Many Victorian cities grew by tenfold in a century. Could ours ever do the same?

In the nineteenth century, cities grew quickly. Between 1800 and 1914, the population of Berlin’s metropolitan area grew twenty times, Manchester’s twenty-five times, and New York’s a hundred times. Sydney’s population grew around 240 times and Toronto’s maybe 1,700 times. Between 1833 and 1900, Chicago’s population grew around five thousand times, meaning that on average it doubled every five years.

Raw population growth understates the speed of expansion. The number of people per home fell, and, in Britain and America, the size of the average home roughly doubled. At the same time, those homes fit on a smaller share of land, with huge swaths given over to boulevards, parks and railways. The expansion in surface area was thus often several times greater than the expansion in raw population. Meanwhile, real house prices remained flat, while incomes doubled or tripled, generating a huge improvement in housing affordability. Far more people were enjoying far larger homes for a far smaller share of their income.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

As well as becoming bigger, nineteenth-century cities became better. Their streets were wider, straighter, and better structured as a network. By the end of the century, they had vast systems of public transport. Incredibly, the average speed of public transport in 1914 was about the same as it is today, while its coverage was often far greater. Nineteenth-century urbanism had many of the features that urban designers fight for now, like mixed use, perimeter blocks, and gentle density. And, at least to our eyes, nineteenth-century cities are beautiful. Neighborhoods dating from before 1914 tend to command a price premium today, and tourists travel thousands of miles to walk their streets.

Western cities today grow much more slowly. Between 2010 and 2020, New York’s, London’s and Paris’s metropolitan areas grew by an average of 0.6 percent per year, while even the fastest-growing cities, like Houston and Dallas, grew by around two percent per year. If sustained for a century, New York, London and Paris would grow 1.8 times, and the Texan outliers sevenfold.

This sluggish growth rate has generated intense housing shortages. Tackling them may require learning from the city planners of the nineteenth century. The whirlwind pace of nineteenth-century expansion was underpinned by a distinctive approach to urban government, including a fundamental right to build when it was profitable to do so, tolerance and even mandating of infrastructure monopolies, and willingness to charge fees at profit-making levels to fund urban infrastructure, whether sewerage, water, buses, trams, metros, gas, or electricity.

We can imagine what, say, New York City might look like if this system had endured. The serried towers of the Financial District might extend the length of Manhattan; surrounding it might be an endless Brooklyn of five-storey brownstone row houses, stretching all the way from the Hamptons to New Brunswick, serviced by 50 metro lines. New York might still be the world’s largest city, a genuine competitor to the 65 million living in the Pearl River Delta. Perhaps the great cities of the West may yet return to this trajectory. But if they wish to, they would do well to revisit how they managed it once before, not so very long ago.

Streets and drains

Urban planning involves controlling development over a geographical area to ensure that the area works as a whole. Street networks are perhaps the most obvious example of how this can be useful. If streets do not join together or go to places where people want to go, they are useless. If they are too narrow or too winding, their usefulness is severely compromised. Almost the entire value of a given unit of road depends on its being connected to other units of road.

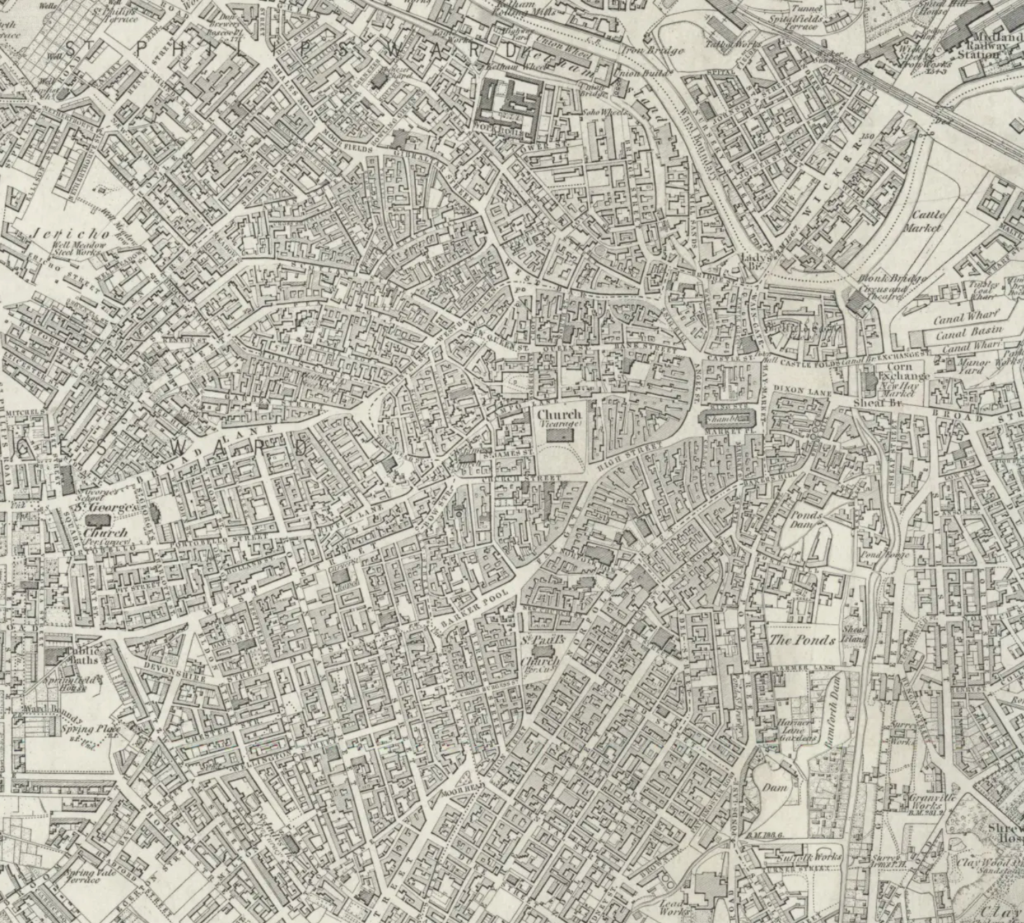

Disastrously unplanned street systems often develop in areas with weak governance, with landowners creating masses of access roads that fail to join up into a coherent network. In early nineteenth-century Sheffield, nearby coal reserves led to rapid urban expansion without a proper municipal government to manage it. In the southern parts of the city, ownership was sufficiently unified that the landowners were incentivized to lay out a fairly coherent street grid by themselves, but in the north, a congested mass of narrow lanes, bizarrely shaped blocks and gloomy cul-de-sacs emerged, with extremely poor overall circulation.

Where they existed, municipal governments generally recognized the need for an integrated street network and acted vigorously to guarantee it. The clearest cases of this were the great extension plans, in which the authorities literally drew a map dictating where future streets would go as the city expanded. Nearly all major American and Canadian cities did this, using simple but effective grid plans which created convenient square blocks and highly interconnected street networks. The canonical early example is the Commissioners’ Plan for New York in 1811, which designated a future street network covering the whole of Manhattan at a time when only the southern tip was built up. All major American cities, except Boston and Washington DC, emulated it.

Europeans generally regarded American gridiron plans as comically ugly. Charles Dickens visited Philadelphia in 1842 and described its street grid as ‘distractingly regular’, remarking that ‘after walking about it for an hour or two, I felt that I would have given the world for a crooked street’. Only a handful of major European extension plans worked this way, the most famous being the Plan Cerdà for Barcelona’s Eixample neighborhood. Its grid was unpopular with local people, who preferred an alternative scheme closer to normal European practice, and the grid had to be forced on the city by the government in Madrid.

Most European extension plans started from a framework of axial boulevards, straight, tree-lined streets terminating on squares, monuments, or public buildings. Boulevards were designed to enable easy wayfinding and swift movement of carriages and public transport. Between the boulevards, side streets were usually plotted on a modified grid, a looser version of the system used in the United States. Berlin, Madrid, Rome and Milan were all governed by extension plans of this kind, as was Washington DC, uniquely for an American city. The most famous city planner of the time, Josef Stübben, drew up extension plans of this kind for nearly 100 cities as far afield as Bilbao and Poznań.

The regime for enforcing extension plans varied, but there was a dominant model, variants of which were used in Germany, Italy and Spain. As soon as the extension plan was set, development on the designated street alignments was banned. Development on the remaining land in the plan area was conditioned on the landowners’ grading the alignments, partly covering the costs of surfacing them, and then ceding them to the authorities. Because development was extremely profitable for landowners, this mechanism incentivized them to implement the city’s extension plan themselves.

Governments used compulsory purchase only occasionally, generally for major arterial roads or for dealing with holdouts. In Berlin, for example, compulsory purchase was used in the development of a handful of key boulevards like the Frankfurter Allee, Leipziger Straße, Potsdamer Straße and Schönhauser Allee, but everything else was left to landowners to lay out in their own time. This helped to minimise controversy. American cities initially used a more aggressive system of compulsory purchase, but over time they tended to adopt the continental approach too.

In Britain, France and Portugal, the authorities generally did not produce extension plans for entire cities. Smaller cities often lacked comprehensive extension plans even in Germany and Spain, and there were also cases where development spilled out beyond the area governed by an extension plan into unplanned territory beyond it, like Gràcia in Barcelona.

The lack of an extension plan definitely had an effect on the character of cities and neighbourhoods. Overall road share tends to be lower: for example, central New York has 36 percent road share against 30 percent in London and 29 percent in Paris. The contrast is particularly striking in the case of arterial roads. Most of London’s arteries today are basically rural lanes from the Middle Ages, so they tend to have only two lanes for traffic. This means dedicated lanes for buses, trams or bicycles are rare. In a planned city like Madrid, Budapest, Milan or Berlin, the arterial boulevards are much wider, and dedicated lanes are standard.

However, the contrast between the planned and organic models should not be overstated. British and French authorities did not have overall network plans, but they did plan streets on an ad hoc basis. The famous Haussmann boulevards in Paris are examples of this: the authorities compulsorily purchased swaths of land and laid out arterial roads on them. These planned streets never made up more than a small share of the urban road network, but the overall system of circulation partly depended on them. The British authorities often gave private companies powers to compulsorily purchase designated alignments, lay out roads, and then toll travellers to make back the cost (so called ‘turnpike roads’). In London, Euston Road, Brixton Road, Harrow Road, Finchley Road and Old Kent Road are among the many examples.

Controversially, these planned roads often cut through existing urban fabric. Medieval and early modern cities had not been built to deal with a large flow of wheeled vehicles, which meant they frequently became traffic chokepoints. Municipal authorities responded by compulsorily purchasing and demolishing urban buildings to widen roads or to open up entirely new ones. The Parisian examples of this like the Rue de Rivoli and the Boulevard de Sebastopol are the most famous, but most major European cities have examples, like the Gran Via in Madrid, Victoria Street in London and the Via Nazionale in Rome. Cuttings involved a brutal loss of ancient fabric and displacement of existing residents, but they were extremely successful in improving circulation.

All countries, including Britain and France, heavily regulated the streets that they did not plan themselves. Generous minimum widths were widely enforced. In London, all roads had to be at least 12 meters in width. This is wide enough that cars can be parked on both sides of the road today while still leaving enough space for cars to pass each other between them. Elsewhere, the minimum street was wider still. Berlin’s streets were at least 22 meters (72 feet); New York’s cross streets were 60 feet (18 meters) and its avenues were 100 feet (30 meters). This generosity is somewhat astonishing given that very few people in the nineteenth century owned private carriages, and that those who did always stored them off-street.

Public regulations also controlled the kind of networks that developers could lay out in countries or areas without a formal extension plan. One example of this is restrictions on cul-de-sacs. For a developer with a small parcel of land, cul-de-sacs are often the value-maximizing street type, because they exclude disruptive through-traffic while still giving residents road access. For the city as a whole, however, cul-de-sacs are troublesome: if everyone excludes through-traffic, nobody can get anywhere.

Many nineteenth-century authorities therefore tightly restricted them: in London, for example, cul-de-sacs longer than 60 feet were banned outright, and shorter cul-de-sacs were allowed only if they were wider than they were long (so really courtyards or closes rather than true dead-end streets). Regulations of this general kind were ubiquitous in nineteenth-century cities, such that street networks are normally more a function of public regulation than market forces, even when they were not strictly planned by the state.

Overall, then, the level of public planning of street networks varied from high to absolute. There is abundant evidence for the economic value of these interventions. A generous road endowment is extremely useful: a World Bank study found that congestion in Cairo alone costs Egypt around 4 percent of its GDP, while a United Nations study estimated that congestion costs EU and American economies just 1.4 and 0.7 percent respectively. UN-Habitat recommends that cities preserve at least 30 percent of surface area for roads, very much in line with nineteenth-century norms. The structure of these roads also has demonstrable effect, with several careful studies finding that gridded networks generate higher property values than unplanned ones.

Only one other kind of infrastructure was publicly planned and funded to the same extent as streets: drains. Up to about 1850, sewage was generally stored in brick-lined cesspits and then removed by specialized businesses known as ‘gong farmers’, who sold it for use as agricultural fertilizer. Greywater (water used for washing and cooking) was usually poured into open channels in the street, down which it flowed into rivers. Gong farming cannot have been the most pleasant occupation, but it was often quite profitable, and the farmers who made use of its products formed a notable lobby group against the development of sewerage. When Düsseldorf excavated a sewerage system, the gong lobby prevailed upon the authorities to forbid its use for human waste, and for about twenty years Düsseldorf’s expensive new system was used only for greywater.

Popular historians like to tell horror stories about the old system, but in smaller cities it seems to have worked well enough, and consumer demand for sewerage connections was surprisingly low. It survived well into the postwar era in the cities of Japan, as well as, curiously, in the Australian city of Brisbane. A version of it is still widely used today in rural areas, though most cesspits were gradually replaced by septic tanks. In the eyes of contemporaries, the great problem with the system was its openness to abuse: some people illegally dumped sewage into rivers and canals, and others failed to maintain cesspits properly, leading to the contamination of urban groundwater and ultimately to the rising incidence of cholera, typhoid and dysentery. The increasing abundance of running water and the hardscaping of ever wider urban areas also led to increasing flood risk.

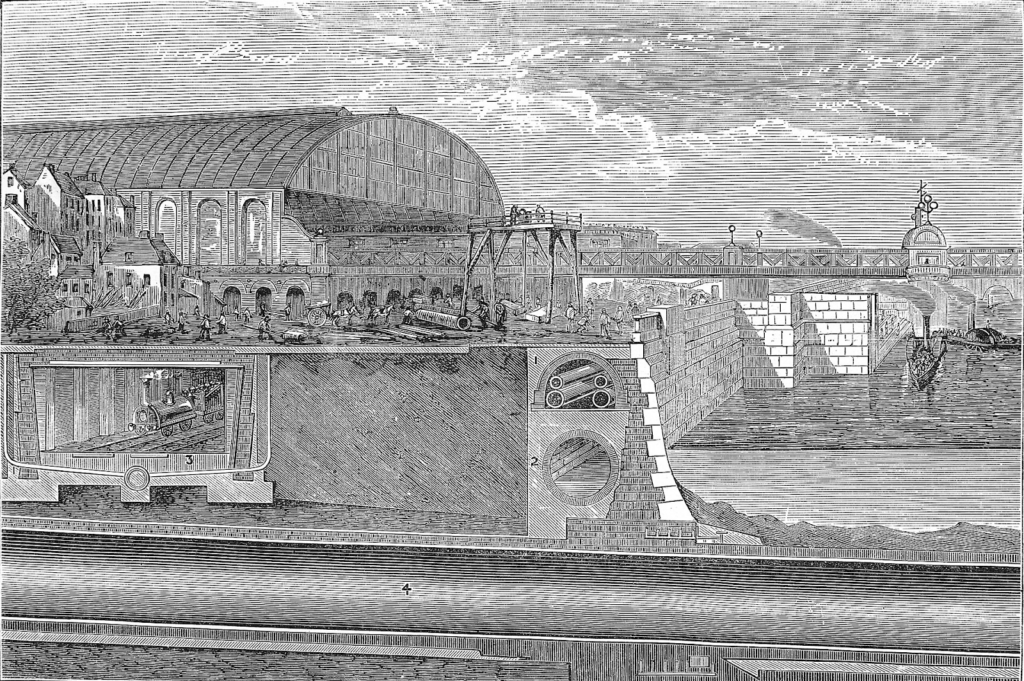

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century, municipalities embarked on immense projects to develop modern sewerage systems. Paris’s system was laid in the 1850s and 60s as part of Haussmann’s interventions. In London, the great engineer Joseph Bazalgette reclaimed a stretch of land 30 meters deep from the Thames. On top of this land he ran a street (the Victoria Embankment), and within it he ran a huge sewerage pipe, which intercepted the various polluted drains and streams of London before they reached the river and whisked their contents away to the east. New York developed its drains in a more piecemeal fashion between the 1860s and the 1890s. These projects were triumphantly successful in reducing disease, and were viewed with great pride.

The main benefits of drains were public goods like clean groundwater, less flooding, and fewer epidemics. No individual consumer was willing to pay for these by themselves, and as a result private enterprise only ever played a limited role in the emergence of drainage systems: developers of new housing were often required to lay drains and pay for a connection to the municipal system, but the core trunks of the system were always publicly developed and funded through municipal taxation. Drains seem to sit with navies, law courts and diplomats as one of those services where a prominent state role is most clearly inevitable.

Trains, trams, buses, water, gas and electricity

We have seen that nineteenth-century streets and drains were delivered through public planning that was at least as activist as that which is practiced today. These made up only a modest share of the period’s infrastructure investments, however. A citydweller in 1800 was still living with infrastructure that was basically medieval in character. By 1914, middle-class people (certainly) and working-class people (increasingly) enjoyed vast systems of buses, trams, trains, gas, running water and electricity.

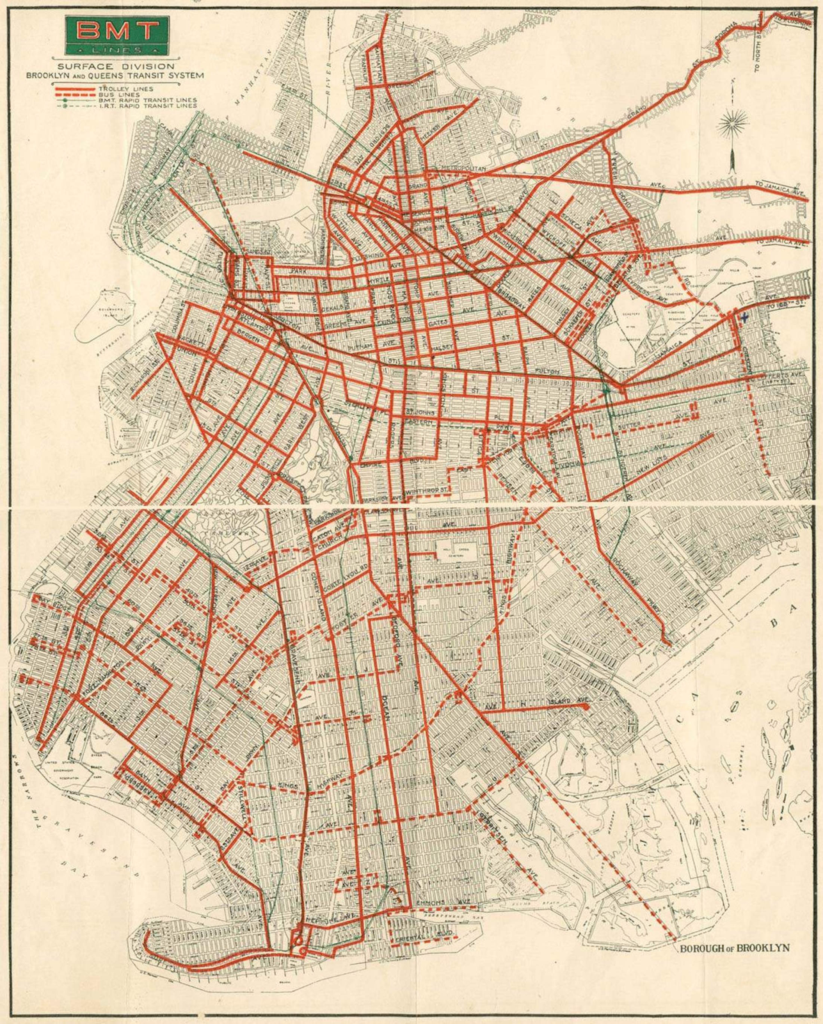

In the case of public transport, in fact, provision in 1914 was often better than it is now. The United States had some 975 electric tram networks with a total length of about 45,000 miles, longer than all the rest of the world’s tramlines put together. Although the maximum speed of these trams was slower than that of modern vehicles, the absence of congestion on the roads meant they operated at remarkably similar speeds. In New York City in 1914, the average speed of a tram was 8 miles per hour, while today the average for New York local buses is 7.8 miles per hour.

These systems were the product of public intervention, but a very different kind of intervention to that which was used for streets and drains. Transport and utility infrastructure has two features that mean it often requires special regulatory treatment. First, many kinds of infrastructure have huge positive spillover effects. If I take a solitary trip on a railway to visit a woodland, then the trip is valuable only for me, and the railway company is in the same position as any other consumer-facing business to capture that value through a fare. If I take a trip to visit my grandmother, my trip is valuable for both of us, but the railway has no way of capturing the value it has for her because it cannot charge her for my journey.

This is why transport infrastructure has such large positive spillover effects: we do not just travel for its own sake, we travel to others – family, clients, businesses, friends – for whom our presence is valuable. Transport providers can usually capture only the value of travel to travelers, not to those they visit. This is why the free market often supplies less transport infrastructure than is socially optimal.

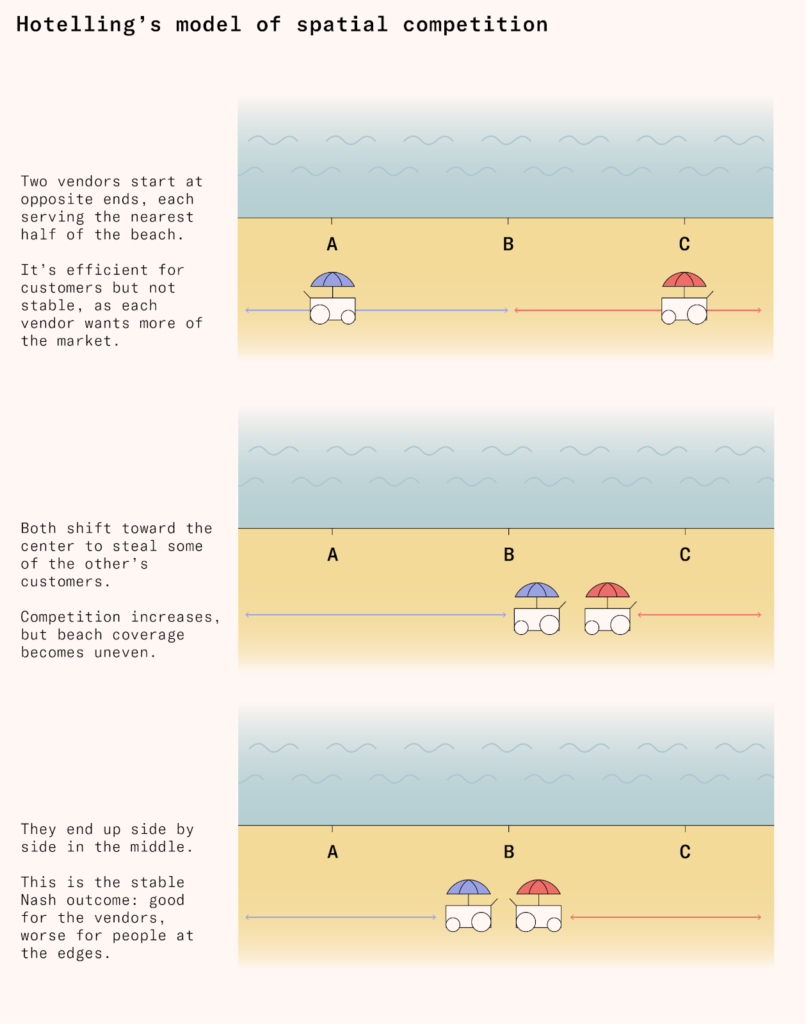

The other regulatory challenge for transport infrastructure arises from a market failure called Hotelling’s Law, named after the economist Harold Hotelling. Imagine a beach on which holidaymakers are evenly distributed. Social value would be maximized by placing the two ice cream vans at points A and C, minimizing the distances that holidaymakers have to walk to them. But in a free market, both ice cream vans have an incentive to edge towards B. The left van will not lose any customers to the left of A by moving rightwards, since it is still closer to them than the right van: it only gains by advancing rightwards and capturing market share from the right van. The right van is subject to equivalent incentives, and so, absent external intervention, both will end up next to each other in the middle of the beach.

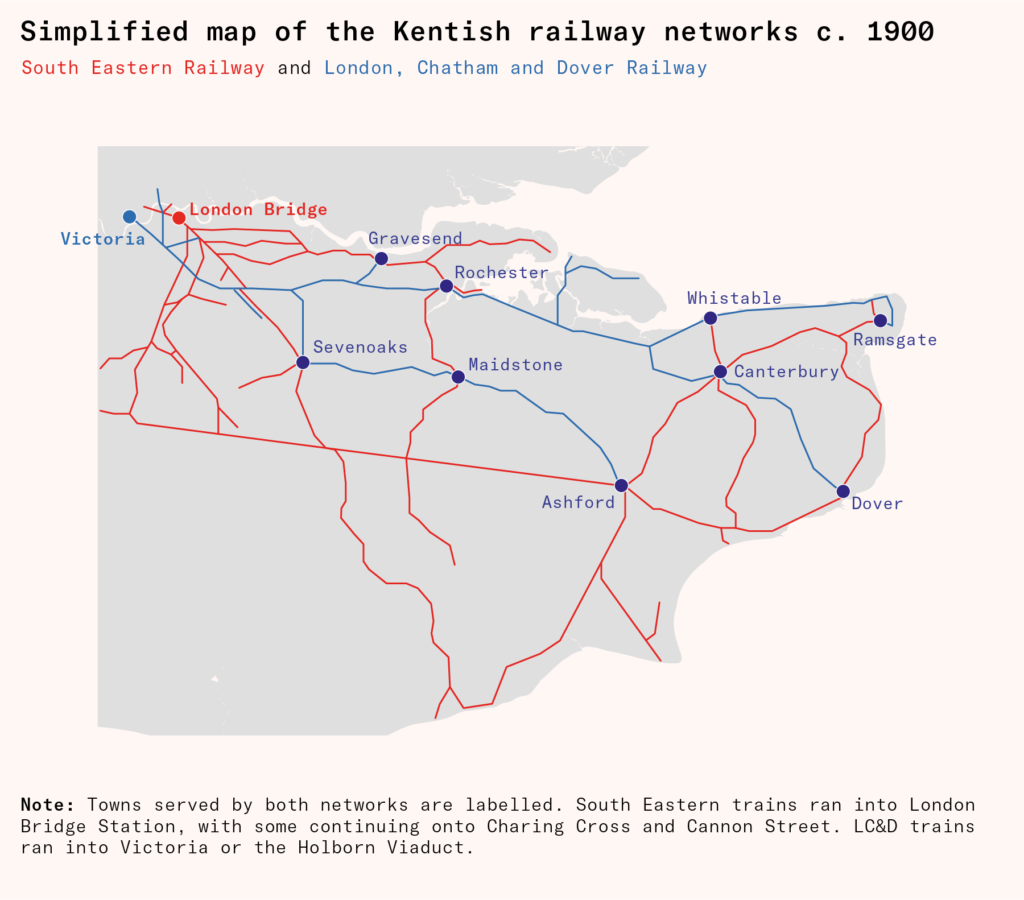

When new kinds of transport infrastructure were invented in the nineteenth century, they tended to be initially unregulated, and Hotelling effects arose swiftly. A classic example is the railways of Kent, developed from the 1840s by two companies, South Eastern Railway (SER) and London, Chatham and Kent Railway (LCKR). The two companies served many of the same suburbs and towns, and some towns ended up with two rival railway stations, giving access to distinct but largely duplicative networks. Vast quantities of capital were thus basically wasted. The two debt-ridden companies eventually merged in 1899, but because of the political difficulties of replanning railway alignments retroactively, southeast London and Kent have a strange and inefficient railway network down to the present day. A few towns, like Canterbury, even preserve multiple railway stations.

In some cases, duplicative lines had even worse effects. The tendency of bus companies to converge on the same routes led to serious congestion, actually lowering throughput. Bus companies also developed a bad habit of ‘racing’: because the first bus to arrive at a stop got all the waiting passengers, buses were incentivized to hurtle past each other in pursuit of fares. In the London neighborhood of Islington, the local vestry council became so fed up that they offered a cash bounty for any information leading to the capture of a dangerous bus driver. In Paris, horse-drawn bus competition was perceived as a crisis by the 1850s, leading to drastic reforms discussed below.

In the twentieth century, many countries nationalized urban infrastructure and funded it through general taxation. In principle, this could solve both the problems we have identified here: the government could subsidize a higher level of public transport than the market would provide, and it could plan the network so that services were efficiently differentiated. Needless to say, it has also brought its own problems: public subsidies are not always forthcoming, and public management not always efficient. In any case, no country in the nineteenth century adopted it wholesale for any services except roads, parks, and drainage. People were used to extremely low taxes, and the tax burden required to cover the cost of municipal infrastructure was still inconceivable.

Without public funding, nineteenth-century governments were obliged to find an alternative way of preventing these market failures. Governments converged on a similar solution: the creation of monopolies. In some cases, governments simply allowed monopolies to develop. This approach was particularly common in Britain. For example, by the late nineteenth century, a large majority of London’s buses were run by a single company, the (originally French) London General Omnibus Company, while almost all the gas of North London was delivered by a company called the Gas Light and Coke Co. Many kinds of infrastructure are natural monopolies, so the authorities needed only to passively acquiesce in order for a dominant firm to emerge in each market through outcompeting or merging with its rivals.

In most countries, however, the authorities were not content to wait for monopolists to emerge naturally. The process was slow and often involved chaotic bankruptcies, which left an endowment of inefficient duplicative infrastructure like the Kentish railways that could only be rationalized at great cost. Many municipalities thus began to legally restrict each infrastructure market to a single operator.

The formal monopoly system came in three main variants. Under the first variant, known as franchising, the service was completely privately owned, though with municipal regulation of prices and routes (in the case of buses and trams). This was the dominant system in the United States, where it was used for buses, trams, gas, and electricity. For example, virtually all trams in Philadelphia were consolidated under the Philadelphia Rapid Transit Company, while the Boston Elevated Rail Company owned the whole rail system in Boston (not just elevated lines, despite the name). Franchises were usually time-limited: when they ended, municipalities usually renegotiated and renewed them, but they could also buy up the infrastructure or even (theoretically) require that the franchise company tear it up.

Under the second variant, known as a concession, the underlying physical infrastructure belonged to the municipality, but concessionaires were given the right to operate it and collect receipts for a fixed period, again subject to regulations from the municipality. At the end of the concession period the municipality could either renew the concession or grant it to a different concessionaire who offered a better deal. This process was smoother than it was with franchises, since the actual tracks or pipes could simply be handed over to the competitor without having to be bought up.

The concessionaire model was highly developed in France, where it was used for all municipal infrastructure except drainage. Two companies, the Compagnie générale des eaux and the Société lyonnaise des eaux et de l’éclairage, came to dominate the entire sector nationally, operating most of the infrastructure of urban France, and competing to win concessions from municipal governments (both companies still exist, now called Veolia and Suez). The French system was widely emulated, especially in Spain and Italy, and by 1900 the great French concessionaires were already multinational powerhouses, operating municipal infrastructure around the world.

Under the third variant of the monopoly system, the whole service was owned and run by the municipality. This approach was pioneered in the German Empire, where most cities municipalized their infrastructure in the late nineteenth century, replacing earlier franchises or concessions. For example, Frankfurt’s gas system was originally established by an English company but municipalized in the 1860s, while its trams were originally private concessions until they were municipalized in the 1890s. All these services were then unified under companies called Stadtwerke. The Stadtwerk model was seen as very successful, and other countries emulated it, including Britain and Austria-Hungary. This process was slow, however: when British utilities were finally nationalized in the 1940s, about half were still in private hands.

These three approaches may sound completely different. But they had some crucial similarities. In all of them, competitors were excluded, services were municipally regulated, and municipal services were normally funded through user fees. With marginal exceptions, the franchise companies and concessionaires received no public money, covering running costs and depreciation through user fees and ideally turning a profit for shareholders to boot. The Metropolitan Street Railway Company, which ran Manhattan’s trams, paid a seven percent dividend in the first decade of the twentieth century, while the Brooklyn Manhattan Transport Corporation, which ran Brooklyn and Queens’s trams, turned a profit of up to $5 million annually, fantastically large by the standards of the time.

More strikingly still, infrastructure companies usually aimed to turn a profit even when they were municipally owned. Many Stadtwerke in Germany and municipal works in Britain were highly profitable, paying for improvements in other public services or cuts to local tax rates. The lucrativeness of municipal works was often explicitly cited as a reason for establishing them. Municipal works were thus run surprisingly similarly to franchises and concessions, essentially as profit-making monopolies whose shareholders were local taxpayers. Nineteenth-century municipalities were almost never bailed out by national governments if they went bankrupt, meaning that they had incentives to avoid profligacy and risk that were similar to those of a private company.

All versions of the monopoly system solved the Hotelling problem: since a single organization controlled the entire network, it was incentivized to space out its services efficiently, rather than cannibalizing customers from its own existing services when it added a new one. They partly corrected for spillover effects. Protection from competition meant that infrastructure operators could charge higher fares, which meant that more lines were viable. Most municipal governments supported infrastructure fervently, so although they capped prices when they allowed monopolies or granted franchises and concessions, they were generally careful to cap them high enough that they did not disincentivize the investment.

The downside of this system, of course, was that higher fares depressed ridership. The overall effect was that cities got more infrastructure, but used it less intensively. This effect was, however, only temporary: when the franchises or concessions came up for renewal, and after the debts from installation (‘undertaking debt’) had been paid off, the municipality could lower fare caps so that fares merely covered operating costs. The standard pattern was thus that new infrastructure was expensive for users for ten or twenty years while the monopolist paid off undertaking debt, before becoming more widely affordable.

For example, in 1899 the authorities determined that Boston’s gas companies had paid off their undertaking debt sufficiently that their maximum prices were lowered to $1.30 per 1,000 feet. Cleveland’s tram franchise had a more sophisticated mechanism written into it so that fares automatically fell when undertaking debt was paid off. Glasgow finished paying off undertaking debt from its trams in the 1910s and steadily cut fares thereafter. Similar examples are found all over the world.

Needless to say, infrastructure companies lobbied to keep prices high as long as possible, and their methods were not always models of transparency. In the United States, nineteenth-century local government was prone to corruption, and infrastructure companies sometimes bribed local politicians to secure more generous franchises.

The most famous practitioner of this was Charles Yerkes, who developed Chicago’s enormous tram system in the 1880s and 90s, despite having previously been jailed twice for larceny and blackmail. Yerkes gave Chicago the greatest tram system in the world, but he did not do so in an idealistic spirit, once remarking that ‘my chief aim in life has been self-satisfaction’. In 1897, a heavily bribed Illinois legislature granted him an exceptionally generous franchise renewal, and the Chicago authorities were about to do the same. The outraged Chicagoans rioted outside City Hall, and the alarmed councillors changed their minds at the last moment. Yerkes indignantly sold off his Chicago assets and moved to London instead, where he founded the Bakerloo, Piccadilly, and Northern Lines. Perhaps rather appropriately, an impact crater on the Moon was later named after this remarkable man.

In fixing sustainable prices, nineteenth-century regulators had one huge advantage over their successors today, which was that there was no inflation. Governments find it extremely difficult to uprate price controls in line with inflation, partly because doing so involves incurring renewed political pain year after year, and partly because imperfect public understanding of economics means that people interpret nominal price increases as real ones. This creates a widespread tendency for controlled prices to rise at below the rate of inflation, resulting in real terms price cuts. Egyptian bread and English university fees are famous examples of this.

Nineteenth-century governments did not face this problem. Provided municipalities set a reasonable price when the concession or franchise was granted, it would remain moderately profitable indefinitely, and might even become more profitable with productivity improvements. All this changed in 1914 when inflation recommenced, rapidly driving down the real value of user fees. By the 1920s, most public transport companies were on the edge of ruin. Utilities were so obviously essential that most governments ultimately grasped the nettle of increasing prices in line with inflation, but most public transport systems remained in financial crisis throughout the interwar period, and were in a position of profound weakness just when competition from cars became intense.

By the 1960s, public transport had collapsed, except where systems were established to subsidize it. The reason why trams survived in Germany while vanishing in Britain, France, and North America was that German trams were run by unified Stadtwerke, which were able to subsidize them from still-profitable utilities services.

The regulated monopoly system had its problems, and the politics of inflation may make it irrecoverable today. But its appeal is apparent given the number of valuable contemporary infrastructure projects that fail to happen because the government is unwilling to subsidize them. For example, there is a strong case for through running some of London’s old suburban railways in a scheme called ‘Crossrail 2’. Despite being widely supported for decades, funding has never been made available, partly because the British government does not like to be seen as favoring London. If fares were decontrolled on Crossrail 2, it is possible that London’s transport operator could fund it from projected fare income. But it is politically delicate to charge £12 for travel on one London railway when all the others cost £2.90.

There are occasional modern examples of transport infrastructure funded in the nineteenth-century manner. In postwar France, the concessionaire system was extended to motorways, which are built and operated by concessionaires and funded entirely by tolls. Austrian motorways are publicly owned but funded by borrowing against future toll income, like Stadtwerk infrastructure before 1914. The Channel Tunnel, a rail tunnel between Britain and France, was similarly delivered by a concessionaire at no cost to the British or French publics, with its cost covered by borrowing against future fare income.

These exceptions may have been possible because they felt so unlike existing transport infrastructure that standard political norms were not applied to them. But it is interesting to consider what other opportunities there might be for more such self-funding infrastructure projects, even under trickier modern conditions.

Buildings

Nineteenth-century governments were not really laissez-faire in their approach to infrastructure, but they were closer to being so with individual buildings. In general, the right of landowners to build on their land was seen as axiomatic. There were limited exceptions. Public authorities reserved the right to ban development on the alignments of future roads. They sometimes banned development around fortresses or city walls to preserve a field of fire for the defenders. For example, Paris was fortified until the 1920s, and development was theoretically banned in a 250-meter-deep area around the walls (in practice the area, known as ‘the Zone’, rapidly filled with slums, only sporadically demolished by the authorities). But only overriding reasons of public good could justify revoking the right to build that citizens enjoyed. In German-speaking Europe, Baufreiheit (‘freedom of building’) was regarded as an important principle of political liberalism; in the English-speaking countries, it was simply taken for granted.

The authorities had somewhat more to say on what people could build. All cities had building regulations, which covered structural soundness and fire safety. In Europe, these rules were fairly strict, usually banning timber from the facade and requiring unbroken masonry party walls between plots. It is because of these rules that a small majority of the fabric of German cities survived the Second World War, while the timber cities of Japan were completely annihilated by firebombing. Similar rules also applied in some American cities, resulting in the development of famous house types like the New York ‘brownstone’. Where fire-proofing rules were laxer, catastrophic fires remained a real risk, as Chicago found to its cost in 1871 and San Francisco in 1906.

In some cases, building regulations included height limits, which were thought to help in fighting fires, preserving light and air for the public realm, and enhancing the cityscape. The maximum height usually varied based on factors like street width, but the usual effect of the regulations was that Paris capped heights at about eight storeys, Berlin at about five, Vienna at about six, and Rome at about six. These limits were usually rigorously enforced and were often the binding constraint on urban density in central areas. In Berlin, for example, virtually every plot was built up to the five-storey limit. Crucially, however, the height limits did not vary from neighborhood to neighborhood: the same limit applied across an entire jurisdiction. Since almost no municipalities were prepared to ban mid-rise in central areas, this meant that mid-rise had to be permitted everywhere, meaning in turn that suburban densification and relatively dense greenfield development were always possible. This began to change only in the 1890s with the emergence of differential area zoning in Germany.

Height limits were much less important in English-speaking countries. Most American cities had none at all, leading to skyscraper downtowns after the invention of steel frames and electric elevators in the 1880s. British municipalities imposed height limits only at the end of the nineteenth century in response to the invention of skyscrapers, usually capping heights at about ten storeys. This blocked some interesting Gothic skyscrapers, but as British cities were almost entirely developed at below ten storeys anyway, the limits were generally not a binding constraint.

Municipalities also regulated plot coverage, though these rules tended to be minimal. Berlin courtyards had to be 5.3 by 5.3 meters, this size being determined by the turning circle of contemporary fire engines. In London, all buildings had to be under a 63.5 degree light plane from the back of the plot, effectively generating a shallow rear setback. Most British municipalities also introduced bylaws governing the layout of working class housing, generally requiring that they have a backyard rather than being built flush with the rear plot boundary. These rules were thought to prevent disease, which was believed to be transmitted through bad air called miasma. Although the miasma theory was scientifically discredited by 1880, it seems to have had a long half-life in the culture of town planning.

Among the most notorious high densities were in the tenements of Manhattan. Until 1867, New York had no coverage restrictions at all. This sometimes resulted in city blocks being completely covered with buildings, the inner rooms of which wholly lacked natural light. In 1867 the city introduced a rule that every room have a window, which builders gamed by introducing dummy windows between rooms while continuing to cover whole city blocks. From 1879, the authorities required that all habitable rooms have a window onto the outside. Builders satisfied this by introducing comically narrow slits between buildings, resulting in the infamous dumbbell plan. Many of these unappealing buildings survive in Lower Manhattan, where, by a curious irony, they now have some of the highest floorspace values on earth. More stringent rules were introduced only in 1901.

Even the most determined friend of urban density today is likely to quail a little before these designs. As contemporary observers pointed out, however, banning them did not necessarily help their residents: in fact, prohibiting the cheapest forms of housing often meant that those who lived in them ended up with nothing at all. Nineteenth-century municipalities were sensitive to this argument, and their building regulations tended to lag behind improvements in market housing generated by rising incomes, except inasmuch as structural soundness and fire risk were concerned.

Today, most cities zone their neighborhoods by use class, finely specifying the activities that can take place there. This happened to a modest extent even in the nineteenth century, with local governments excluding noxious uses from densely populated areas. Slaughterhouses were widely regarded as repulsive neighbors, and it was common for local governments to require them to move to uninhabited areas, along with brick kilns and tanneries.

In general, however, the authorities were extremely liberal about how buildings were used. American permissiveness could reach extremes that even the most radical zoning reformists would probably balk at today. In California, it was not unknown for one’s neighbors to sell their plot to oil prospectors, who would then begin drilling in the next door garden. If they got lucky, a huge plume of oil would burst from the earth, and the whole neighborhood would degenerate into a smoldering hellscape.

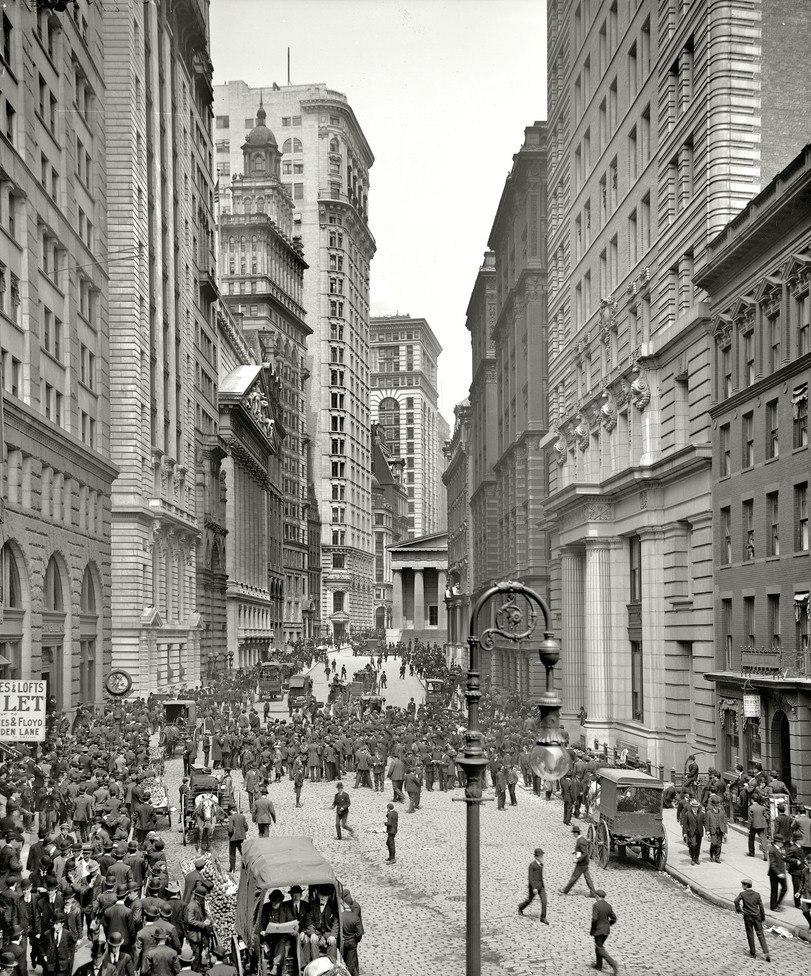

This is rather a special case. But flexibility of use certainly led to change in nineteenth-century cities that use zoning would prevent today. The most striking example of this is the development of central business districts. The development of radial public transit meant that central areas became extremely valuable for commercial and retail uses: the area where the transport lines converged was accessible to the population of a huge area, meaning businesses sited there could draw on larger pools of potential employees or consumers than ever before. Floorspace thus became more valuable in commercial and retail uses than residential ones, leading to the displacement of most residents from urban cores. The City of London, the medieval core of the city, lost three quarters of its residential population between 1850 and 1900. Manhattan’s population peaked in 1910.

This may inspire memories of postwar urban decline, when soaring crime, congestion and deindustrialization led to the collapse of many Anglophone city centers. But the similarity is only superficial. The value and density of floorspace in nineteenth-century centers was rising, not falling. Pedestrians flowed into them every morning; dense and affluent residential neighborhoods clustered around them, like the Upper East Side and the West End. Residential populations declined because mass transit made urban cores even more attractive for something else, not because they had become unattractive places.

This permissiveness created restless cities, in which rapid unwelcome change in a neighborhood’s physical and social character was a constant threat. Nineteenth-century people were anxious about this, and sought ways of mitigating it. Many middle-class people were willing to pay a premium to live in privately covenanted areas, whose developers had imposed rules that would theoretically fix the neighborhood’s character in perpetuity, prohibiting densification, change of use, subletting and subdivision. These restrictions were not very effective. But they suggest that nineteenth-century governments were offering a level of development management below what would have been economically value-maximizing: the addition of restrictions sometimes made neighborhoods more valuable, not less.

On the other hand, the permissiveness of development controls enabled a huge increase in the housing stock. Economic theory predicts that if the supply of housing is unrestricted, the price of housing will not exceed the price of agricultural land plus the cost of building housing on it for any length of time: whenever house prices do rise above the price of agricultural land plus build costs, agricultural landowners will be incentivized to build housing until its price falls back to this point again. Increases in housing demand will thus translate smoothly into increases in housing stock, not increases in price.

The empirical evidence from the nineteenth century confirms this hypothesis. Despite the enormous increase in demand for urban housing caused by demographic and economic growth, real house prices remained roughly flat throughout the period. This is despite the average home becoming considerably larger and better built in the course of the century. In 1800, the median Briton or American was living in a home with two rooms shared with five other people. This began improving around 1850, and by 1914, they were living in a home with four or five rooms and a back yard, shared with three or four other people. Continental housing was worse but also rapidly improving. Anglo-American homes in 1914 were also far more likely to have a garden, and, as we have seen, homes in all countries were far more likely to be connected to running water and gas.

The upshot of this is that the price per square meter of floorspace, let alone per ‘unit of quality’, actually fell. This is because the factors of production got cheaper: agricultural land values remained constant or fell gently due to competition from Ukraine and the New World, while build costs fell due to technological improvements in manufacturing, like the factory production of bricks, joinery, and ornament.

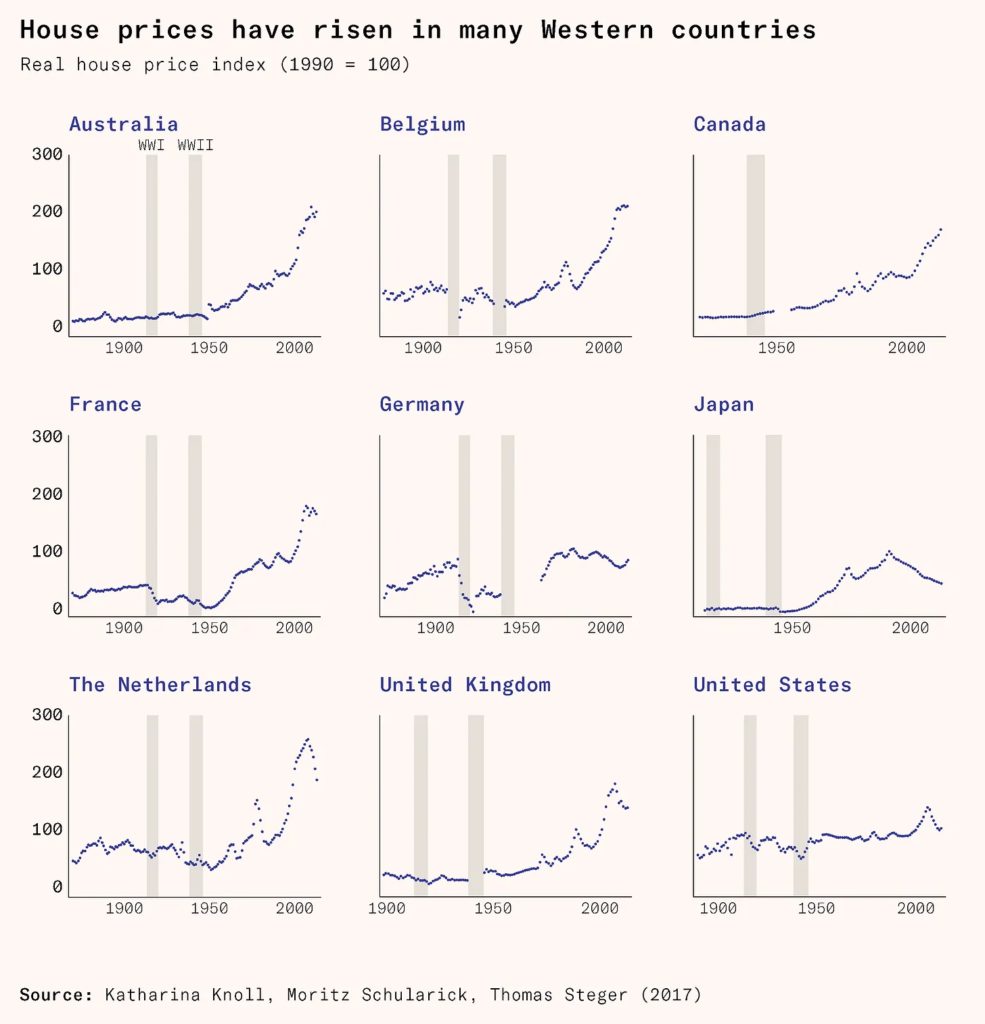

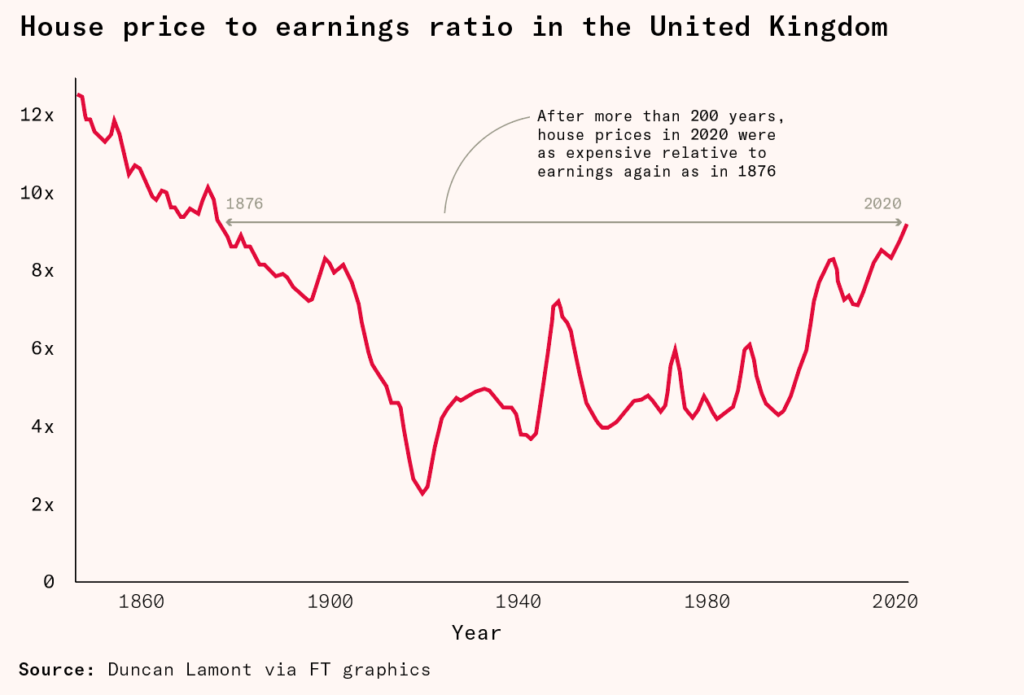

At the same time, incomes rose rapidly, especially after 1850, meaning that housing became dramatically more affordable overall. In Britain, for example, the average house price fell from about twelve times average earnings in 1850 to about four times in 1914. The same trend is evident across the West. Of course, incomes were still very low in 1914, and many Europeans (and to a lesser extent Americans) still lived in terrible housing poverty. But the number was rapidly shrinking. For the first time in history, hundreds of millions of people had escaped from squalor, even as they had escaped from hunger.

In the postwar period, house prices began rising in Europe, Canada and Australia. By far the most important driver of this, generally explaining 80 percent of the total increase, were restrictions on building imposed by public authorities. For many decades, the United States was basically an exception to this trend due to its continued permissiveness towards outward suburban expansion. But since 1990, it too has joined the general upwards trend, especially in major cities.

This rise is so steep that affordability has declined in many major cities, despite rising incomes. In Britain, the average house price started rising again around 1990 and reached nine times average earnings in 2020, the same as it was in 1876. Britain is distinctively bad, but deteriorating affordability is also apparent in Canada, Australia, France, parts of the United States, and many other developed countries. This is strong evidence that, though the optimal level of development control is probably higher than that which prevailed in the nineteenth century, it is far lower than that which has strangulated the housing supply of many cities in the twentieth.

I have argued here that many of the merits of nineteenth-century cities are attributable to their regulatory systems. Some readers may wonder if this is also true of their beauty, the feature that sets them apart so sharply from growing cities around the world today. To the extent that beauty is constituted by good transport, street networks, and so on, a positive answer follows from what has already been said. But to the extent that we are concerned with the visual beauty of their buildings, the answer, perhaps surprisingly, is no.

Nineteenth-century building codes did govern many features that are relevant to a building’s beauty, such as alignment and height. They frequently banned wood from facades as an anti-fire measure, and required various refinements like parapets, raised party walls, and setback windows for the same reason. But it is just not true that they regulated buildings tightly enough to ensure they were beautiful. Nineteenth-century codes almost never required ornament, beautiful materials, or good proportions. It would have been perfectly possible to build an ugly building that complied with them.

A number of myths have arisen in this connection that it is worth exorcizing explicitly. It is often said that the architectural style of Paris was tightly controlled by the government official Baron Haussmann. This is basically untrue. Parisian building codes were silent on architectural style: the authorities did choose a style for the small minority of streets that they compulsorily purchased and redeveloped, but acting in their capacity as a landowner, not as a regulator. Similarly, it is sometimes thought that the four ‘rates’ of London houses corresponded to four state-mandated designs. This too is a misunderstanding. London’s building rules did indeed distinguish four rates of house based on size and sales value, to which different construction standards were applied. However, these standards had nothing at all to say about facade pattern or ornament. Like all codes of the period, they aimed merely at structural integrity and fire safety.

The conclusion is unavoidable that developers invested in beauty not because of regulatory pressures but because of market ones. To put that differently, nineteenth-century people got beautiful buildings because they wanted them – enough that they were prepared to pay for them, despite their relative poverty. The physical character of a city is a flawed guide to the spirit of its inhabitants: there are any number of material constraints and collective action problems that mediate between the two. But we do learn something about the men and women of the nineteenth century from their cathedral-like railway stations, their palatial office blocks, and their carefully ornamented homes.

The twilight of liberal urbanism

The nineteenth-century system did not completely vanish in 1914. Indeed, it has not completely vanished today. France still runs its utilities on the same concessionaire system it used in 1900, and indeed the same two companies still win most of the concessions. German cities still have successful Stadtwerke, although the public transport services they provide are now heavily subsidized. So far as outward expansion is concerned, many American cities remain basically as permissive today as they were in the nineteenth century.

Nonetheless, the system entered a period of crisis and transformation after 1914. The old self-funding transport systems were decimated by the combination of price controls and inflation, and either collapsed or survived on public subsidies. Densification and change of use were gradually banned by the rise of zoning systems. The outward expansion of cities was increasingly restricted by public spatial policy, with national governments deciding which cities would expand and where they would do so. In many continental countries, private homebuilding was decimated for decades by rent controls.

Traditional accounts of nineteenth-century urban development, both by admirers and detractors, tend to present it as laissez-faire. In this story, nineteenth-century cities were the organic product of private enterprise, while twentieth-century cities arose from a hybrid of private enterprise and public planning. This is incomplete and misleading. As we have seen, streets and drains were mostly publicly provided, and in some countries trams, buses, gas, water, and electricity were too. Building regulation was ubiquitous and generally strictly enforced. Infrastructure might be privately owned, but the state shaped the private sector to ensure integrated planning across cities.

The really important differences might be subtler. If we were to specify one unifying virtue of nineteenth-century urban governance, it would not be laissez-faire, but rather the alignment of private interests and public good. Monopolism was a way of creating bodies for whom the best way to maximize profit was to build infrastructure that also maximized value for the city as a whole. Municipal ownership did not change this, because cities raised their own revenues locally and bore full responsibility for their spending decisions. The right to build was generally restricted only where doing so was necessary to prevent exceptionally negative side-effects. The key features of the system turn out to be more elusive principles like ‘users pay’, ‘suppliers profit’, and ‘spendthrift public bodies go bankrupt’.

In the years since 1914, technological and economic progress has continued and accelerated. For all their problems, most Western economies have grown faster since 1945 than they did between 1850 and 1914. The technology underlying construction, transport and utilities has vastly improved. Despite this, urban growth rates have collapsed, housing affordability has deteriorated, urban design has frayed, and urban mobility has stagnated. In some ways, Western societies have become worse at solving the collective action problems of urban life. Nineteenth-century cities were materially poor and technologically primitive, but their institutions were often flexible, vigorous, and creative. We still have something to learn from them.