expresses and stopping trains, could not have been built below narrower European streets. Bogota’s Bus Rapid Transit system, which accommodates 40,000 riders per lane-hour, requires four lanes and runs on a 70-foot-wide strip of road. Bogota’s BRT supports much higher throughput than other systems because the outer lanes allow moving buses to pass those stopped at stations, thus preventing ‘bunching’.

By contrast, Dhaka’s less than 20-feet-wide streets barely have space for two buses to pass, and even its biggest infrastructure projects often offer narrower egress than Bogota’s requires. Dedicated bus space is still road space – and it’s easier to dedicate bus space if there is more road space to begin with.

Rail, too, can be built more cheaply if a city has already reserved the right-of-way early on. An older analysis of Western metros found that elevated rail cost at least twice as much per kilometer as at-grade rail, and underground systems cost four to six times as much. Even underground rail is cheaper if it is cut and covered under wide arterial roads, like the New York Subway, rather than bored deep beneath the surface. Provided cities reserve rights of way when neighborhoods are laid out, they can defer the capital costs of rail to a point in time when they would presumably have a much larger tax (and customer) base.

The urban population in Africa in particular is expected to double in the next 25 years, and the geographical footprint of African cities will likely increase by much more as Africans become richer and build larger homes. Asian and Latin American cities will also grow swiftly, though not quite at these rates. As vast swaths of rural land transform into cities, Asians, Africans and Latin Americans have the opportunity to build these cities from the ground up, expanding the amount of space allocated to roads on the periphery of cities as they expand and bypassing expensive fixes down the line. This would be in exact parallel to the city plans of the Victorian West, which largely accepted an inefficient maze as the old core, but planned for generous wide streets across the rest of town – streets they later turned into tram or busways, or dug up to build cut and cover railways.

This does not mean emulating the car-dominated urbanism of the postwar United States. In fact, the most walkable Western cities are those with the highest road allocations, generally making use of the opportunities for segregated cycling, bus and tram lanes that road space creates. Developing world cities could unite superb systems of circulation with beautiful and walkable urbanism.

To some extent, Manhattan exemplifies the development pattern we discuss here. In 1811, NYC commissioners revealed the plan to create a uniform grid on the island of Manhattan, stretching up beyond the small then-occupied area of lower Manhattan. This was done at a time when the population of Manhattan was roughly 100,000, and when the real per-capita GDP of Western Europe and the Anglosphere was lower than it is now in Sub-Saharan Africa. It was a time when literacy in the US was roughly the same as it is in India now, life expectancy was lower than that of any country today, and when the density of horses in New York City precipitated a manure and carcass crisis. Cities in the developing world can manage this level of planning today. In fact, they could do better, especially since Manhattan has failed to take full advantage of the opportunities for cycling and public transport that its built density and high road share create.

Growing cities in poor countries can set themselves up for success, emulating and surpassing the success of European and North American planners in the nineteenth century. At the low cost of reserving future rights of way, planners in developing have an opportunity to ensure now that people in these countries move as fast as people in the West, access labor markets as easily, and live in an urban form more reminiscent of the boulevards of Paris than the gridlock and dark underpasses of Mumbai.