The West has been below replacement fertility once before. Then came the Baby Boom. Understanding that boom may help us deal with today’s bust.

In 1800, the average British woman had 4.97 children over the course of her life, about the same amount as the average woman living in Burkina Faso today. A century later, Britain’s fertility rate had slipped to 3.9 children per woman. And thirty years later, in 1935, it had plummeted to 1.79, well below the replacement rate of 2.1 – the number of children per woman needed to keep the population steady.

This trend occurred across Europe. By the 1920s, over half of Europeans lived in a country with a below-replacement fertility rate, including Sweden, Germany, and the Czech Republic. The US and Canada also saw steady declines in family sizes throughout the nineteenth century. In 1800, the average American woman had over seven children. By 1900, she had fewer than four, and, by 1930, fewer than three.

Subscribe for $100 to receive six beautiful issues per year.

France’s fertility rate had begun slipping even earlier, to great alarm. In 1896, an organisation called the Alliance nationale pour l’accroissement de la population française was born. Created expressly to combat denatalité – essentially, de-population – it had attracted some 40,000 members by the 1920s with novelist Emile Zola an early recruit. The Alliance nationale was merely one of many organisations, local and national, established to resist France’s apparent progress towards what demographer and statistician Dr Jacques Bertillon despairingly called ‘the imminent disappearance of our country’.

French pronatalists frequently and vividly campaigned on the issue as a serious matter of national security. In 1914, the Alliance nationale published over a million posters showing two Frenchmen being bayoneted by five Germans. The poster bore a caption explaining that for every five German soldiers born, only two French soldiers were.

The French were not the only nation to chafe against a new reality of smaller family sizes and quieter maternity wards. The British government established the National Birth Rate Commission in 1912. In fascist Italy, the ‘Battle for Births’ was named one of Mussolini’s four key economic campaigns in 1922.

Contemporary demographers looked to shifts in values to explain the decline, like rising individualism, new family structures and ways of living that were less compatible with parenthood. Enid Charles, a British statistician and feminist, argued that increased female employment was one cause, because motherhood made it difficult for women to compete with men economically. Charles, a mother of four, called children ‘a handicap to vocational advancement in adult life’.

Despite the organised resistance of groups like Alliance nationale, at least some European demographers doubted whether falling birth rates were truly reversible, or even arrestable. In 1936 Dr Carr Saunders, an English biologist, eugenicist, and later Director of LSE, wrote:

once the small voluntary family habit has gained a foothold, the size of the family is likely, if not certain, in time to become so small that the reproduction rate will fall below replacement rate, and that, when this happened, the restoration of a replacement rate proves to be an exceedingly difficult and obstinate problem.

But even as Carr Saunders wrote those words, he was being proved wrong. Something was happening, in Europe and farther afield. Something we are still trying to understand today: the Baby Boom.

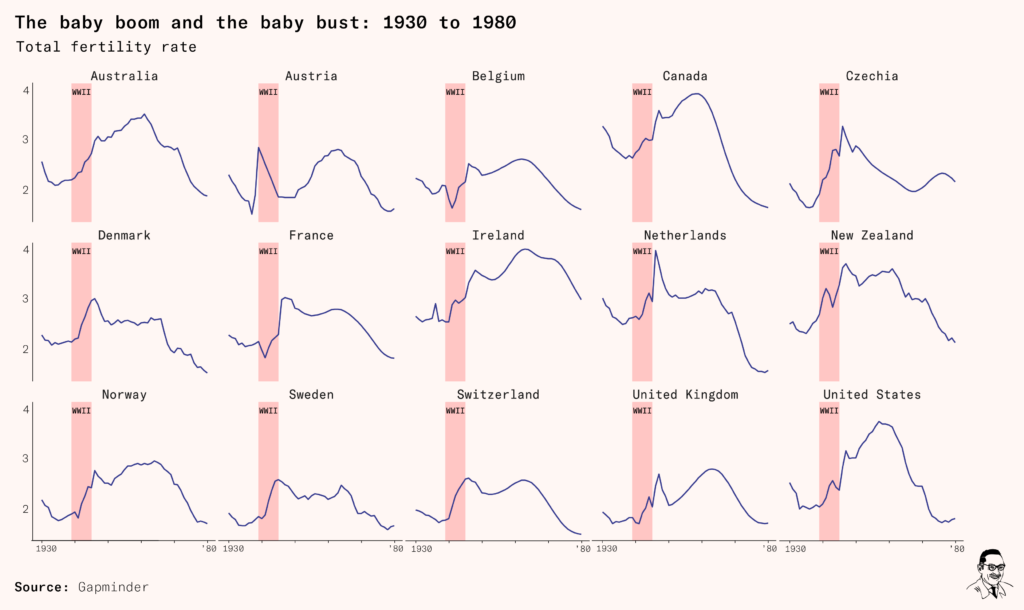

The Baby Boom was an unexpected change in direction from the century of falling fertility that had taken place in Europe and North America. Contrary to the popular belief that it was triggered by soldiers returning home from World War Two, the Boom in fact began in the mid-1930s. It was not simply an American or British phenomenon either. The demographic wave swept over Iceland, Poland, Sweden, France, the Netherlands, Austria, the Czech Republic, Canada, Norway, Switzerland, and Finland. Thousands of miles across the sea, it even happened in Australia and New Zealand.

And yet Carr Saunders’ doubt had been extremely well justified.

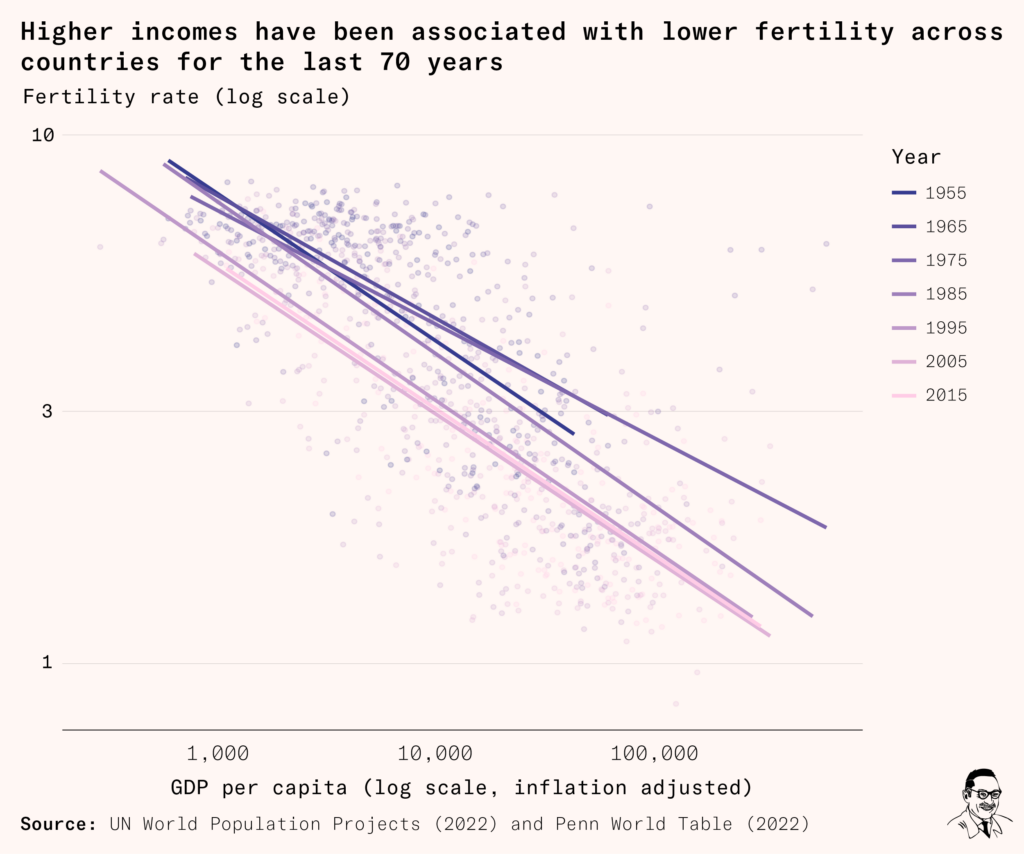

For wherever and whenever we have had data and since the Industrial Revolution – with the crucial exception of the Baby Boom – it has been a nearly iron law of fertility that higher incomes are associated with lower birth rates. A key mechanism for this is likely to be that rising living standards effectively increase the costs of having a child, from lost wages for working women to reduced time for increasingly accessible leisure activities.

This is shown clearly in the chart of income and fertility since the Second World War above, with the depressive effect of rising incomes on fertility strongest for increases at the lower end of the income scale, as can be seen by the rapid drop in fertility in the left part of the above chart.

We even see the strong negative association between higher incomes and lower birth rates in American census data that stretches all the way back to those born in 1828: as the chart above shows, better-paid occupations tend to have fewer children in each birth cohort. And as generations get paid more over time, they have fewer children too.

And yet there was something different about the parents of the generation we now refer to as baby boomers. Though they were still affected by the inverse relationship between higher income and lower births, they were much likelier to have children – and more of them – than those born before or after them. Why?

The Baby Boom: what happened?

There were more babies born in 1947 than in any year for the last quarter of a century. For six years the birth-rate has been going up and up. Now there is a great question mark – will the baby boom continue in 1948?

Charles Rowe, The People, Sunday 28 December 1947

In the countries that it touched, the Baby Boom created generations massive in size. In the US alone, 76 million babies were born in its peak 18 years, 30 million more than were born in the previous 18, a demographic difference bigger than the 1960 population of Egypt, the Philippines, or Ethiopia. By 1965, people born during the Baby Boom made up 40 percent of America’s population.

Today, a fifth of both the UK’s and the USA’s population are baby boomers and we live in the world they created. Despite that, as mentioned above, the most widely known piece of information about the Boom is its most pervasive myth, that it was caused by the end of World War Two.

The Baby Boom was not the result of people making up for lost time during the war: it saw total lifetime fertility rates rise, meaning that people did not simply shift when they had their children but had more of them overall. And in many countries, including the US, UK, Sweden and France, the rise in birth rates began years before the war had even started, while neutral Ireland and Switzerland experienced Booms that began during the war, in 1940.

Instead, to explain the Baby Boom, we must consider why it was that the iron law of fertility – that as incomes go up, births must come down – was suspended for this extraordinary period of time. Since the Baby Boom, one hypothesis has dominated the academic debate.

The Easterlin Hypothesis

It took over a quarter of a century after the Baby Boom began for the first substantive theory attempting to explain it to arrive, from economist Richard Easterlin in 1961 – what we will refer to as the Easterlin Hypothesis. Even today, perhaps because of its intuitive elegance, the Easterlin Hypothesis continues to attract credibility despite weak evidence in its favour and the emergence of more robust theories.

Easterlin’s explanation rests on the idea that the decisions individuals make in terms of whether and how many children they will have are strongly influenced by the difference between what they had expected their adult income to be while growing up, their ‘expected income’, and what it actually is once they join the labour market, which he called ‘relative income’. He argued that people form an expectation of their income based on a range of social and economic signals, primarily those they receive growing up: the current average standard of living; the standard of living they experienced during their childhood; their sense of their own prospects.

The childhoods of the parents of the baby boomers were marked by the Great Depression, during which unemployment rose to 25 percent and 9,000 US banks collapsed, taking people’s savings with them. The US downturn was felt around the world: US GDP fell by 29 percent between 1929 and 1933, and global GDP by an estimated 15 percent. It was only around the end of the 1930s and the onset of the Second World War that economic growth began to pick up.

The children of the Dust Bowl found themselves adults in a sunnier, greener world than they had expected and they embraced it, getting married and having children earlier than their parents had, or than they likely would have if the economic recovery had been more subdued. It is this rise in relative income, compared with what they might have expected, that Easterlin suggested caused the Baby Boom.

Easterlin also argued that the same factors that caused the Boom caused its demise, because baby boomers grew up with more peers with whom they had to compete with for jobs. Easterlin predicted this meant that, unlike their parents, baby boomers ended up with incomes lower than they might have expected to earn, causing them to marry later and have smaller families. He thought this would create a cycle: the next generation would have fewer peers to compete with, enter a more favourable labour market, and so have their income expectations exceeded – if they based their expectation on their parents’ labour market experiences. Easterlin thought understanding this cycle would allow the prediction of regular baby booms and busts.

In 1978 Easterlin used this cyclical element of his theory to predict that another baby boom would hit the West in the mid-1980s. But it never did. Instead, American fertility rose from 1.83 in 1980 to 2.07 in 1990, and then fell: a far cry from the demographic wave of the Baby Boom, in which fertility rose by over 75 percent in many cases. Meanwhile in Europe, fertility largely flat-lined or declined. The cycle that is at the heart of the theory never emerged, and little trace of it can be seen in the decades that preceded the Baby Boom.

But, more damningly for the Easterlin Hypothesis, despite dozens of studies and meta-studies spanning more than fifty years, knockdown statistical evidence for the theory – i.e. indisputable correlations between some measure of Easterlin’s ‘relative income’, and fertility – is elusive and the academic debate that surrounds it remains unsettled. Lack of academic consensus is driven in large part by the fact that the key variable at the core of the theory – relative income – has been defined in a multitude of ways.

When Easterlin first proposed his hypothesis, he analysed relative income in terms of the ratio between the number of men in the population starting their careers and the number of men at a later stage of their career, measured as the number of men aged 15 to 29, compared with those aged 30 to 64. Easterlin thought this measure, in revealing the competitiveness of the labour market over time, could act as a proxy for relative income.

Other authors iterated on Easterlin’s original measurement of relative income in many ways, picking different age bands, for example comparing those aged 20 to 22 with those 45 to 49, or those aged 18 to 24 with those aged 25 to 64, or those aged 15 to 34 with those aged 35 to 64. Others chose to use wage ratios as a proxy for relative income instead, comparing the average wages of a younger age group with that that older cohorts would have earned when starting their careers. A debate continues as to whether the groups analysed should be male-only, as in Easterlin’s original paper, or both. Easterlin himself has investigated his own hypothesis with a variety of different measurements.

This smorgasbord of measurement techniques might make it easier for researchers to find a statistically significant result, but ultimately does not get us much closer to the truth, with many studies that find a significant relationship between relative income and fertility, and many that do not.

Even the strongest research showing a robust relationship between relative income and fertility finds that at best it can only explain a small fraction, such as 12%, of the rise in fertility during the Baby Boom, reinforcing that other factors were at play. With no consensus on what the right measure for relative income is, Easterlin’s Hypothesis is functionally unfalsifiable. Impossible to disprove, but lacking decisive evidence that would show it to be the definitive explanation of the Baby Boom, this zombie theory shambles on.

Easterlin focused on parents’ perceptions and expectations in his attempt to understand what drove the Boom. A recent wave of research has looked instead to objective factors – in particular the costs of having children upon parents and how these changed. .

The Parenting Cost Shock: easier, safer, and cheaper

Parenthood rapidly became much easier and safer between the 1930s and 1950s. The spread of labour-saving devices in the home such as washing machines and fridges made raising children easier; improvements in medicine making childbirth safer; and easier access to housing made it cheaper to house larger families.

In 1930, only two thirds of US homes had electricity. By 1960, 99 percent did. The UK and other European countries saw similar rollout rates. This household electrification paved the way for other technologies, including home refrigeration which became more popular after the introduction of a compound called Freon in the 1920s, a safer alternative to toxic chemicals previously used in fridges. Between 1930 and 1950, the share of American households with a refrigerator increased from 10 to 80 percent.

This allowed consumers to take advantage of other innovations. In 1928, Birds Eye developed the double belt freezer which allowed rapid freezing of fresh produce, improving the quality of frozen food. With refrigerators found in an increasing number of homes, frozen food became popular from the 1930s onwards, followed by frozen ready meals: in 1946, the UK’s frozen food sales amounted to only £150,000, but by 1964 that had grown to £75 million (about £1 billion in 2020s money).

Other labour-saving technologies proliferated and transformed the lives of ordinary people, particularly women. Consider the washing machine. Before this revolutionary object became a feature of daily life, doing the laundry meant heating water with coal or firewood and scrubbing every item by hand.

This was hot, sweaty work, often including pounding the laundry in a tub with something called a ‘washing dolly’, and its strenuous nature meant that women generally scheduled the chore for a Monday, as it followed Sunday’s day of rest. One early washing machine advert explicitly promised to ‘transform Blue Monday into a bright and happy day’. By the 1940s, electric washing machines were becoming normal in middle class homes.

Before electrification and the emergence of these innovative household gadgets, we can easily imagine how heavy the burden of domestic life weighed on parents’ shoulders. These burdens might have discouraged larger families and the calloused hands and weary joints such a prospect entailed. After all, another smiling baby meant more time spent peeling potatoes and more dirty clothes to pound clean.

To test this intuition, a 2005 paper from economists Jeremy Greenwood, Ananth Seshadri and Guillaume Vandenbroucke built a simplified economic model of American fertility. In this model, fertility is primarily affected by two factors: income and technological growth in household products. This simplified model is pretty good at predicting fertility over the period – including the Baby Boom. If a simple model predicts something well, that suggests that the factors in the model could be associated with the outcome – in this case, it suggests that household technologies (like washing machines and fridges) were able to push back against the declines induced by continually rising income.

In 2009, a new paper highlighted the extent to which this single factor, advancements in household technology, is not able to independently explain the Baby Boom. The paper offered an experimental test of household technology’s effect on birth rates by examining the experience during the Baby Boom of the American Amish, an Anabaptist Christian community that, famously, shuns much modern technology.

While there is some variation between groups, electricity, central heating, cars and telephones are nearly universally shunned by Amish people. For many Amish, the list of prohibited items extends to zips, velcro and even buttons.

If improvements in household technology were the main driver behind the Baby Boom, we would expect the Amish not to have experienced a boom themselves. But they did.

Historical demographic data on practising Amish is scant. But the language Pennsylvania Dutch is spoken almost exclusively by the Amish, and language is recorded in the census. By analysing data from the only US censuses from the relevant time period that included data on primary language spoken in the home and the number of children born – 1940, 1980, and 1990 – it is possible to gauge the impact of the Baby Boom on the Amish community by tracking changes in completed fertility among Pennsylvania Dutch speakers. It turns out that during the Baby Boom Pennsylvania Dutch speakers did see fertility rise at the same time, at a similar magnitude to other Americans, and for as long – all without washing machines and refrigerators. On this basis, should we disregard the role of new household technologies in giving us the Boom?

It is undeniable that the progress in these technologies of the thirties, forties and fifties delivered an easier life to millions, including parents. But the fact that the Amish also saw fertility climb shows us that the Baby Boom is at very least multifactorial.

The Amish were insulated from the effects of new household technology in lowering the costs of having children at the time of the Boom. But they, alongside the rest of the West, benefited from another major change that acted similarly to make having children easier: medical innovations that made giving birth far safer.

Between 1936 and 1956, America’s maternal death rate fell by 94 percent, from 51 deaths per 10,000 live births to under 3 deaths per 10,000 births. This was mirrored by declines across the West – Sweden saw maternal deaths fall from 30 per 10,000 to 4 per 10,000 live births in the same period. In England in 1874, maternal mortality peaked at 75 per 10,000 live births. Seventy years on in 1945, it was less than 5.

This maternal mortality collapse came in large part due to the introduction of sulfonamides in the 1930s, one of the first antibiotics. These medicines, and penicillin which arrived soon after, drove down incidences of sepsis (blood infection), responsible for 40 percent of maternal deaths at the time, and made caesarean sections safer.

Public awareness of these changes was high. Penicillin launched into the public consciousness as a ‘wonder drug’ and was entering general medical use across the West by the end of World War Two. In the late 1940s, US funding enabled the establishment of penicillin factories across continental Europe via a predecessor of the World Health Organisation, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Theft of penicillin in post-war Vienna is a key plot point in 1949’s The Third Man, the most popular film in British cinemas that year.

Other medical innovations were also working to make births safer. The first hospital blood bank in America was established in Chicago in 1937 and these services, armed with a recent understanding of blood types and safe transfusions, began to drive down another major cause of maternal mortality, blood loss.

These medical advances, which were being made across the West, radically reduced the most serious potential cost faced by prospective mothers: life itself.

Some US states had much higher maternal mortality than others. For example, averaged between 1915 and 1934, Florida had almost double the maternal death rate of Minnesota, 86 per 10,000 as compared to 44. By the 1950s, death rates had massively converged – and those states with the biggest improvements saw the biggest increases in birth rates.

By comparing state falls in mortality with state baby booms, one analysis shows the effect of these medical advances on fertility in America was 1.08 children per woman, or 58 percent of the rise in fertility seen among baby boomers’ parents.

And what about the Amish?

Unlike cars, washing machines, and buttons, medical technology is not shunned by the American Amish. John A. Hostetler, an anthropologist who was himself born into an Amish family, wrote in 1964:

Scientific concepts of healing generally do not conflict with Amish values. Modern science has penetrated the Amish culture to a far greater extent than have other aspects of the “worldly” culture…they have erected no boundaries against hospital or improved medical care.

We can see this in Amish child mortality rates in Ohio at the time of the Baby Boom which are similar to other rural Ohioan communities.

At this time, advances in medical technology are likely to have had an outsized effect on Amish birth rates. It is the case both before the Boom and today that Amish people have significantly larger families than average Americans. The average American woman born in 1930 had 3 children, while the average Amish woman born in the same year had 4.5. Given that the risk of maternal mortality is higher for first-time mothers, safer birth would have significantly boosted the total number of Amish children born, in comparison with non-Amish, as an Amish woman who might died without advances in medicine were likely to go on to have considerably more children than a non-Amish woman in the same position. This may explain why the Amish experienced the Baby Boom in similar magnitude to non-Amish, despite their limited take up of new household technologies, and underlines why we should not completely dismiss the role of household technology.

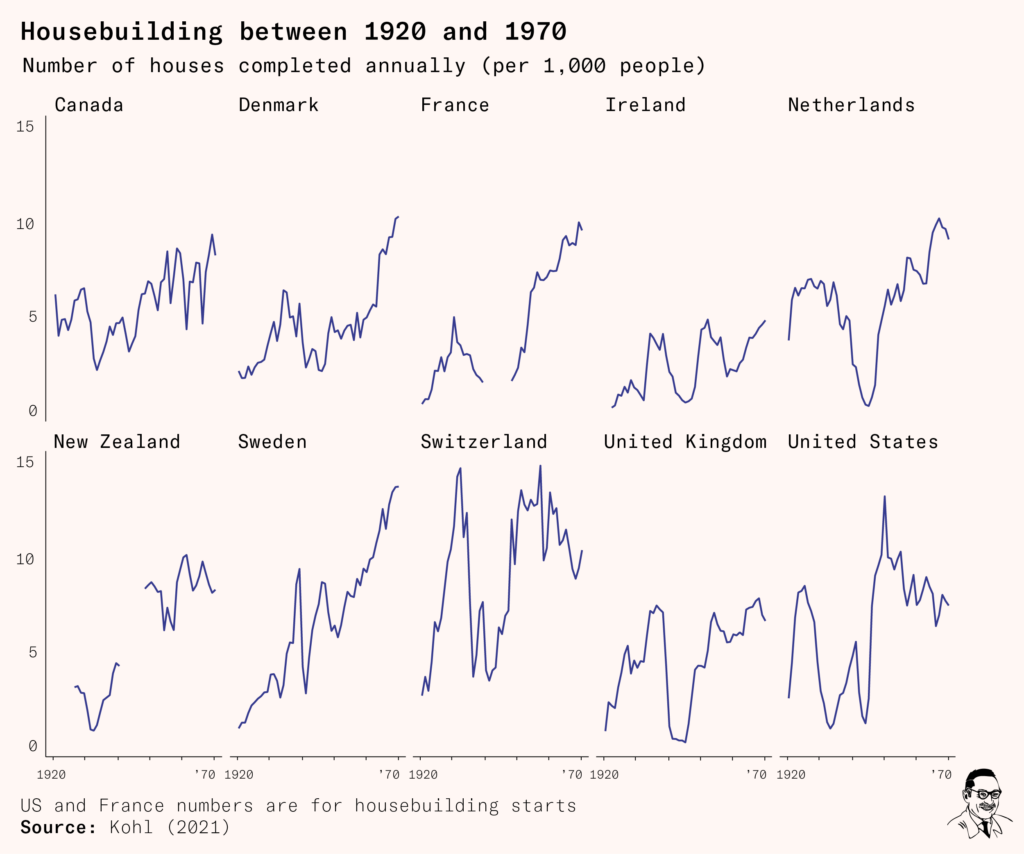

Alongside strides forward in household and medical technology, there is one final factor that acted to lower the costs of having a child and create the Baby Boom: it became easier to secure a home in which to raise children. The number of houses built soared across the West after World War Two, including in New Zealand, Sweden, the US and Switzerland. In the UK, development did not increase immediately after the war, but the rate of housebuilding did remain close to the all-time high it had hit in the 1930s.

This house-building bonanza led to sharp rises in homeownership rates. In 1940, less than 30 percent of American men aged over eighteen were homeowners. By 1960, it was 52 percent. In the UK, rates of homeownership jumped from 32 percent in 1938, just before the war, to just over half by 1967.

There was a strong social expectation that married couples should have their own household: in 1940, 93 percent of married 25 year olds in the US had their own households, while just 44 percent of non-married 25 year olds did. With easier access to the housing that social pressure made necessary, marriage rates rose: between 1930 and 1960, marriage rates in the US increased by 21 percent. Those more likely to marry were in turn more likely to become parents. In this way, the increase in supply of housing fed the Baby Boom.

Another way of demonstrating this is to consider the number of building permits issued across American towns during the Baby Boom period and their effect on marriage rates. As the American house building bonanza unfolded, increasing the number of building permits issued per 100 people by one corresponded to a subsequent increase in marriage rates of 17 percent over the next three years.

Overall, this suggests that the increase in construction – as measured by the number of permits issued to build homes – was responsible for a third of the rise in marriage rates in the US between 1930 and 1950. With married American women much more likely to have children – only 4% of births in 1950 were to unmarried women – around 10% of the overall rise in births during the Baby Boom in America can likely be attributed to increased homeownership.

The rapid rise in housebuilding was not limited to the US: between 1930 and 1960, marriage rates increased across the West, in some cases dramatically, and the average age at first marriage fell. In England and Wales, 26 percent of women aged 20 to 24 were married in 1930; by 1960, 58 percent of women aged 20 to 24 were.

The golden thread linking the phenomena that comprise the triple mechanism we describe above – advances in household technology, progress in medical technology, and easier access to housing – is that they together sharply reduced the cost of having children. Household technologies meant less time was needed to care for children. Medical technology lowered the chance of mortality. Affordable housing lowered the cost of family formation, so people did it earlier and had bigger families. Together, these changes may have been powerful enough to counteract the depressive effect of rising incomes on fertility rates. Even the improvements in medicine, likely the most powerful force, may not have been strong enough to cause the Baby Boom alone.

However, the triple mechanism’s booster effect on birth rates was temporary, as the rate of improvements across these three areas slowed, or even stopped. Their effect was then overwhelmed by the effect of the continuing rise in living standards seen across the West and by the 1970s, most of the West had returned to a pre-Baby Boom state of decline in fertility rates.

Another Baby Boom?

Birth rates have continued to slowly decline since the 1970s. Today, there is no European country with a fertility rate that exceeds replacement rate, with rates as low as 1.3 in Italy and 1.2 in Spain. As it was in the early twentieth century, the West is again in the midst of a demographic winter.

To have a genuine shot at seeing spring again, policy makers should look back at the Baby Boom and how, for a lucky generation, being a parent became an easier and safer choice at breakneck speed.

We do not need a Mussolini-style ‘Battle for Births’ or the mass production of propaganda posters to bring about a demographic thaw. Such measures were not responsible for the Baby Boom, which was delivered by progress and positive changes that meant life-enhancing developments for millions.

If the parenting costs theory of the Baby Boom is right, it suggests that birth rates can be increased by making it safer and easier to choose to have children. Today, the most obvious parallels with the developments that we have argued gave us the Baby Boom are cheaper household appliances that make it easier for parents to raise their children; better and more affordable maternal healthcare and fertility assistance, from more generous IVF policies to artificial wombs; and, cheaper and more plentiful housing for families.

In January 2023, the United Nations published a report which described population ageing as an ‘irreversible trend’, speaking of declining fertility with an inexorability that echoes Dr Carr Saunders’ remarks in 1936. But Carr Saunders was proved wrong by the powerful countervailing effects of progress, and by focussing on material improvements that reduce the costs of having children, we can accomplish the same today.