Long before modern science, Europeans learned to see their own time as an age of invention rather than decline.

In 1588, Galileo had not yet looked through a telescope. Microscopes, pendulum clocks, barometers, and steam pumps were decades away. Francis Bacon, a member of parliament still in his twenties, was only beginning his writing on science. Robert Boyle wouldn’t be born for another 39 years, Isaac Newton for another 55.

But a subtle shift in perspective was already taking place, heralding the ‘culture of growth’ that would blossom in the coming century. In intellectual circles, Europeans had begun to view their era not as a pale imitation of classical greatness but as a promising new world, blessed with discoveries and inventions the ancients never imagined. For all their brilliance, after all, Aristotle and Cicero knew nothing of the Americas – continents with as many and varied peoples, landscapes, flora, and fauna as Europe, Asia, or Africa. Nor did they enjoy the navigational tools that had made such discoveries possible.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

In the late 1500s, in other words, Europeans started to imagine progress. ‘The first history to be written in terms of progress is [Giorgio] Vasari’s history of Renaissance art, The Lives of the Artists (1550)’, observes historian of science David Wootton. ‘It was quickly followed by Francesco Barozzi’s 1560 translation of Proclus’s commentary on the first book of Euclid, which presented the history of mathematics in terms of a series of inventions or discoveries’.

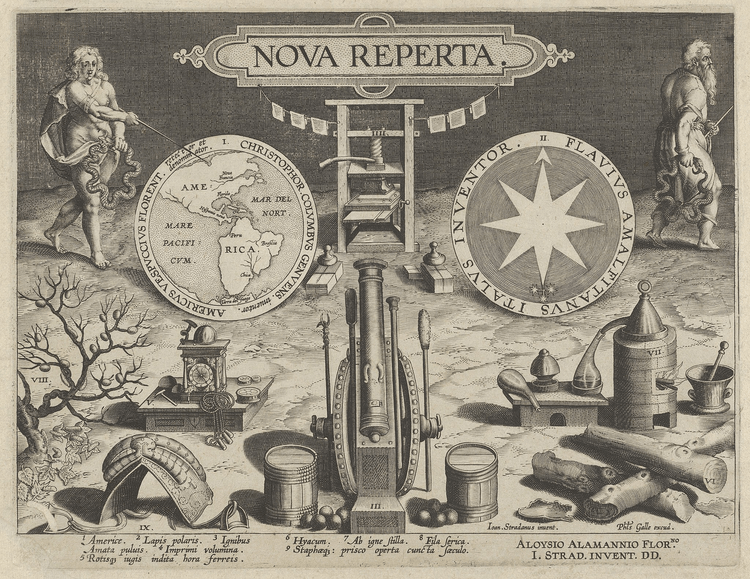

This was the environment in which two Florentines conceived Nova Reperta, whose Latin title is usually translated ‘new discoveries’. One of the earliest works promoting the new attitude – and definitely the most charming – the book is a collection of 19 engravings, each celebrating a discovery or process that was relatively new to Europeans. First published in 1588, Nova Reperta made the argument for progress by showing rather than telling.

Its creators were the Flemish-born painter Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet), a former Vasari apprentice who worked for the Medicis, and his friend and patron Luigi Alamanni, a literary intellectual from a prominent Florentine family. As a sideline to his prestigious commissions for paintings and tapestry cartoons, Stradanus often designed print series on popular subjects such as hunting scenes, horses, and the Passion of Christ. Drawing on Alamanni’s expertise and substantial library, for Nova Reperta Stradanus created meticulously detailed reminders of how the contemporary world differed from antiquity.

The title page serves as a graphic introduction. At the top left, a strategically draped nude woman points to a map of the Americas. On the top right, an old man exits the page, his back to a compass. Each carries an ouroboros, eternity symbolized by a snake eating its tail. She is the future, he the past. ‘The present lies between them’, writes historian Samir Boumediene, ‘the place of contemporary discovery’. Dividing the vertical halves of the page are a printing press and a cannon, flanked by other inventions and discoveries distinguishing modern life, including a clock and a chemical still. Some of these ‘new’ inventions, such as the stirrup, were centuries-old, imported from other cultures, or both. But none were inherited from antiquity.

The book opens with an allegorical scene of Amerigo Vespucci awakening America, who is wearing a feathered cap and little else, from her hammock. The picture includes exotic animals, including an anteater and a sloth, along with a remarkably nonchalant background tableau of a nude woman roasting a human leg on a spit, with another lined up to go. Nearby, a mother and baby look out to sea. The New World is at once strange and familiarly human.

Most of the other illustrations depict busy European workshops: making cannons and gunpowder; setting type and printing books; smithing iron and filing gears for clocks; pressing and refining olive oil; repairing and polishing armor. The invention of oil paint is represented by a painter’s bustling studio. In one scene, people bring mules laden with grain sacks to a water mill; in the next, they journey toward windmills.

Stradanus portrays a world of sociable work and material plenty. His people look well nourished, and everyone wears shoes, except the boy pumping bellows for the distillation fire, who could just be hot. (In a typically whimsical detail, the big toe of a boy lugging a basket of armor peeks out of his left shoe.)

These images represent what is sometimes called Smithian growth, in which wealth arises from expanded markets, the division of labor, and, implicitly, the synergy of new ideas. In Stradanus’s work, argues Boumediene, ‘rather than a new technique being immediately imposed as a discovery, its true effects are revealed over time’, as when the magnetic compass enables bolder navigation of the seas. ‘Its true power can only be measured when its action is combined with others’.

In a sweeter version of Adam Smith’s pin factory, Stradanus shows how one group of workers cuts sugar cane, another slices and loads it into baskets, and, building on another new discovery, a third brings the baskets to a water mill for grinding. From there, the crushed cane goes to a press, turned by two men, which drains liquid into a well in the floor. Still more workers transfer the liquid into big pots continually heated on stoves. Another man pours the thus-refined syrup into molds that, in the final step, are emptied to produce bullet-shaped pyramids of solid sugar.

Specialization also appears in the book’s final, self-referential illustration, where an engraving goes from an initial design to printed pages hung on the wall. ‘By a new art the sculptor carves figures on beaten sheets and reproduces them on a press’, explains the Latin caption. Engraving divides the key stages among specialized designers, engravers (the ‘sculptor’), and a publisher.

For Nova Reperta, these roles were taken by Stradanus, Jan Collaert, and Phillips Galle, a leading Antwerp print publisher and Collaert’s father-in-law.

Less realistic but more inviting than those in the famous Encyclopédie of the eighteenth century, Nova Reperta’s images aren’t meant as how-to guides. They’re entertainment, filled with extraneous details. Birds perch in the eaves of the water mill while chickens peck stray grains. Fashionably slashed silks on a man consulting the cannon makers highlight his well-turned calves and buttocks. The boy cranking the engraving press looks bored; the one pounding ingredients for distillation seems to be eavesdropping. A sleeping dog curls at the feet of the scholar calculating in the magnetic compass image. Nova Reperta doesn’t tell you how to construct a clock from scratch. It lets you enjoy searching out the picture’s many gears and scrutinizing the looks of concentration on the diverse faces.

An afternoon spent with my nose literally in the 1600 edition at the Huntington Library gave me the same sense of immersion as a novel or film. The whiff of leather binding and the soft, strong feel of the rag-heavy paper – so unlike the crisp, fragile stuff of later books – enhanced the feeling of leaving the present behind.

So, alas, did the book’s joy.

After my encounter with the original Nova Reperta, I visited the UCLA library’s special collections to see a 1999 volume with the same title. A limited edition art book, it features black-and-white photographs, sometimes overlaid with blocks of color. Downbeat, semi-poetic meditations on the bleakness of turn-of-the-century life complement the photos. We start on a rural highway lined with telephone poles. Wind turbines, modest by today’s standards, sprout from the surrounding pastures. ‘POWER seduces the land, staking the human presence across the expanse with all the deference of claiming its inevitable own’, reads the text. Late twentieth-century art book collectors will naturally read the human presence as undesirable and foreign to the land.

Instead of buzzing work spaces, the latter-day Nova Reperta highlights the impersonal infrastructure of bridges, railways, and ports, along with the flashing signs of Times Square and displays of military hardware. An open-plan office with exposed brick walls appears abandoned, with only computers and piles of paper files to suggest its normal occupants. This new world is nearly empty of human beings. Gone are Stradanus’s expressive faces.

‘Unlike Stradanus’s original’, explain authors Johanna Drucker and Brad Freeman in the introduction, ‘our response barely shows the details of bodies, people, or processes, but rather, the outward manifestation in the more familiar forms of landscape conspicuous for the invisibility of labor and relations of production’. The only hints of happiness are in the faces of a family leaving McDonald’s, who seem to represent consumerist delusion.

Just as the original Nova Reperta captured an intellectual moment, so does the 1999 version. The authors explain, drawing a midcentury comparison:

In his 1953 introduction to the Burndy Library reprint of Nova Reperta, Bern Dibner wrote, ‘The boon of the physical sciences stands unquestioned’. His sensibility was closer to that of Stradanus, nearly four hundred years earlier, than it is to ours. Half a century later, it is as difficult to share Dibner’s unqualified endorsement as it is to feel a sympathy with his opening statement, ‘Today we are impatient with Science for not yet having done the things we expect from it’. However, invoking the term ‘science’ as a monolith whose contributions are unqualifiedly positive can no longer pass without question. Our distance from Dibner and Stradanus is marked by a poignant awareness of their lack of attention to the price of the global expansion of consumer culture combined with unregulated exploitation of the environment.

In response, their version inverts the supposed error, substituting relentless negativity for gratitude and wonder. A generation after its publication, the twentieth-century Nova Reperta seems eye-rollingly clichéd. Stradanus, meanwhile, still offers fresh delights.