The first vaccine was a lucky accident. Now we can design new vaccines in weeks, atom by atom.

In 1796, when Edward Jenner developed the first vaccine, against the smallpox virus, no one knew what viruses were, let alone connected them to diseases.

Many believed Jenner’s vaccine worked because it depleted the body of the specific nutrients the disease needed to thrive. In reality, his concept worked because of the good fortune that cowpox infections provided cross protection against smallpox. It would take almost a century to work out how to develop vaccines against other diseases.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

Stocks of Jenner’s vaccine would die out repeatedly, and needed to be rederived from scratch many times. Keeping a vaccine alive in the nineteenth century was grueling, requiring arm to arm chains of transmission just to preserve the material.

The process improved slowly. In the 1840s, doctors invented a method to grow the smallpox vaccine virus more safely and reliably on the skin of calves. The 1890s saw a method to keep it from spoiling quickly by mixing it with glycerin, and in the 1940s, scientists learned how to freeze-dry it to survive heat and long journeys. In the 1960s, the bifurcated needle, with a forked tip that could hold a tiny drop of vaccine, made it possible to use only a quarter of the usual dose and helped scale up vaccination. Technological innovations like these made it possible to eradicate smallpox worldwide.

Jenner’s discovery in the eighteenth century transformed the world. But it also reflected the primitive knowledge and technology of the time. It would take another 90 years for scientists to formulate germ theory. Another half century would pass before Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll invented the electron microscope, allowing scientists to see the virus that caused smallpox for the first time.

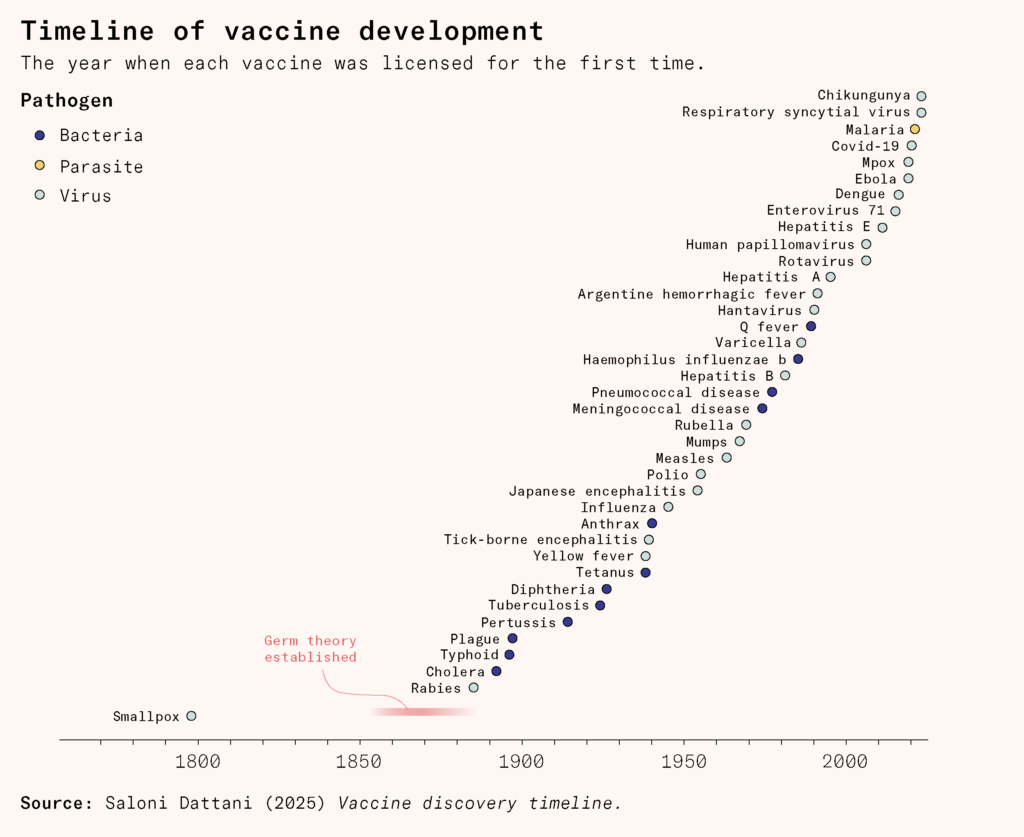

Two hundred years ago, vaccines were serendipitous; today, they are designed. We can now visualize the structure of pathogens at an atomic level. We can purify and design ingredients, boost our immune response with adjuvants, deliver vaccines in safer packages, and manufacture them in billions of doses. We can track pathogens’ evolution in real time and adapt vaccines to new strains.

It has never been easier to develop new vaccines. We are living through a golden age of vaccine development. The future holds even greater breakthroughs, but only if we continue to invest in them.

Pasteur and the culture of vaccinology

The smallpox vaccine was serendipitous. It just happened to be the case that a related virus, cowpox, could protect against smallpox and that cowpox was mild enough to be used safely.

Ninety years after Jenner, Louis Pasteur worked out how to replicate his success for other diseases. Pasteur was already famous for his fermentation techniques and developing the process now called pasteurization.

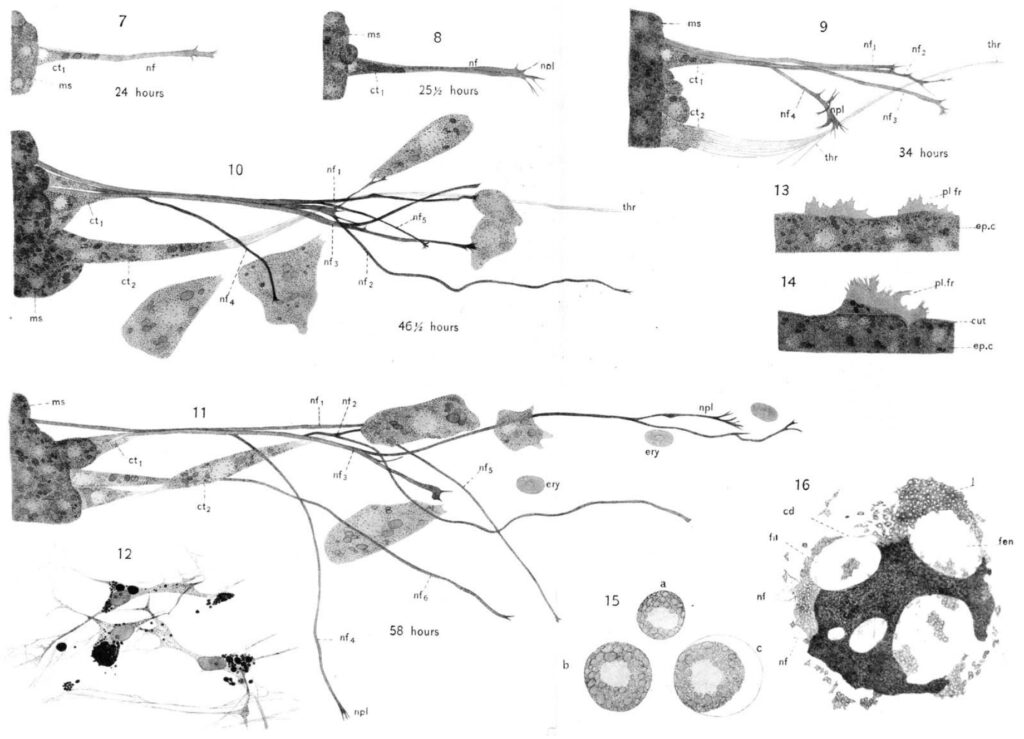

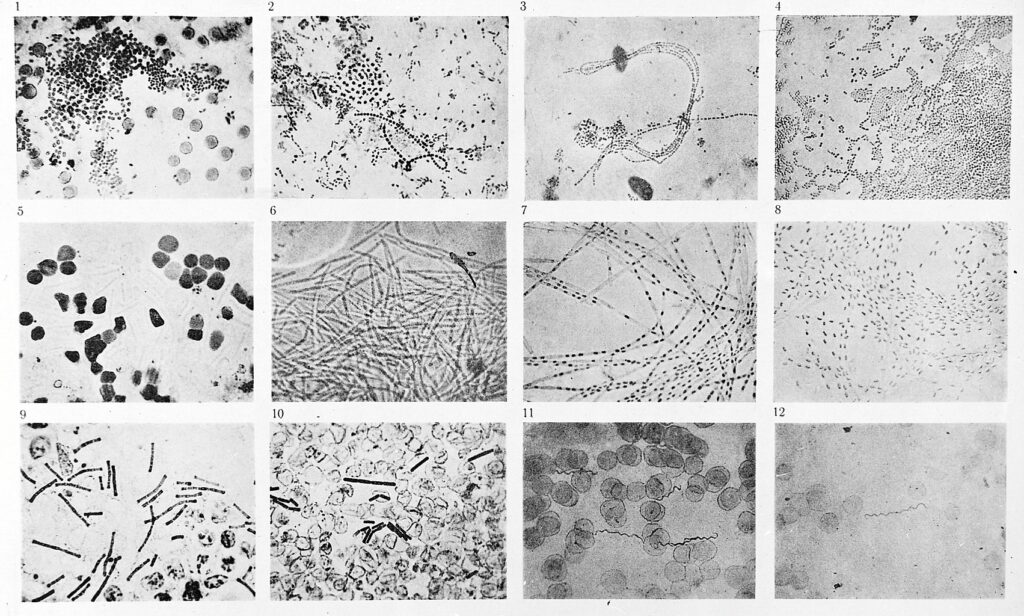

In the 1870s, he began to study infections in farm animals, starting with chicken cholera. He grew the bacteria in the lab and kept them alive via ‘serial passage’, transferring them to fresh broth every few days, and injecting them into chickens to study the disease. Fresh cultures were lethal: nearly all the chickens died within days.

During the summer of 1879, while Pasteur was away, his assistant Émile Roux continued the work. Roux tried reculturing flasks that had stood for weeks, but the broth had soured, and the bacteria grew poorly. He then injected it into chickens and noted that some survived. Perhaps the bacteria had become too weak to cause disease? But surprisingly, when he injected the same chickens with a fresh, deadly strain, some survived; it had somehow protected them. When Pasteur returned, they continued experimenting, gradually learning that acidity and prolonged exposure to air could weaken the microbe and protect the chickens. With this, they developed the world’s second vaccine.

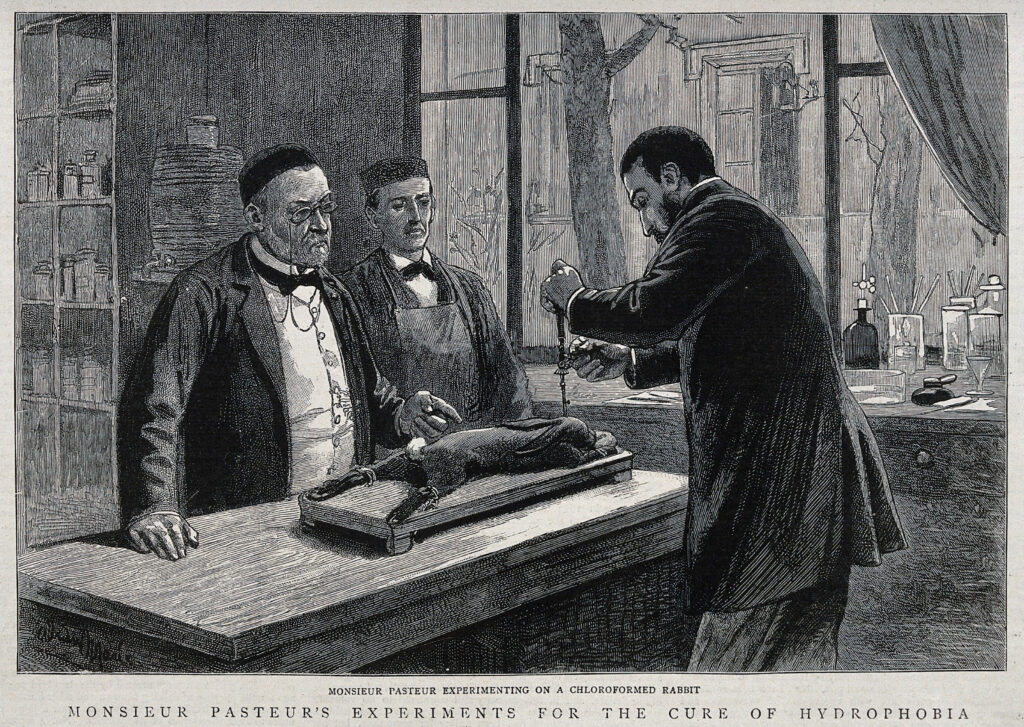

Then they developed another, against animal anthrax, this time inactivating the bacteria with chemicals, before turning to one of the deadliest diseases: rabies. Almost everyone who developed symptoms from a rabid animal’s bite died within weeks, but its microbial cause was unclear. The rabies virus, like other viruses, was too small to be seen under microscopes of the time. But Pasteur and Roux reliably found that brain tissue from a rabid animal could cause rabies in another animal.

After hundreds of experiments, they finally developed a vaccine. Roux extracted brain tissue from a rabid dog and injected it into the brains of rabbits after drilling a small hole into their skulls. He then passaged the material from rabbit to rabbit this way, eventually going through 90 rabbits in a row. Finally, he dried the tissues in closed flasks to weaken the pathogen and injected the material into dogs, gradually exposing them to higher and higher doses, helping them build up protection.

As the animal experiments seemed successful, Pasteur and Roux moved to treat people who had been bitten by rabid animals, helping their bodies build up antibodies before the disease could fully take hold. In 1885, they treated two young boys bitten by rabid dogs and saw their first indications that the procedure worked. One of the deadliest diseases had become preventable. Rabies would eventually be eliminated in many countries with vaccines built on their idea.

Their methods could be used to develop vaccines systematically. One way was to force a pathogen into a different environment until it lost its virulence (‘attenuation’); another was to use heat or chemicals to inactivate the pathogen (‘inactivation’). Both prevented pathogens from causing disease in humans while preserving their structure, so the immune system could recognize a similar pathogen in the event of future exposure.

But protecting large populations was still a distant prospect. Pasteur developed vaccines by culturing microbes in whole animals, which was inefficient and carried contamination risks. It was essential to find a way to cultivate cells – not entire tissues or animals – in a lab.

Robert Koch, a bacteriologist and Pasteur’s rival, would make a major advance. While Pasteur fermented microbes in liquid broth, Koch wanted to cultivate bacteria on solid media to see them under the microscope. His solution was to solidify nutrient broth in a dish with gelatin and cover it with a bell jar. The gelatin was later replaced by agar (a jelly-like material derived from seaweed) and the bell jar was replaced with an additional lidded dish in an invention by his assistant Julius Petri, creating what is now known as the ‘Petri dish’. Paired with Pasteur’s methods, tools like these helped support a wave of research and the development of new bacterial vaccines.

But scientists still couldn’t cultivate animal cells. They clumped together on a plate, ran out of nutrients, and quickly died. And as viruses are obligate parasites, requiring living cells to replicate, they couldnʼt be cultivated this way at all.

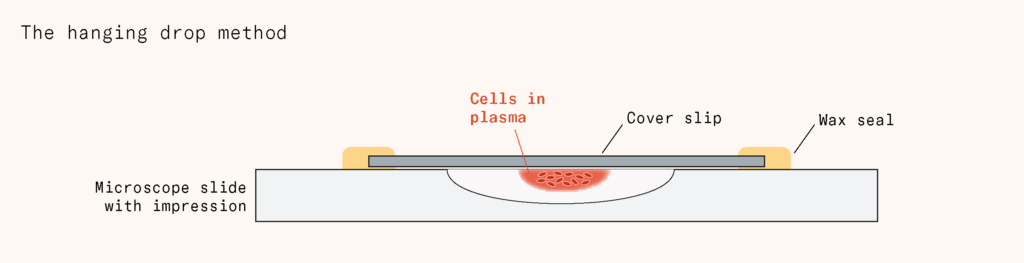

The next step forward came from neuroscientist Ross Harrison in 1907, who developed the hanging drop method. He took a piece of spinal cord from a frog embryo and put it in a drop of its plasma, placed it on a thin glass coverslip, inverted it over a concave slide, and sealed it with wax – creating a drop that hung suspended and stayed moist and rounded while the plasma provided nutrients and structure. The nerve fibers stayed alive, growing for weeks.

By the 1920s, scientists were isolating cells from tissue, watching them migrate across glass surfaces and, once they had used up the nutrients on a plate, cutting the growing regions and transferring them onto a new plate, creating longer lineages of cells. Such methods helped develop vaccines against diseases like polio as scientists figured out how to propagate poliovirus in cells outside the nervous system.

Additional technologies made the process safer: antibiotics reduced bacterial contamination, and autoclaves sterilized instruments with high-pressure steam. Later, cryopreservation helped freeze cells for long term storage, and animal broths were replaced with simpler preparations like Harry Eagle’s medium, which contained only glucose, amino acids, salts, and vitamins.

Researchers also developed machinery to grow cells. For cells that typically grew suspended in liquid, there were stirred-tank bioreactors, which bubble in oxygen and stir the solution to distribute nutrients. For those that still required a surface, there were microcarriers, with tiny beads suspended in liquid, and the roller bottle system, where glass bottles rotate slowly to increase cells’ surface area while keeping them evenly bathed.

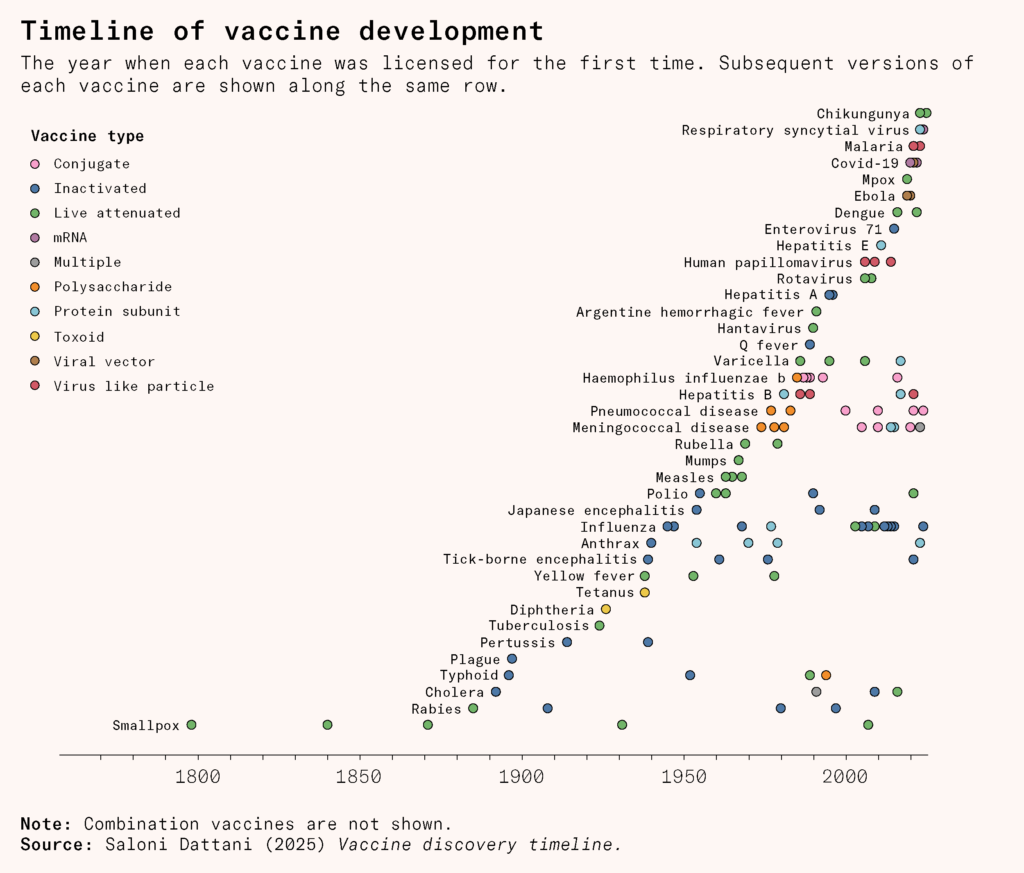

Vaccinology had become a systematic science, based ultimately on the foundations laid by Pasteur. By the mid-twentieth century, scientists were producing vaccines against typhoid fever, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, influenza, polio, yellow fever, and other diseases.

The microscope revolution

What was remarkable about Pasteur’s approach was that he developed some vaccines without ever observing the pathogens, through empirical testing alone.

It wasn’t strictly necessary to see pathogens to develop vaccines for them, but observation made others possible. Take tuberculosis, whose symptoms are easy to confuse with other diseases. The bacteria that cause it were eventually identified through microscopy. Without such careful examination, it would have been difficult to cultivate the right bacteria and remove other contaminating microbes from a vaccine preparation.

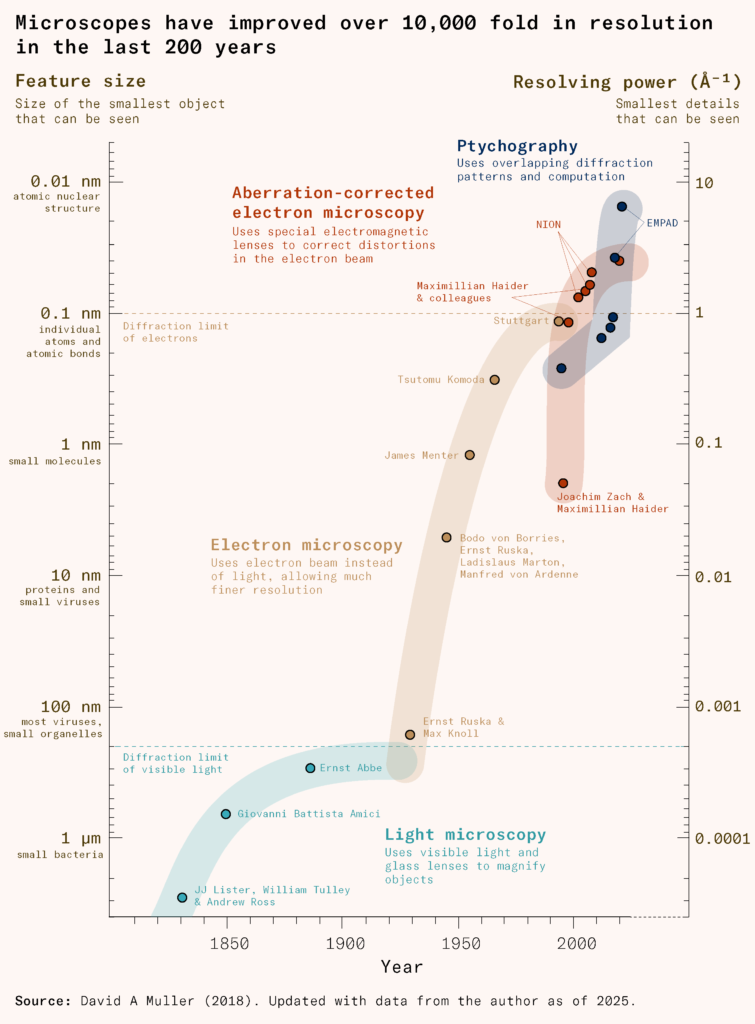

Fortunately, microscopes had been undergoing a revolution of their own. Over two hundred years, their resolution would improve more than ten thousandfold, allowing scientists to examine not only cells, but bacteria, then viruses, their protein structure, and, eventually, the individual atoms that comprised them.

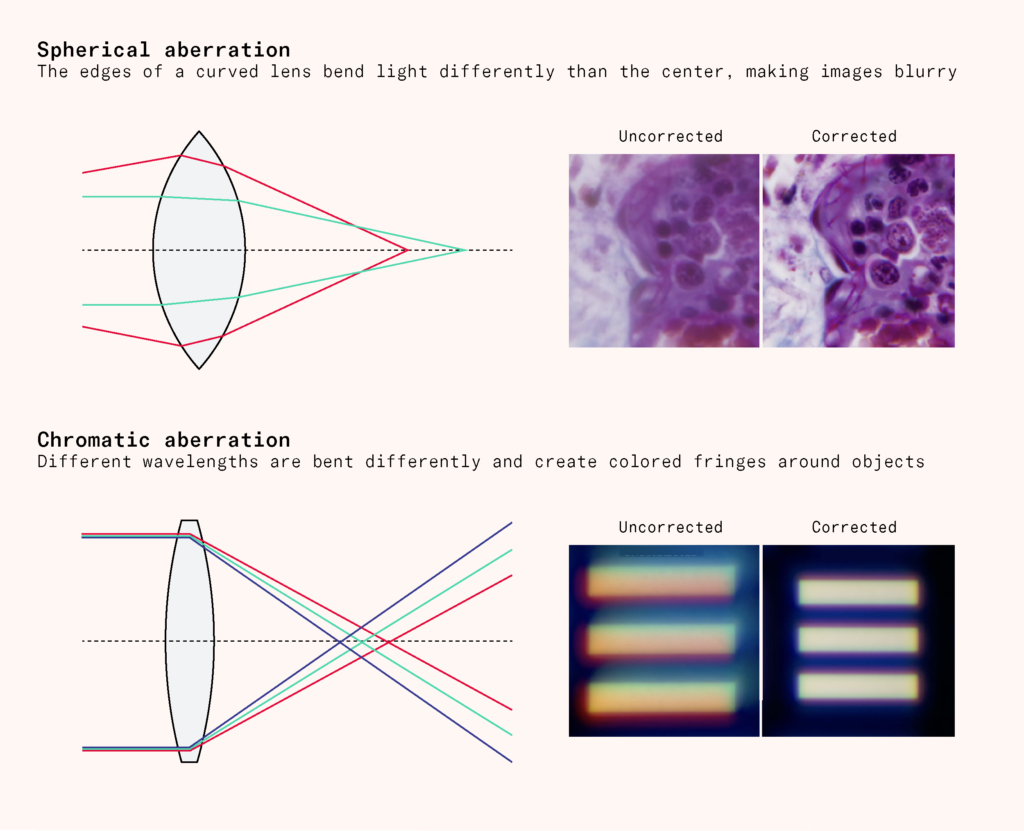

In 1800, the French anatomist Xavier Bichat had classified the body into groups of similar cells, like muscle or connective tissue, using only a hand lens. Bichat distrusted nineteenth century compound microscopes, probably for good reason. Many apparent discoveries of the time were actually caused by optical problems like spherical aberration, where the edges of a curved lens bent light differently than the center and made images blurry, or chromatic aberration, where different wavelengths were bent differently and created colored fringes around objects. What looked like a cellular feature might simply be a distorted lens.

Various innovations were needed to make microscopes more precise. One step came in 1830 from the wine merchant JJ Lister, who studied lens making as a hobby. By varying the distance between lenses, he worked out how to develop achromatic and aplanatic lenses, which reduced color and spherical aberrations, respectively.

Improvements continued, along with new techniques to view more biological material for longer and with greater detail. Scientists developed better fixatives to stabilize cells and prevent them from decaying, staining dyes that bind to molecules to reveal structures like the cell nucleus, and sectioning equipment, which cut tissue into thin slices to allow light through.

As the nineteenth century progressed, scientists began to see cells’ organelles and observe cell division. They increasingly recognized cells as the units that all living organisms are made of. And with improvements in culture methods, they observed microorganisms – bacteria, fungi, and parasites – infecting cells and causing disease.

Most famous was the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, discovered by Robert Koch in 1882, at a time when tuberculosis was killing thousands each year in growing cities like Berlin. Before Koch, researchers had managed to reproduce tuberculosis in rabbits by injecting them with phlegm from infected patients, but struggled to identify its microbial cause. Although they didn’t know it, the bacteria’s waxy cell walls, rich in mycolic acids, repelled water-based dyes, making the bacteria difficult to stain.

Visualizing them would take ingenuity. Taking lung tissue from an autopsy, Koch applied standard dyes and then added ammonia, making the solution more alkaline. It made it possible for the dyes to attach to the bacteria, and as the dyes latched on, they revealed, at last, the pathogen responsible for one of humanity’s greatest killers.

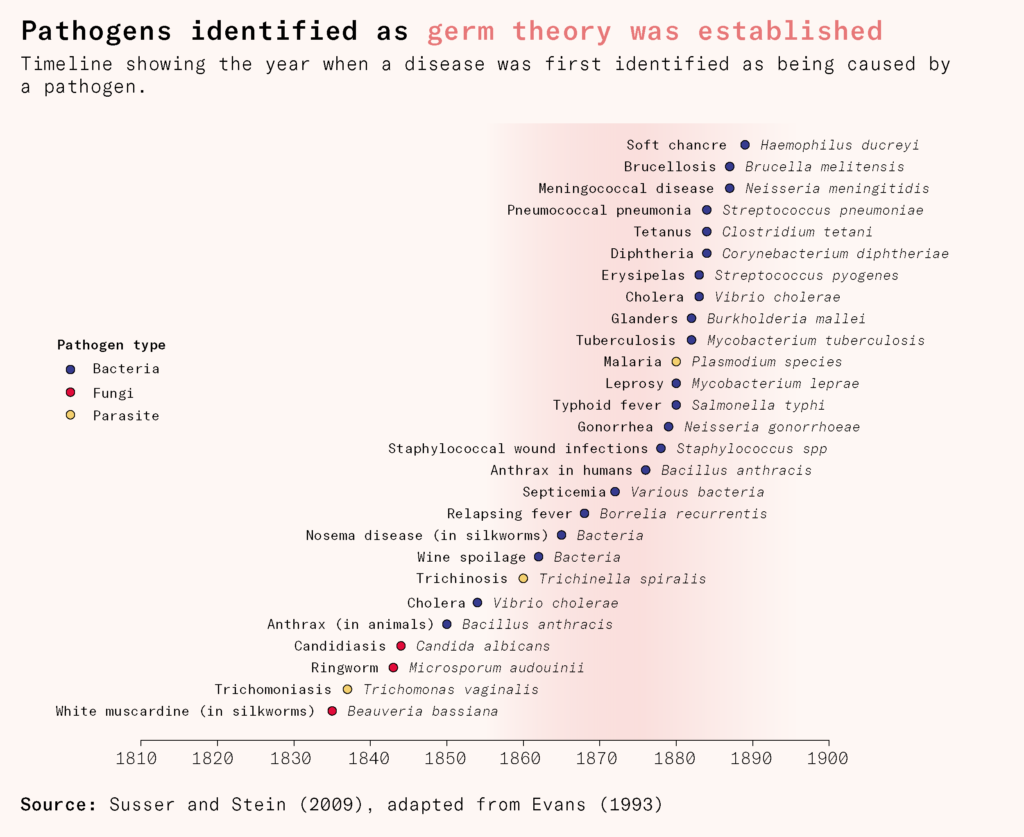

His discovery was part of a surge of research in microbiology in the late nineteenth century, now known as the golden age of microbiology. One by one, long standing mysteries of diseases – tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid, anthrax, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, meningococcal and pneumococcal disease – were being resolved.

No viruses had yet been observed: they were still invisible under the microscope, being much smaller than bacteria. Unfortunately, by the end of the nineteenth century, improvements in microscopy were reaching a hard limit.

The physicist and businessman Ernst Abbe had formulated an equation that would explain why. He found that a microscope’s optical resolution depended on the wavelength of light and the numerical aperture of the lens (a measure of its ability to gather light). Light microscopes couldn’t focus at high magnification because, no matter how clear the lenses were, they couldn’t distinguish details closer than about half the wavelength of visible light, roughly two hundred nanometers. When two points were closer together, light waves directed at them would interfere, blurring them into a single spot.

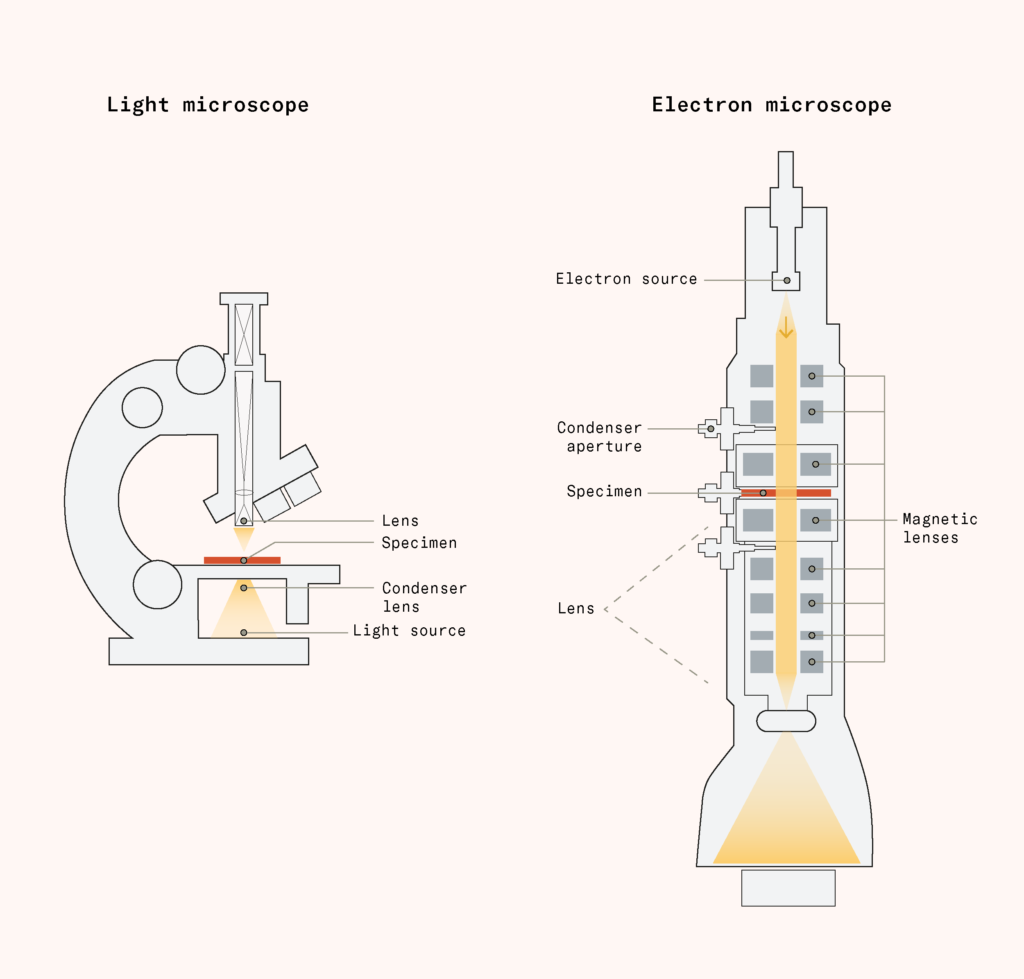

It would take until the 1930s for physicists Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll to invent the electron microscope, replacing light with electrons, which have a smaller wavelength, and extend this limit. Their invention required various advances: discovering the electron, inventing magnetic lenses, and improving vacuum technology.

Electron microscopy combined them all. Electrons can’t be bent by glass the way light can, so electron microscopes instead use magnetic lenses: coils of wire carrying current that bend and focus the electron beam. To keep the electrons from scattering off, the instrument operates in a vacuum. The pieces work in stages: a source produces the electron beam; a condenser aperture shapes it; magnetic lenses focus it progressively onto a specimen; and more lenses project and magnify the image onto a detector.

The first electron microscopes were fragile prototypes. Improving the vacuum seal, brightening the beam, sharpening the lenses, and using better cameras led to an enormous payoff: magnification thousands of times greater than light microscopy.

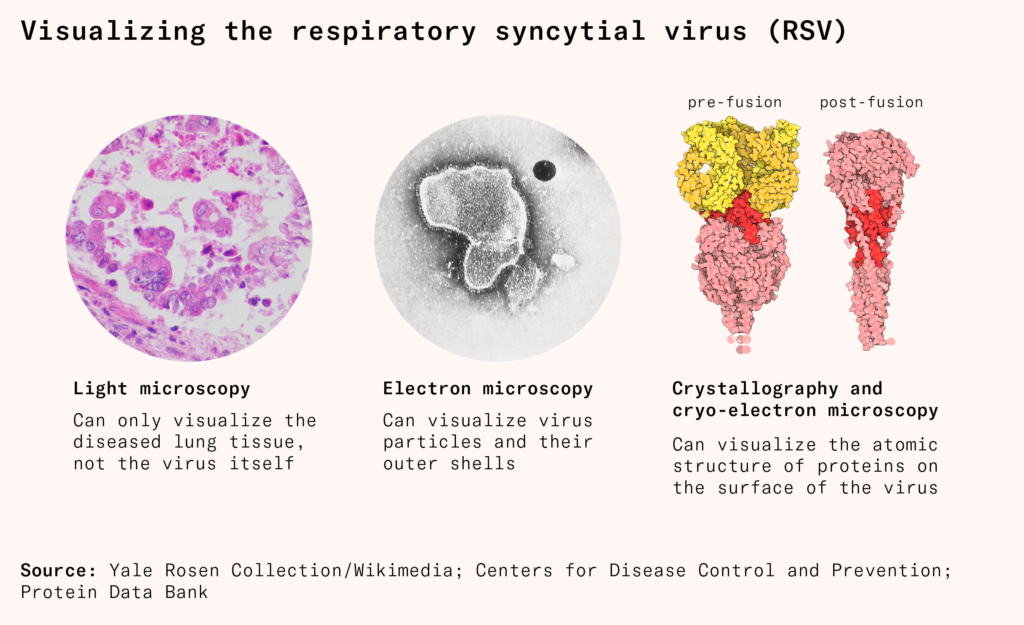

Electron microscopy gave microbiologists their first direct look at viruses, finally revealing their geometry. But the electron beam could collapse biological material like proteins and membranes, leaving mere outlines and shadows. It would take until the 1980s for scientists to see the precise internal structure of viruses, with the invention of cryo-electron microscopy. Here, a thin film of the sample would be plunged into a very cold liquid so fast that water solidified without forming ice crystals. This glass-like water, called vitreous ice, locked molecules in place in their native structure.

With time, scientists developed better detectors and computational methods to combine overlaps from thousands of images to reconstruct the 3D structure of microbes down to their individual atoms.

Take respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. In the last decade, visualizing the atomic structure of its proteins helped finally develop safe and effective vaccines, decades after previous efforts failed. The critical site was a protein on its surface, the fusion protein, which helps the virus enter cells. The protein changes shape after it enters cells, by which point it’s too late: even if our immune system could recognize it, it wouldn’t matter. But its pre-fusion shape, before it enters, is a powerful target. After scientists could see its structure with crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy, they used genetic engineering to mutate the protein and lock it in its pre-fusion shape for a vaccine.

Precision vaccines

The RSV vaccine was also part of a major shift in vaccine technology: it was not the whole virus but an individual protein. Until the mid-twentieth century, the vast majority of vaccines had been made from whole pathogens. Making precise vaccines, containing only a few key ingredients, would improve their safety and widen their breadth.

This approach gradually replaced the Pasteurian method of culturing and weakening a microbe. The first step came in 1890, only a few years after Pasteur’s breakthrough, when the doctors Emil von Behring and Kitasato Shibasaburo discovered ‘serum therapy’. By passively transferring the serum of an infected person or animal to someone else, they could prevent or treat the latterʼs infection.

Their serum therapy tamed diphtheria, whose victims, typically young children, could die of suffocation within days. The bacteria release a toxin that kills throat cells, causing our body to respond by laying a tough, clot-like membrane that can inadvertently seal the airway and choke us. Unfortunately, serum therapy gave only fleeting protection: whatever was in the serum didn’t teach the immune system to recognize and remember the pathogen later on.

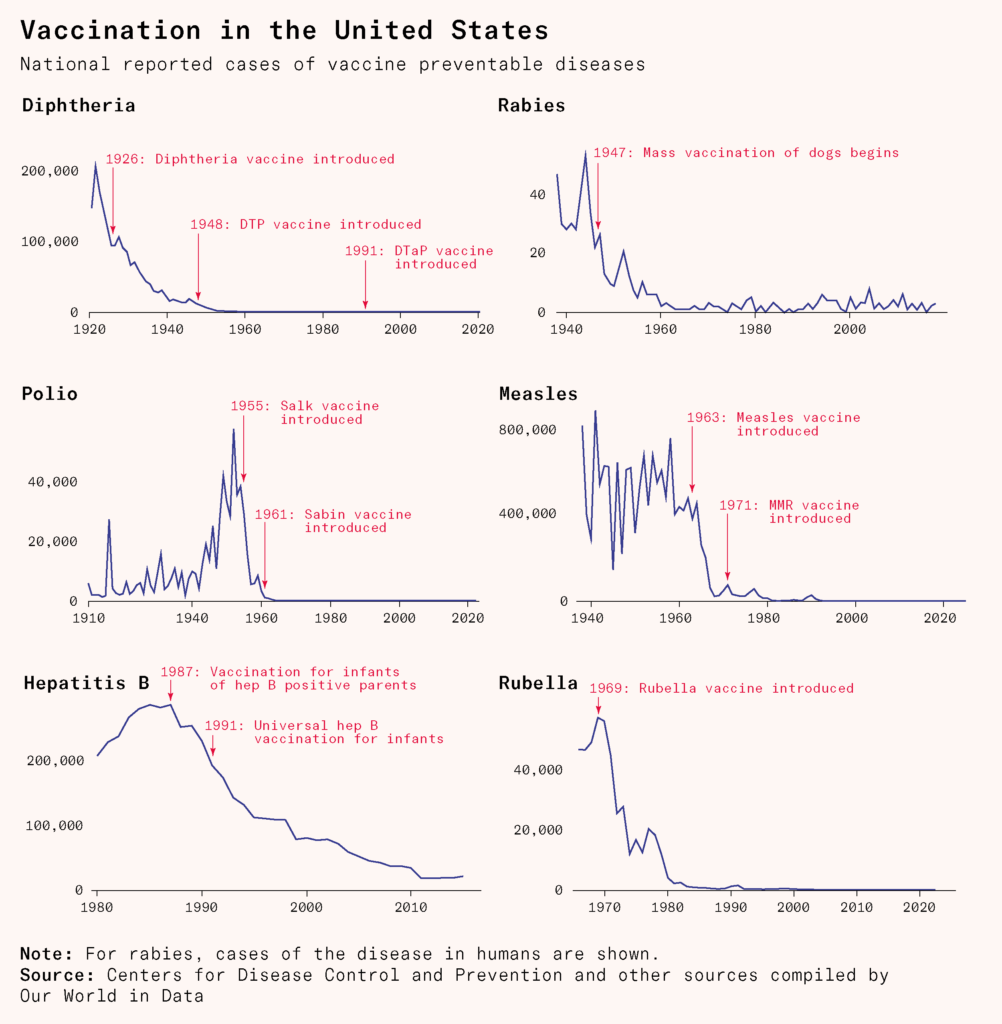

Over three decades later, researchers developed an active, longer-lasting vaccine against diphtheria by inactivating the bacteriaʼs toxins using formalin, while maintaining their ability to stimulate an immune response. Diphtheria cases fell dramatically. It was the first example of what we now call a ‘subunit vaccine’, containing only a particular part – in this case the inactivated toxin – of the bacterium.

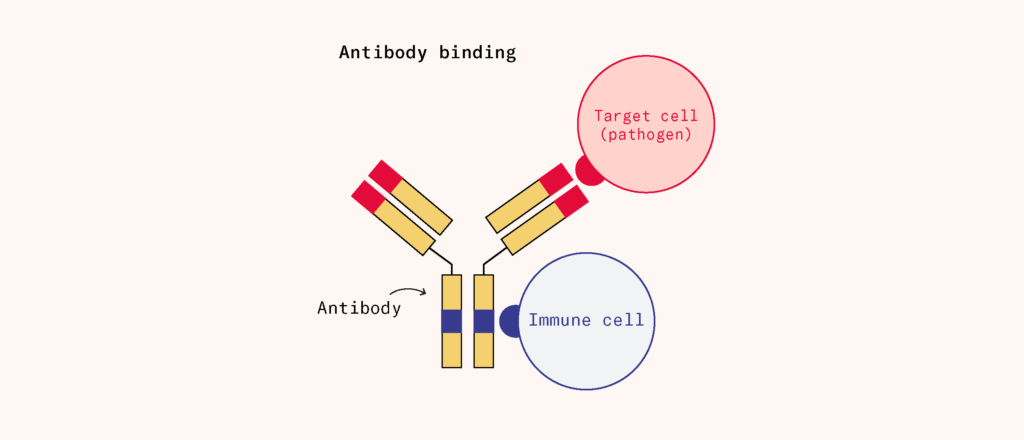

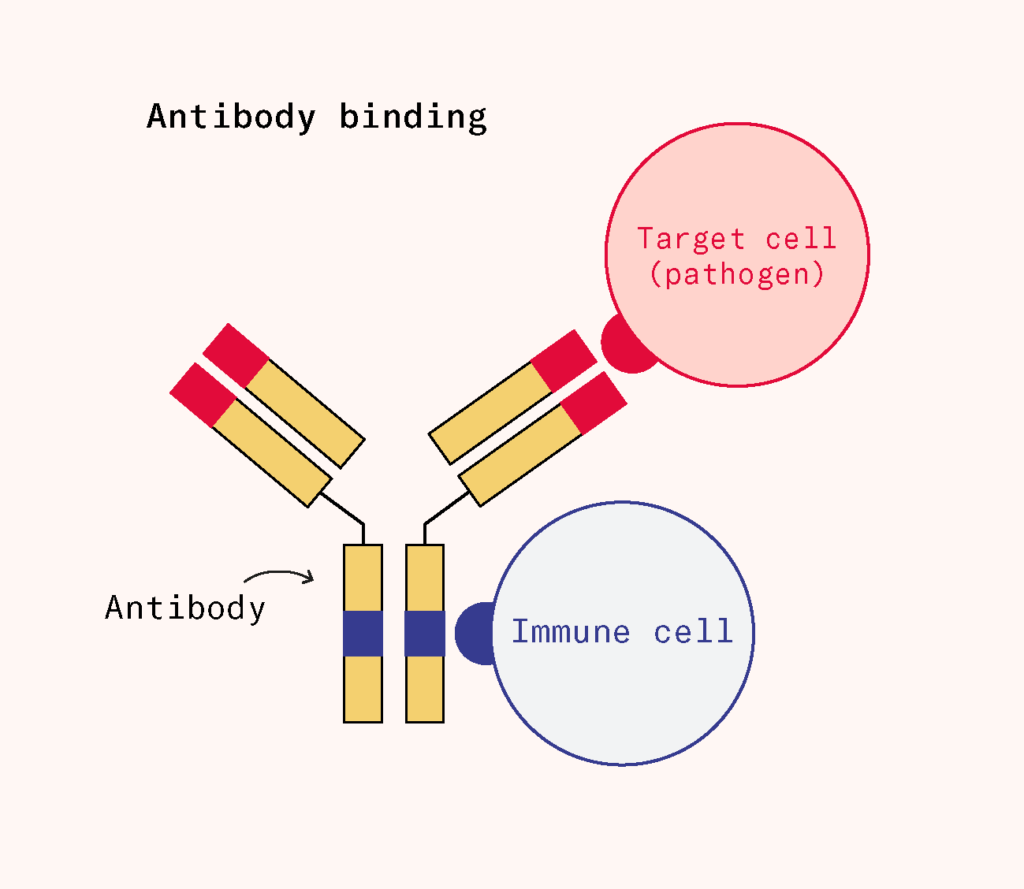

Though serum therapy was being replaced by vaccines, it had also given scientists a key insight: serum carried protective factors that could defend someone against pathogens they had encountered before. Those protective factors included antibodies, which attach to particular parts of the pathogen, called ‘antigens’.

Researchers developed a growing set of tools to detect and quantify antibodies. What they found was remarkable: antibodies weren’t just vaguely anti-foreign, they were highly specific. Tiny differences in the molecular structure of an antigen could lead to entirely different immune responses, as the doctor Karl Landsteiner discovered when he worked out the chemical basis of blood groups. But how could the body possibly generate so much diversity and specificity?

One theory, the ‘instructional’ model, was proposed by Linus Pauling. He suggested that the microbe acted as a template, molding the shape of the nascent antibody to fit it. This seemed to explain the high specificity of the interactions at first. But with more data, the model broke down. Just a single unit of an antigen could generate millions or even billions of antibodies that were exact copies of one another, not what you’d expect if they all required contact. And some were present even before exposure to an antigen, like the natural antibodies people have against other blood groups.

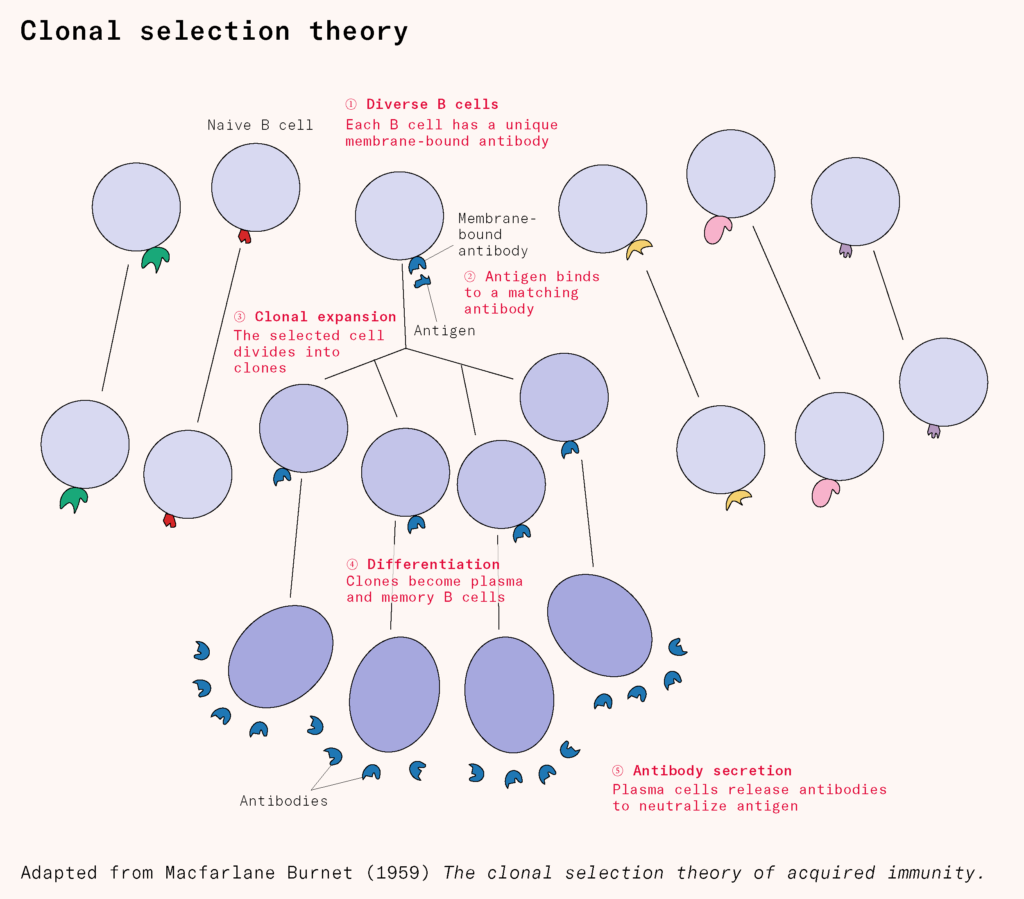

Gradually, the field shifted toward another model, proposed by Niels Jerne, which suggested that antigens weren’t reshaping antibodies: they were being recognized by a pre-existing antibody repertoire. This was refined into ‘clonal selection theory’ by Macfarlane Burnet in 1957: each white blood cell expresses a unique antibody, and when it finds a matching antigen, clones of that white blood cell multiply and release thousands of antibodies per second. The massive diversity of white blood cells, researchers later found out, isn’t encoded from birth – the DNA of developing white blood cells is actively cut, shuffled, and stitched back together during our lifetimes into tens of millions of unique antibody-producing cells, generated continuously after birth, waiting for the right antigen to come along.

This extreme specificity meant the immune system didn’t need the entire pathogen to trigger a response, but only a part of it, the right antigen, to recognize it in the future. It laid the groundwork for an entirely different approach to developing vaccines or improving existing ones.

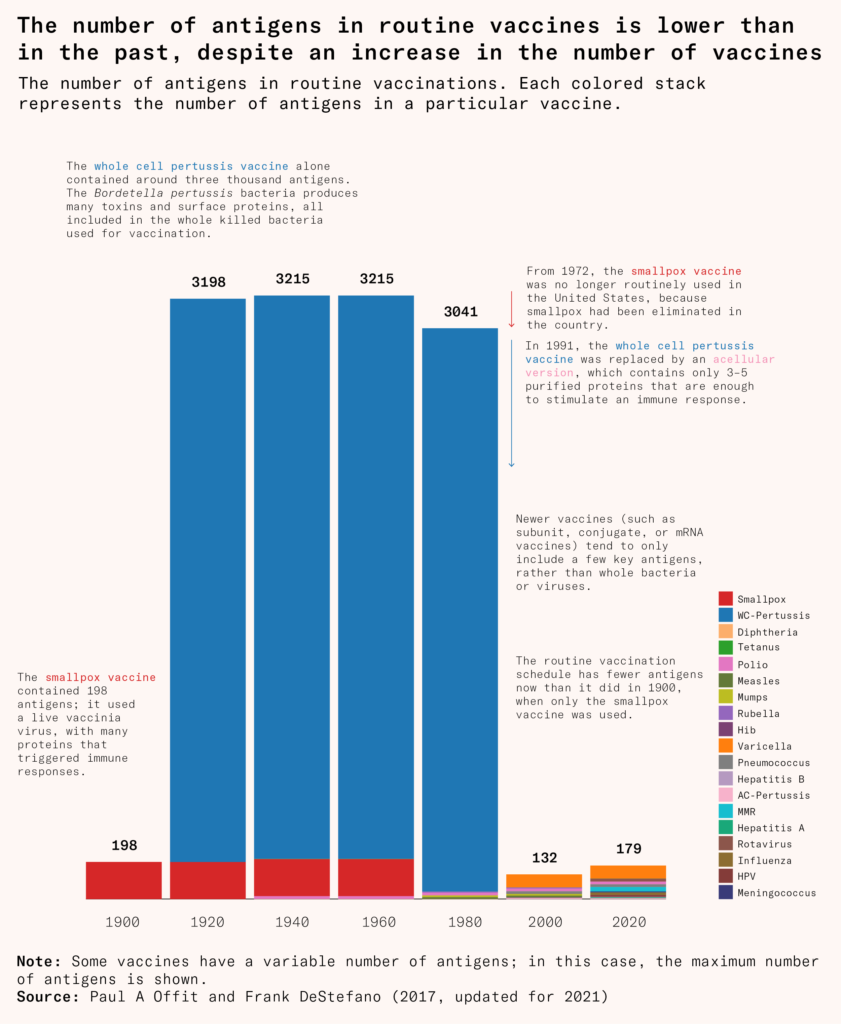

One example was the vaccine against pertussis, or whooping cough, a disease that leaves infants and young children violently gasping for breath. Pertussis vaccines were developed back in 1914, and their rollout massively reduced the spread of the disease. But they also contained the whole bacterial cell and could cause rare side effects. The Bordetella pertussis bacterium has thousands of antigens, and injecting vaccines containing the whole bacterium meant injecting unnecessary material. Rising concern about the safety of the vaccine led to lawsuits in the United States and, in Japan, the government suspended it. As vaccination rates dropped, pertussis cases and deaths rose, spurring an international research effort to develop a better vaccine: one that contained only the antigens necessary for protection.

Yuji and Hiroko Sato, a husband and wife team working at the National Institute of Health in Japan, found two such antigens: pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin. They purified and detoxified them with formalin. The resulting vaccine became part of the diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, which was introduced in Japan in 1981 and later adopted globally.

More and more vaccines have been developed with this approach, as scientists have sifted through pathogens to find only key antigens that are needed for a subunit vaccine. As they’ve replaced older vaccines, the number of antigens that children receive in childhood vaccines has fallen sharply. Children receive more vaccines today, but fewer and more targeted antigens than they did back in 1900, when only the smallpox vaccine was widely available.

Subunit vaccines have many advantages. Without the entire pathogen, there are fewer contaminants, fewer unnecessary antigens, and fewer side effects. They can also easily contain antigens from multiple pathogens, protecting people from all of them at once. But stripping vaccines down to a few components can also come at a cost: the acellular pertussis vaccine, for example, was safer but also less effective, with immune protection waning after a few years.

Over the twentieth century, immunologists discovered new ways to restore the potency that subunit vaccines had lost. They found ‘adjuvants’, such as aluminium salts and oil-based emulsions, that could dramatically strengthen the immune response. They also learned that the way a vaccine’s antigens are presented, the structure, formulation, and delivery, could shape immunity. Step by step, scientists learned to recreate the strength of whole-pathogen vaccines with the safety of their purified descendants.

The genomic revolution

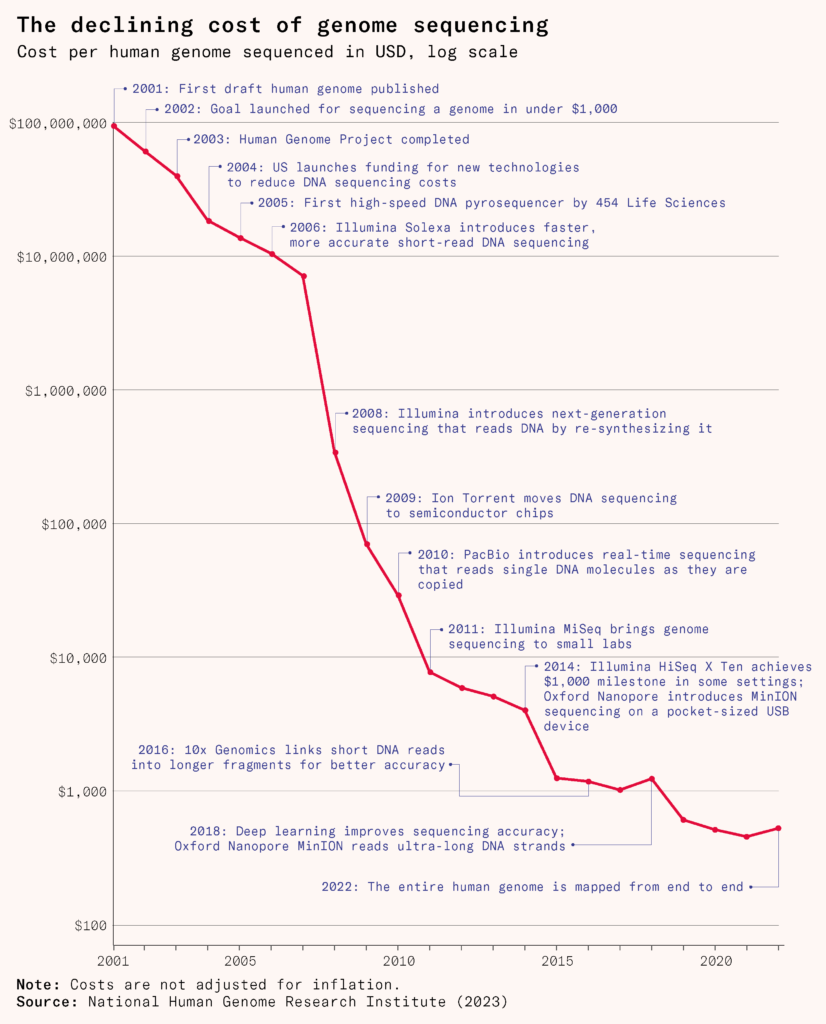

A new era began when scientists stopped merely cultivating viruses and began decoding them. Over the last 50 years, genome sequencing has grown faster and cheaper, and genetic engineering has become ever more precise: the blueprints of pathogens have become both readable and editable, making it possible to rapidly redesign vaccines to match an evolving world of microbes.

In the 1970s, it took weeks or months to laboriously decode the sequence of a single gene. Even in the 1980s, after automated sequencers were introduced, it took days per gene. But by the 2010s, propelled by the Human Genome Project, scientists could read entire genomes in the same amount of time with new sequencers, at a tiny fraction of the cost. Since then, some sequencing devices have been made so compact they can be plugged into a computer like a USB stick.

Scientists can now compare thousands of strains to one another and analyze how changes in a virus’s genetic code weaken it. They found, for example, that only a handful of mutations were needed to attenuate the poliovirus into a vaccine that doesn’t invade nerve cells or cause paralysis. By experimenting and tweaking it further, scientists developed a new, more stable oral polio vaccine.

Sequencing can also help identify better genes to use as vaccine targets. Genes that are conserved across multiple strains of a virus can help make a vaccine that protects against them all; genes encoding proteins on a virus’s surface make for better immune recognition. This approach of finding antigens through genetics, known as reverse vaccinology, produced the first effective meningitis B vaccine in 2013. Finally, sequencing has enabled scientists to track evolving viruses like influenza and Covid-19 in real time in order to update their vaccines.

Alongside these advances, scientists learned to transfer and edit genes between organisms, turning cells into tools of manufacture. In the 1970s, biologists Paul Berg, Stanley Cohen, and Herbert Boyer developed methods to combine DNA from different organisms. This method, called recombinant DNA technology, involved cutting DNA with restriction enzymes and pasting it into vectors, transforming bacteria, yeast, or insect cells into miniature factories that can produce proteins like insulin in bulk.

This solved another problem that subunit vaccines had. In the past, developing them required purifying proteins from viruses grown in eggs or tissues, which was laborious, gave low yields and could contain contaminants. Recombinant DNA technology replaced this process. It helped Maurice Hilleman, who made over 40 vaccines in his lifetime, develop the first recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. It contained only one key surface protein from the virus and was far easier to manufacture than previous versions of the vaccine.

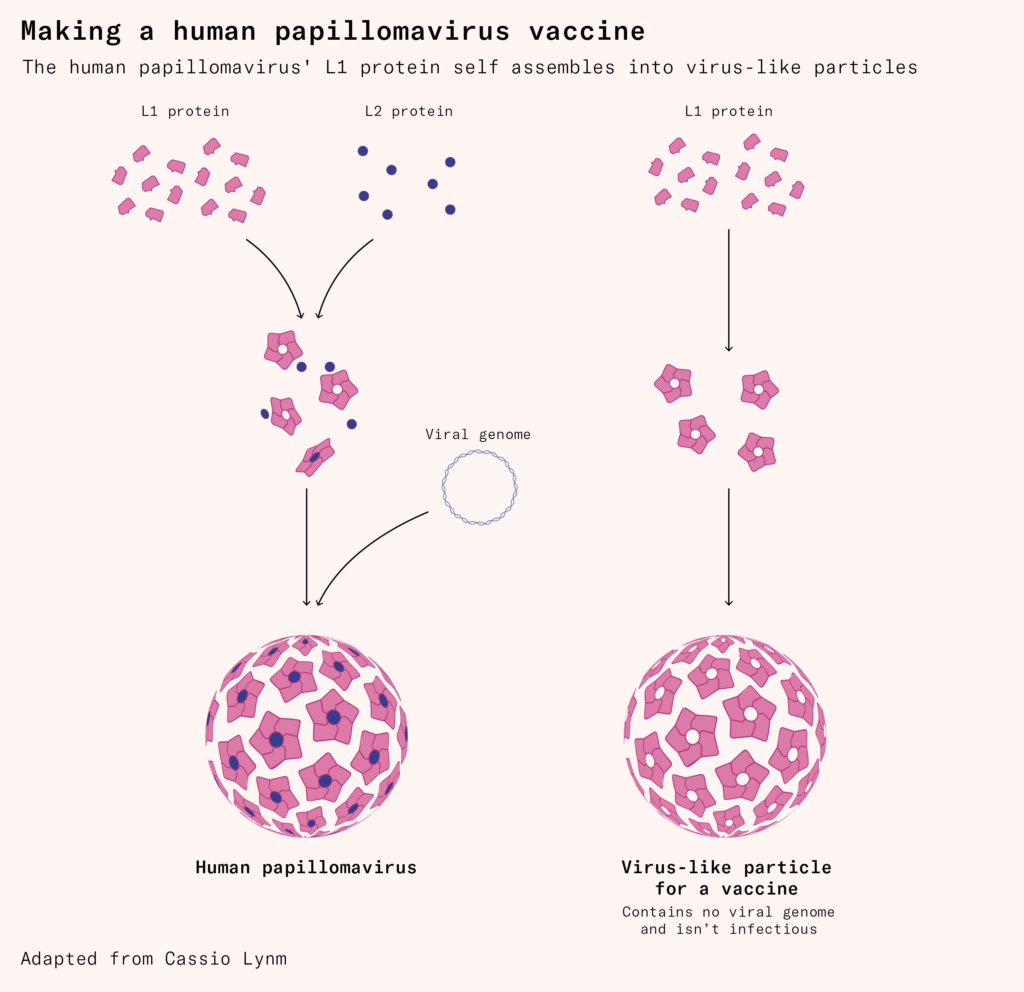

It also helped develop the first human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which contains copies of a protein from the outer shell of the virus. When expressed in yeast or insect cells, these proteins spontaneously assemble into hollow ‘virus-like particles’ that resemble the real virus but contain nothing inside. The immune system responds as though they are genuine viral invaders, giving it the ability to respond swiftly if it encounters the real virus later on.

Recombinant DNA technology can also combine targets from multiple microbes. The HPV vaccine Gardasil-9, for example, protects against nine virus strains by including a key antigen from the surface of each one. In doing so, it protects people from a wide range of HPV infections that can cause cancers of the cervix, vagina, vulva, penis, anus, head and neck.

Not all proteins self-assemble and many arenʼt easy to manufacture this way. Viruses typically use our own cells’ machinery to make their proteins, which assemble in specific ways for the virus to multiply. But viral proteins can end up processed incorrectly when grown in recombinant bacteria or yeast, since they have different machinery. To make recombinant vaccine proteins, scientists often spend years experimenting and optimizing the protein’s shape and structure to develop a vaccine, with each protein requiring its own long optimization process.

A better idea is to bypass microbial factories entirely and make cells in our own body produce the proteins for a vaccine. In the 1990s, scientists tried making DNA vaccines for this purpose, with circular plasmid DNA to deliver the instructions into muscle so it could make vaccine proteins. The idea was promising in animals but inefficient in humans: DNA struggles to enter cells and an even smaller fraction would reach the nucleus for this idea to work.

A more direct route is to use mRNA, which can be translated straight away by our protein-making machinery outside the cellʼs nucleus. mRNA is also transient, producing a protein we can recognize before disappearing itself. But it also triggers strong immune reactions, is chemically fragile before it enters cells, easily destroyed by enzymes. Step by step, these obstacles were overcome: first, in 2005, when the scientists Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman developed a method to tweak it and make it less visible to the immune system, and then in 2014, when Weissman and other researchers developed ‘lipid nanoparticle’ systems to carry, protect, and deliver the mRNA safely into cells.

The result was a rapid, adaptable platform that could be redesigned almost as quickly as new threats emerged: because it bypasses microbial factories entirely, each new vaccine can be formulated and updated within weeks.

In the 230 years since Jenner’s discovery, vaccine technology has changed inconceivably, and many diseases that plagued humanity are mostly forgotten.

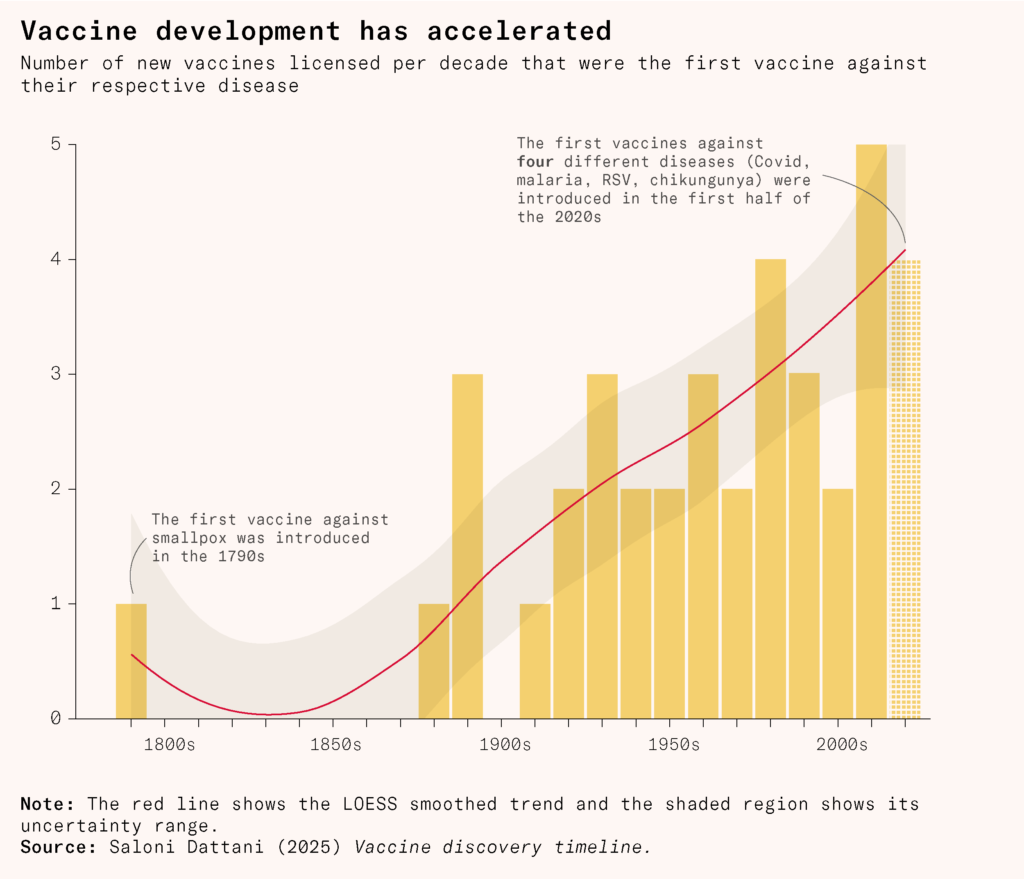

It has become far easier and faster to develop new vaccines. Microbes that were once invisible to us can now be observed at an atomic level. Vaccines were once cultured in animals, then tissues, then cells, and now their individual proteins can be built in microbial factories. They can be engineered to be safer and more precise than ever before.

Biology has had golden ages in the past, as scientists rapidly discovered new microbes, antibiotics, and drugs: microbiology’s golden age developed in the late nineteenth century, while antibiotic development had a golden age in the mid-twentieth century. Meanwhile, vaccine development has actually sped up; in the last five years alone, scientists have developed the first effective vaccines against four additional diseases. If we invest in them, the future holds many more. The golden age of vaccine development lies ahead of us.