For centuries it was a poison. Then colchicine rewrote treatment for gout, heart disease, and later, the debate over drug exclusivity.

In the summer of 1760, a French military officer named Nicolas Husson was brewing his Eau Médicinale, a medicinal draught that would eventually find its way across the Atlantic to Benjamin Franklin’s Philadelphia doorstep. Franklin, tormented by gout and desperate for relief, had heard whispers of this mysterious European remedy. He could not have known that he was importing one of humanity’s oldest medicines, recorded as a poison roughly around 1500 BC, and that it would, more than two centuries after Franklin’s death, prevent heart attacks in American patients.

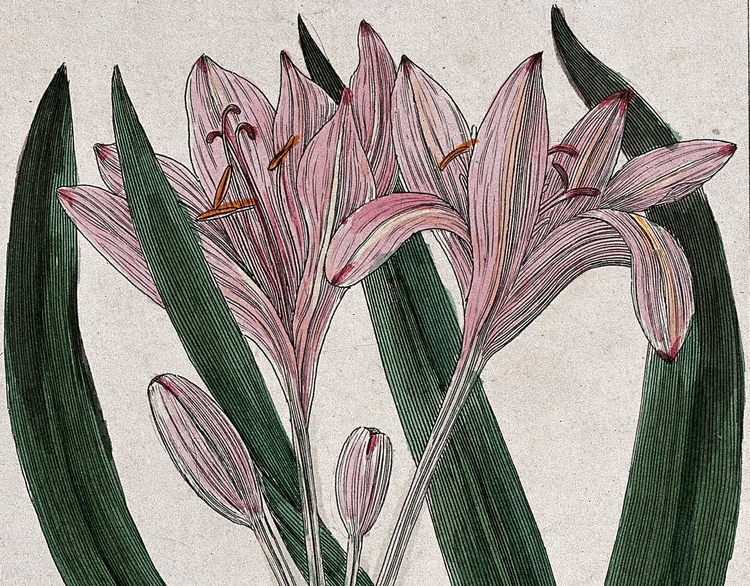

Colchicine is extracted from the autumn crocus, a purple flower native to Europe, and its story spans three millennia of medical history. Today, it stands as one of the few substances that can claim both ancient pedigree and modern FDA approval, having navigated the treacherous waters of contemporary pharmaceutical regulation to emerge as a treatment for gout, rare genetic diseases, and cardiovascular conditions.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

The origin story

The earliest surviving reference to colchinine appears in the late fourth century BC, when botanist Theophrastus wrote of a deadly plant called ephemeron, meaning ‘one-day killer’. By the first century AD, Dioscorides had given it the name that stuck: kolchikon (‘plant from Colchis’) and later called colchicum, warning it ‘kills by choking, similar to mushrooms’. For the next 1,500 years, Western medicine treated colchicum strictly as poison. Medieval herbalists warned against its use; renaissance physician John Gerard declared its roots ‘very hurtfull to the stomacke’.

This reputation began to shift in the late eighteenth century, when French army officer Nicolas Husson created a wildly popular secret gout remedy called Eau Médicinale. Selling for the equivalent of 22 shillings per tiny bottle, then a fortune, the mysterious potion baffled Europe’s chemists, who guessed its active ingredient might be everything from white hellebore to digitalis to tobacco.

In 1814, Englishman John Want finally solved the puzzle through a combination of scholarly research, chemical analysis, and possibly industrial espionage, reportedly obtaining information through a nursemaid who had previously worked for Husson. Want identified colchicum as the secret ingredient and published his findings in medical journals, sparking a revolution in gout treatment. The plant physicians had avoided for nearly two millennia had suddenly become their most effective remedy for gouty attacks.

In medicine, as in chemistry, dosage makes the poison. Colchicine binds to an essential protein that forms the skeleton of cells – tubulin – and prevents the formation of microtubules, which make up the scaffolding that enables everything from cell division to the movement of cells toward sites of injury. By disrupting this process, colchicine causes cascading effects. Neutrophils, which are the body’s first-line inflammatory responders, find themselves unable to move, to attach to the walls of blood vessels, or to release critical signals that help in wound repair and inflammation control.

What makes colchicine compelling as a drug is that it accumulates specifically in neutrophils, which are less able to pump the drug out as they have limited quantities of a protein, P-glycoprotein. This makes the drug able to reduce inflammation at doses that have minimal side effects, even though its ‘therapeutic window’, the dose range at which it can be safely used, is narrow. The same mechanism it uses to halt inflammation also explains the drug’s most notorious side effect: by blocking microtubules, colchicine interferes with cell division, which disrupts rapidly dividing tissues in the gut and bone marrow. The gut relies on constant cell renewal to maintain its protective lining, so when this process is disrupted, it suffers intestinal inflammation and damage. Hence the legendary diarrhea that has plagued colchicine users for millennia.

The clinical renaissance

Despite centuries of use, rigorous clinical evidence for colchicine remained scarce until recent decades. The modern renaissance began in the 1970s, when doctors discovered that daily colchicine could almost entirely prevent the recurrent fever and inflammatory attacks of Familial Mediterranean Fever, a rare inherited autoinflammatory disease, and help prevent secondary amyloidosis, an often fatal complication of the disease where abnormal proteins accumulate in vital organs. This finding established that colchicine was not just an old gout remedy but also a precise anti-inflammatory drug.

The pivotal moment was the AGREE trial, published in 2010, the first modern randomized controlled trial of colchicine in acute gout attacks. The study revealed that a low-dose regimen – 1.8 milligrams total over one hour – was nearly as effective as the traditional high-dose regimen of 4.8 milligrams over six hours in aborting gout attacks, while producing far fewer toxic side effects.

More surprisingly, colchicine has found new life in cardiology. Reasoning that the drug’s anti-inflammatory properties might benefit patients with pericarditis (inflammation of the lining around the heart), Italian researchers conducted a series of landmark trials beginning in 2005. The ICAP trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013, showed that adding colchicine to conventional therapy halved the rate of pericarditis recurrence, from 37 to 16 percent. The drug’s impact on pericarditis is an example of successful drug repurposing: finding new uses for established drugs.The cardiovascular applications expanded further as researchers investigated colchicine’s potential benefits in treating patients with coronary disease. The LoDoCo2 and COLCOT trials demonstrated that a daily 0.5 milligram dose could reduce cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks and strokes, by around 30 percent in patients with stable coronary disease and by around 23 percent after myocardial infarction.

The cost of compliance

Despite its eventual success, colchicine’s drug’s regulatory journey has also become a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of pharmaceutical policy.

For decades, colchicine existed in a regulatory gray area: widely used but never formally approved under modern FDA standards. It was available from multiple generic manufacturers at remarkably low cost, often mere pennies per pill.

This changed with the FDA’s Unapproved Drugs Initiative, launched in 2006 to bring older, unapproved drugs into compliance with contemporary standards of safety and efficacy. The initiative offered companies a period of market exclusivity, in return for conducting rigorous studies to confirm their effects and thus secure FDA approval for these legacy drugs. Philadelphia-based URL Pharma identified colchicine as a prime opportunity: the drug was widely prescribed, particularly by rheumatologists, and its safety risks at higher doses were well-documented. This suggested that a modern approval could both improve patient care and prove commercially valuable.

URL Pharma, through its subsidiary Mutual Pharmaceutical, conducted the required studies, including absorption and metabolism tests and the AGREE trial in acute gout. Based on these data, the FDA officially approved colchicine for the first time in July 2009, under the brand name Colcrys. The approval covered two indications: the treatment of acute gout flares and the prophylaxis of Familial Mediterranean Fever. Notably, because FMF qualified as a rare disease, Colcrys was granted seven years of orphan exclusivity, an extended period to reward the development of drugs for rare diseases, and FMF patients faced the $4.85‑a‑pill brand until 2016, even after cheaper generics began reentering the gout market. Meanwhile, the data on gout, not a rare disease, earned URL only a three-year term for that usage.

Critically, upon approval, the FDA ordered all other manufacturers to cease marketing unapproved colchicine tablets, effective October 2010. URL Pharma had secured a complete monopoly on oral colchicine in the United States.

The regulatory victory came with a cost to patients. Overnight, colchicine prices soared from approximately ten cents per tablet to five dollars, transforming an affordable generic into a luxury medication.

The pricing strategy sparked fierce political backlash. In 2011, Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio, along with Senator Herb Kohl of Wisconsin and Representative Henry Waxman of California, publicly accused URL Pharma of price gouging and exploiting the Unapproved Drugs Initiative. If three million gout patients required daily therapy at the new pricing, the annual cost would approach eleven billion dollars. This was wildly disproportionate to the tens of millions URL Pharma had spent on clinical trials to secure approval for a drug that had been in continuous use for millennia.

URL Pharma defended the pricing by pointing to patient assistance programs and emphasizing the value of ensuring a uniform, FDA-vetted product with updated safety guidelines. The company noted that the approval process had led to important safety improvements, including clearer warnings about drug interactions and revised dosing guidelines for people with kidney problems, changes that could prevent potentially fatal complications. The FDA and rheumatology experts acknowledged these safety benefits, though many questioned whether they justified the price increase.

The controversy intensified when lawmakers discovered that over twenty generic manufacturers had been producing colchicine before the Colcrys approval, and had all been forced to cease production. The Unapproved Drugs Initiative, originally conceived as a program to improve drug safety and quality, was increasingly criticized as a mechanism that allowed companies to game the system, improving drug regulation at the expense of patient access.

Despite its controversies, Colcrys quickly became a lucrative product, with annual sales reaching approximately $430 million in 2011. This success attracted attention from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Japan’s largest drugmaker, which agreed to acquire URL Pharma for $800 million dollars upfront in April 2012. For Takeda, the acquisition offered immediate revenue boost and strategic synergy with its existing gout portfolio that included Uloric, a drug for chronic gout management. The deal allowed Takeda to offer a complete suite of gout therapies: Uloric to lower uric acid levels and Colcrys to prevent acute flares.The monopoly eventually eroded as competitors found ways to challenge Colcrys’s exclusivity. In 2014, Hikma Pharmaceuticals obtained FDA approval for a colchicine capsule called Mitigare, relying on published literature rather than conducting new trials. In response, Takeda sued both the FDA and Hikma, unsuccessfully, arguing that the approval violated Colcrys’s exclusivity rights. By 2015, the temporary exclusivity had run out, and generic colchicine tablets returned to the US market, though prices remained several times higher than the pre-2009 generic cost.

The future

The Colcrys episode had lasting implications for pharmaceutical policy. The pricing controversy, along with similar cases involving other drugs brought under the Unapproved Drugs Initiative, led to growing criticism of the program. In late 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services announced it was ending the initiative altogether, partly due to the cost inflation seen with colchicine and other drugs. The program had achieved its stated goal of improving drug safety and quality, but at a cost that many deemed unacceptable.

There are likely many more long-standing generic drugs that could be repurposed, but at the moment, there is little incentive to invest in the research and trials needed to discover them. Many of the problems with Colcrys could have been avoided with different policy designs, such as shorter exclusivity periods, prizes, or vouchers.

Colchicine’s evolution from a crude plant extract to a precision anti-inflammatory drug is not an unusual one, as various ancient herbs have been refined and improved with better tools and understanding. But its story shows how specific policy decisions can change the calculus for investment and pricing, resulting in unintended consequences that affect the lives of millions of patients.